Excerpt

Excerpt

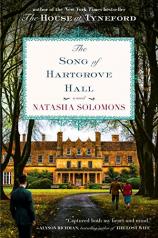

The Song of Hartgrove Hall

March 2000

Edie sang at her own funeral. It couldn’t have been any other way. Most people first knew her by her voice. New acquaintances took a few weeks or months to reconcile that voice, that thrill of sound, with the slight, grey-eyed woman holding the large handbag. She was a garden thrush with the throat of a nightingale. It was one of her nicknames—‘The Little Nightingale’—and the one I felt suited her best. The nightingale isn’t quite who we think she is. Contrary to what most people believe, the nightingale isn’t a British bird who winters in Africa. She’s an African bird who summers in England, and the sought-after music of an English summer evening is really music from the African bush, as native to Guinea-Bissau as to the moss-sprung and anemone-speckled

copses of Berkshire and Dorset.

Edie once told me that the English countryside never really made sense to her. Her tiny Russian grandmother had looked after her while her parents manned their stall in Brick Lane, and she used to tell Edie stories. In winter they’d huddle under blankets beside the electric fire in their grotty flat, passing a cigarette back and forth, Edie listening, her Bubbe talking. Bubbe’s stories were all of Russia and the white cold, a cold so deep it turned your bones to ice, and if the wind blew hard, you’d shatter into a billion pieces, fluttering to the ground as yet more snow.

In summer Edie and Bubbe would take apples out to the scrap of green that passed for a park and sit on a tarpaulin square (for a woman raised in Siberia, Edie’s grandmother was remarkably anxious about the ill effects of dew damp grass). On sun-filled afternoons, when grubby daisies unfurled in the warmth, young men unbuttoned their shirts to the navel and girls furtively unpeeled their stockings, Bubbe would tell stories full of snow. Edie would lie back and close her eyes against the jewel-gleam of the hot sun and envision snow racing across the grass in waves, turning everything white, smothering the sunbathers who had only a moment to shiver and scream before they shattered into ice.

It was rare for Edie to confide anything about her child- hood. She kept it close, self-conscious and uneasy under the barrage of my interest. ‘I’m not like you. It wasn’t like this,’ she’d say, gesturing to the house with its lobes of wisteria or at the trembling willows by the lake. I’d feel embarrassed and overcome with a very British need to apologise for the quiet privilege of my own childhood, which, according to Edie, must have diminished any loss or sadness that dared intrude in such a place.

For all their charm, the gardens at Hartgrove never quite touched Edie. She admired the tumbles of violets, and the slender spring irises the colour of school ink, but she never troubled to learn the names of the flowers. I always had the gardener fill the pots on the terrace where we breakfasted with golden marigolds, so she insisted on calling them the marmalade flowers. It confused Clara sufficiently that, when she was about five, I caught her trying to spread the marmalade flowers on her toast.

But when it snowed , Edie longed to be outdoors. She was more excited than the children. At the first flake, she’d put on three coats at once, bandage her head in coloured scarves like a babushka and rush out, staring at the sky and willing a bliz- zard. Long after the girls were tired and damp from sledging in the fields, Edie lingered. Clara and Lucy would flop before the hearth in my study beside the steaming spaniels, and present to the fire rows of cold pink toes. Under the pretext of putting on a record for the girls (The Nutcracker or a swirling, cinnamon-sprinkled Viennese waltz—our children’s taste in music was as sugar-sweet as the candy they lusted after), from the window I’d watch Edie as she’d start towards the house and then pause every few steps, turning back to gaze at the white hills and the huddle of dark woods, like a lover reluctant to say a last goodbye.

So many people think they knew her. The Little Nightingale. England’s perfect rose. But Edie didn’t dream of roses in summertime, she dreamed of walking through snow, the first footsteps on an icy morning.

November 1946

Hartgrove Hall is ours again. It’s a strange sensation, this supposed homecoming—the prodigal sons returning all at once to Dorset on a bloody cold November morning. We are silent on the drive from the station to the house. Chivers steers the cantankerous Austin at a steady twenty miles per hour, the General parked beside him on the front seat absolutely upright as though off to inspect the troops, while Jack, George and I are jammed into the back, trying not to meet one another’s eyes as we stare resolutely out of the windows.

I’m nervous about seeing her again. Hartgrove Hall is our long-lost love, the pen pal we’ve been mooning over in our thoughts for the last seven years, but each of us is submerged in lonely and silent anxiety at the prospect of our reunion. We know the house has had a tricky war—a parade of British regiments followed by the Americans, all of them tenants with mightier preoccupations than pruning the roses or sweeping the drawing room chimney or halting the onslaught of death-watch beetle that has been gobbling through the rafters forever.

As the car creeps higher and into the shadow of the hill, hoarfrost is draped across the branches like banners and where the trees meet across the narrow lane, we plunge through a tunnel of silver and white. The car turns into the long drive- way and there she is, Hartgrove Hall, bathed in early morning haze. To my relief she’s still the beauty I remember. I can’t see her flaws through the kindly mist, only the buttery warmth of the stone front, the thick limestone slabs on the roof drizzled with yellowing lichen. I climb out of the car and absorb the multitude of high mullioned windows and the elegant slope of the porch, and out of childish habit suddenly recalled, I count the skulk of stone foxes from the family crest that are carved on the flushwork. Ivy half conceals the smallest fox, so that he pokes his snout out from amongst the leaves as if he’s shy. I’m frightfully glad to see him. I thought I’d recalled every detail of the house. I’d paced its walks and corridors each night before falling asleep and yet, already, here is something I’d quite forgotten.

The yellow sandstone façade is the same but the wisteria has been hacked away and without it the front looks naked. All of the windows are unlit and the house looks cold, unready for guests. We’re not guests, I remind myself. We are the family returned. Yet it’s an odd sort of homecoming: instead of Chivers or one of the maids lingering in the porch to welcome us, a major from the Guards waits on the front steps, stamp- ing his feet to keep warm. On seeing us, he stops abruptly and salutes the General. The major thanks him for his honourable sacrifice and generosity even though we all know it’s bunkum and the house was requisitioned by law. Although, I suppose, knowing the General, he would have surrendered the house in any case out of a sense of duty. The General takes great pleas- ure in doing his duty. The more unpleasant the sacrifice, the more he enjoys it.

The major clearly wants to be off but Father keeps him talking outside for a good fifteen minutes while it starts to sleet. We all stand there rigid with cold and boredom. I’m amazed that Jack doesn’t declare, ‘Bugger this, I’m off to inspect the damage done to the old girl,’ and disappear, but then he and George have been demobbed for only a month or so. Beneath the civvy clothes they still possess a soldier’s habits and to walk away from a senior officer wouldn’t just be poor manners but a disciplinary offence.

After an age, the General allows the unfortunate major to depart and marches indoors. Jack, George and I hesitate, unwilling to follow. I want our reunion to be private and, as I glance at my brothers, it is clear that they feel the same. Jack lingers for a moment, then turns back down the steps, making for the river, while George heads in the opposite direction, crossing the lawns towards the lake. I wait for a minute, gulping cold, fresh air, feeling the bite and tang of it on my teeth, and then slip into the house. The great hall is almost as frigid as it is outside. In the vast and soot-stained inglenook there is no fire. I am almost certain that there used to be a constant fire. The requisite carved foxes gaze out from the stone- carved struts, chilly and forlorn. I suppose there is no one to light a fire now and I don’t suppose there will be again. I notice that the mantelpiece is missing. I can’t think how it was taken or why.

The walls are bereft of paintings. The good ones haven’t hung here for years. They were flogged, one Gainsborough and Stubbs at a time, but my ancestors were sentimental chaps. Until the army requisitioned the house, copies of the originals used to hang around the hall—gloomy reminders of what was lost to Christie’s to pay inheritance tax, veterinarian bills, servants’ wages and to replace rotting windows. Some of the copies were rather good, others less so—peculiar, carnival-mirror distortions of the originals. For years, Jack, George and I used to play ‘spot the imposter’ and attempt to guess which of the bewigged and unsmiling portraits were copies. Then the General told us that none of them was real and the game was rendered pointless.

The last painting to go was a dear Constable landscape of the woodland beneath Hartgrove barrow. The painter stands at the top of the ridge, gazing down at a brown wood dabbed with autumn light. Somewhere in the painting a nightingale sings—the last of the year. The copy of the Constable is quite decent. I’ve always liked it, even though the colours are second rate and the lines muddy—but I can still hear the nightingale and that’s what matters. George sent it to me, along with his letter explaining that the house was to be requisitioned. I’d been alone at school when the news had come, and it had left me disconsolate. Only George would have thought to send the painting with the horrid news—a kind memento of home to sustain me. Inevitably the painted view began to supplant the one in my imagination until I began to see the barrow and woods third hand—Constable’s vision re-daubed by a copyist.

I return to the car, retrieve the picture from the boot and rehang it on a nail in the hall. It looks lost and small.

I’m chilled and feel queasy from the pervasive stench of damp. Disheartened, I retreat down the steps and out across the tangle of gardens before striking uphill towards the ridge of Hartgrove barrow. I set off at a lick until, breathless from exertion, I pause at the first of the grass terraces rippling the hillside to look down at the house. It’s different for me than for the others. I was eleven when she was taken in ’39 and I don’t remember how she’s supposed to be, not with the absolute clarity of Jack or George. From my vantage point I can see the burned-out south wing. An accident with an ember smouldering in an unswept chimney, according to the letter sent by the War Office, although Jack heard rumours it was a game gone awry in the Officers’ Mess. They’d been bottling farts into brandy bottles—such an ignominious end for four hundred years of history: sent up in smoke by a lit fart.

I’m not surprised no one could face confessing the truth to the General. I spent much of the war evading him myself. Not that it took much effort—the General’s war was spent preening in Whitehall, he was delighted to partake in another helping of battle even at a distance. Between school and holidays dawdled away at the houses of pals, I managed not to endure more than the occasional uneasy luncheon with him at the club.

From up here I can see the exposed timbers, looking like broken ribs, and the house appears unsteady and uneven, her former symmetry quite spoiled. An invalid with her shattered limb still attached. The lawns are sloshed into mud. Half the limes on the avenue are missing so that the driveway resembles a mouth with most of the teeth knocked out. The woodland under the ridge is balding in patches, where scores of the trees have been felled so that only the stumps remain, stubbling the hillside.

I sit down on an anthill and cry, relieved no one can see me. I wonder how the bloody hell we’re going to put the old girl back together. There are no paintings left to flog. No forgotten Turner lurking in the attic. Canning, the aged and recalcitrant estate manager, is muttering about wanting to retire. But then I swat away my doubts and revel in the pleasure of home. I take a breath of cold, larch-spiced air. Happiness rises up through me, fierce as brandy fumes.

***

In the dreary lull after Christmas, Jack informs us with great delight that he has persuaded the General to host a New Year’s Eve party. The General doesn’t like parties. They distract from the important things in life: namely shooting pheasant and fishing. Oddly, however, he enjoys a good war, even though it disrupts the same things. George is perfectly thrilled—he can’t quite believe Jack’s managed it. I’m not surprised. The General will agree to almost anything so long as it’s Jack who asks.

George and I set about readying the house. No mean feat as each day brings the discovery of yet more damage. The panel- ling in the great hall has been stripped away in places—whether for a lark or for kindling, we’ll never know. Not only is the mantelpiece missing on the grand inglenook, but part of the chimneystack has been knocked off so that when it rains, sleets or worse, water pours down the chimney and puddles on the hearth. Someone left the front door open a few nights ago, and when I stumbled up to bed I saw two blackbirds taking a bath. They looked quite self-possessed as they dabbled, eyeing me with great condescension as I swayed past with a glass of whisky. I thought I’d dreamed it, but when I came down in the morning, not a little hung-over, I found a spotted trail of white bird shit across the hall. The General appears to have neither the cash nor the inclination to make repairs. Planning for a party is a much pleasanter task than considering the larger future of the house.

On the morning of New Year’s Eve, George and I wander dismally from room to room, wondering how on God’s earth the place is going to be fit for a hundred of the county’s finest by the evening. At least we don’t have expectations to live up to. Even in the years before the war, Hartgrove wasn’t renowned for the calibre of its hospitality: there was always decent grog, but even then we couldn’t afford the staff or compete with the swagger of our neighbours. The family name is as old and threadbare as the sixteenth-century carpet that George and I hang on the wall in the drawing room in a futile attempt to keep the wind from sneaking in through the cracks in the plaster.

Jack, of course, isn’t with us. He imparted a variety of instructions over breakfast, informed us somewhat vaguely as to how many had accepted the invitation (‘Fifty or so, I should think – almost certainly not more than sixty, a hundred tops’) and then immediately left for the station—no doubt to collect his latest rosewater scented poppet. Clearly his role was simply to persuade the General to acquiesce to the party, not to bother with the actual organisation. I’m torn between irritation at Jack and pleasure—we’ve been apart for so long that there is still a novelty in his irksome habits. I’m oddly reassured to discover that the army has not reformed him.

One of the new dailies flicks a rag over the floor and the other pokes half-heartedly at the fire in the dining room that at half past nine is already threatening to give up with a whine of damp wood. There has been a parade of help through the hall in the last few weeks, each girl more belligerent than the last. None can stick it for more than a few days. It’s never quite clear whether they’ve walked out or whether Chivers has dismissed them or, as Jack suggested, buried them under the roses. We never do see the girls again. In the years before the war the house was mostly staffed with Chivers’ relatives. He always introduced them vaguely, saying, ‘Katy, Maud, Joan, the youngest daughter of my sister in Bournemouth,’ or ‘My Liverpool cousin’s girl’, but I suppose even Chivers had to run out of relatives at some point.

George and I survey the two surly maids, neither of them acknowledging our presence. Long gone are the days when our appearance would make them withdraw with a blush (not that I can remember, but so Jack tells me and perhaps it’s true).

‘I say, would you two lend us a hand getting the old place ready for a bash tonight?’ says George with false camaraderie and an awkward smile. George is never easy in company. I’m surprised that he’s so keen on the party—I suspect he’s pretending for Jack and my sakes. George is a thoroughly decent fellow, the best I know.

The girls look up. They do not smile back. They know instantly we’re amateurs. I fear it’s hopeless. We need Jack. Jack has all the charm; within two ticks he’d have the two girls eager to help, just to please him.

‘We got a lot to get through,’ says the larger of the girls.

‘We’re only paid through till twelve.’ She’s stout with deep-set brown eyes, like a pair of little wet stones.

‘Oh, gosh, bother,’ says George, deflating. I can hear him cursing Jack in his head for going off and leaving us like this.

I reach into my pocket, pulling out a portion of the General’s Christmas cash (‘Presents, unless they’re guns, are for girls’). I stuff it into the large maid’s stubby fingers. ‘When you’re finished for the morning, then.’

At twelve on the dot, they reappear in the drawing room, ready to help. They’re almost smiling. I wonder how much of my Christmas money I handed over, but I don’t care. I want this bash to be splendid. Jack and George have had parties in the mess, and they’ve travelled, seen things. Terrible things, perhaps, but at least they’ve been somewhere, done something. I spent the whole war at school. As we hunt out unbroken chairs from the four corners of the house, I try once again to ask George about it. I’ve attempted to persuade Jack and George to divulge details on various occasions with a notable lack of success.

‘What was it actually like? I think it’s rotten that you won’t tell me.’

He shrugs. ‘There’s not much to tell. In the most part it was frightfully dull.’

‘And in the other part?’

‘Unpleasant.’

‘Dull or unpleasant, that’s all?’ I ask, incredulous that this is all he’ll give me.

‘Mostly yes. Sometimes, when we were particularly unfortunate it was dull and unpleasant.’

I wonder if he’s teasing me, but that’s not like George. He doesn’t like to be ribbed himself, so rarely pokes fun at anyone else. We set down a small and only slightly stained sofa in the corner of the drawing room, pausing for a minute to catch our breath.

‘I can’t really picture you as a soldier, George.’

He smiles. ‘No, neither could I. I think that was part of the problem.’

‘What was the other part?’

He chuckles but doesn’t answer. ‘It’s jolly nice to be home. I missed the rain. Never thought that was possible but it is. Sunshine’s all very well but I’ve discovered that what I like best is the surprise of it after rain.’

I’m not sure what to say to this. Freezing rain is smashing against the windows, sneaking in through the ill-fitting panes and making small pools on the sills. We could do with a surprise of sunshine about now.

‘What were the other chaps like?’

‘Oh, all sorts. Every type. You know.’

I don’t know at all. I sigh and abandon my questioning.

Cambridge is pleasant enough—they’re decent fellows, precisely the sort I knew at school—but I hanker for some- thing different, less familiar. I can’t study music (chaps like us don’t study music. It simply isn’t done, according to Father) so the entire rigmarole feels utterly pointless, a dreary extension of school. If the war were still going on, I’d be in the thick of it instead of banished to endure cosy little tutorials in fireside snugs and listen to the assorted triumphs of Henries Tudor. And if I can’t have music, then I’d like a bit of war. I can’t say this to anyone. Even Jack’s wayward grin would falter and George, well, George would quietly walk away, head bowed. The General would approve the sentiment and that would be the worst condemnation of all.

***

The guests arrive meticulously late at a quarter to nine. In the dark the house doesn’t look quite so dilapidated. Candlelight, branches of holly and carefully placed globes of mistletoe conceal the worst of it. With the help of the two girls, George and I have made a pretty decent show. There’s a surprising amount of wine. When the house was requisitioned, the General didn’t fuss about packing away the carpets or the furniture (all strictly third rate anyhow—more decrepit than antique) but he and Chivers did hide away the good drink. They had the gardener build a false wall in the cellar, and while the soldiers graffitied obscenities in the downstairs loo they didn’t defile the pre-war burgundy, so in the General’s view the place has survived unscathed in essentials.

The night is cold, several degrees below freezing, and even before midnight the ground glints, thick with frost. The yew hedges are unkempt, overgrown from years of neglect and brushed with white like a drunk’s untrimmed beard. It’s too icy for cars—for those that still own them anyhow—and most people choose to walk. We’ve staked torches along the driveway and they flare out, banners of red flame in the darkness. The gloom provides a mask of perfect restoration and from outside the house looks splendid once again. You can’t see that the southern wing is burned out or that several windows along the front are boarded up or that the lawns are mown only by the sheep, at present snoozing in the shelter of the garden wall. All the party guests perceive is the yellow light spilling from the unbroken bay windows onto the terrace, ivy patterning the sandstone porch and the frost feathering the slate roof. I vow silently that if ever I’m rich, I’ll return the Hall to her former beauty so that she always looks like this, even in daylight. I drink a glass of sloe gin and watch the river, a black ribbon spooling noiselessly below.

‘Jack’s still not back, blast him.’

George is angry. Well, as angry as it’s possible for George to be. I really can’t picture him as a soldier, sallying forth full of rage and fury. He glances around the crowd of party-goers, tense, his forehead sweaty. We need Jack to play host. Neither of us is up to the task. George huffs and grumbles. ’Every time. Every bloody time. He swans in, gives his orders and swans off again. I’m tired of it, Fox. Next time, he can do the hard work. Where the devil’s he got to anyhow?’

I say nothing. Jack’s undoubtedly in a pub somewhere, nestled beside a toasty fire with his latest popsy, having lost track of time after his second or third pint. We move inside and we’re immediately engulfed in fur. The county girls have cracked them out again, now the war’s done and it’s no longer vulgar. I’m enveloped in the camphor whiff of mothballs and armpit.

‘Vivien. Caroline. How wonderful to see you.’ The girls incline their cheeks to be kissed.

‘Freezing, isn’t it? Where’s Jack?’

I deflate. No one even comments on the constellation of candles we’ve dug out or the huge log we’ve managed to drag inside that roars and crackles in the mantel-less hearth. A gramophone that wasn’t new before the war scratches out a tune, but it isn’t loud enough to be heard over the voices. No one dances. Half a pig with a tennis ball in its mouth lazes on the vast hall table. Chivers presides with a knife long enough to be a sword but I notice that only the men are eating. The women veer away from the spectacle, slightly revolted. We didn’t think of providing anything else. George and I assumed a pig would do it. Vegetables seemed superfluous.

One of the girls wafts over. Her dress is made of a fine, gauzy fabric and her skin is speckled with gooseflesh.

‘Hello, Fox. Splendid show. It’s all thoroughly charming.’

‘Is it, Vivien?’

She laughs. ‘No. Not really. But you’ve tried terribly hard and that’s charming enough. But in a house of men, what could anyone expect?’

‘Have some pig. If you eat, then the other girls might follow.’

She takes my arm. ‘All right but only if you tell me where your dastardly brother’s got to.’

At least there’s enough to drink. Everyone clusters near the fire, which is starting to smoke. I turn off the gramophone; the incessant scratching is making my ears itch. It’s only half past ten. God knows how we’re going to make it to midnight. Everyone appears to be waiting for something but we’ve planned nothing else.

The General moves through the crowd, a cigar in one hand (even during the war he never seemed to be short; I wonder what poor Chivers had to do to secure the things), and attempts small talk. If I wasn’t so anxious about the failure of the party, I’d be amused. The girls listen with toothy smiles that match their tiny strings of polished pearls—they’re all far too well bred to allow their boredom to show and everyone remains afraid of the General. He’s an old dog but one always senses the snarl and ill-humour under the curl of his moustache.

And then, all at once, the uneasy chatter blooms into laughter. Just as the applause of the audience signals the arrival of the conductor, I know without turning to look that Jack has arrived. I can’t quite make out the girl with him. She’s small and half concealed by the throng that instantly forms around Jack.

‘Right. Lead me to the drink,’ he cries.

The crowd part to let him pass and now I see a slight, dark-haired girl, her little gloved hand tucked into his arm. Jack signals to me. I cross the room. I stop, quite still. I recognise her.

‘Fox. This is Edie. Edie Rose.’

‘Of course. Yes. Edie. Miss Rose. A real delight. I’m a pleasure. To meet you. ‘

To my horror, I feel colour rising to my cheeks. Edie only smiles.

Inevitably the girls I like are already Jack’s girls. Each time he was on leave he’d show up to lunch with another wide-eyed, slim-legged thing who would flap a tear-soaked handkerchief as his train pulled out of the station and pen him letters that, knowing Jack, he never read. I’ve seen pictures of Edie of course. I even kept a postcard of her in my school trunk—she’s the nation’s sweetheart, as well, it seems, as being Jack’s—but seeing her standing in our mildew-ridden hall, amongst the press of girls in their well-worn frocks and the usual chaps with their ruddy cheer and their muddy shoes, I nearly forget to breathe. She’s smaller than I imagined from her photograph. Even in the midst of my awe, I notice how tired she looks.

Holding my elbow, Jack steers me through the crowd to a corner, with Edie still attached to his other arm.

‘There’s no music, Fox.’ He frowns, troubled.

‘No, the gramophone’s broken.’

‘Dammit, Fox. That thing’s quite useless anyhow. You should have hired a band.’

I sag, about to apologise and concede that that would have been a jolly good idea, when I remember Jack bloody well left us to it. I’m ready to snap back and ask him what I was supposed to hire a band with, since the General is hardly awash with cash, but Jack’s already turned away and is pleading quietly with Edie.

‘Go on, darling, be a doll. Just one.’

‘It’s never just one, Jack, you know that.’

‘All right, two then.’ He grins and strokes her cheek. ‘It would mean the world to young Fox here.’

Jack’s trying to persuade Edie to sing. I’m torn. I want to hear her sing, I really, really do, but she looks exhausted. She wrinkles her forehead and chews her fingernail in a sudden, childlike gesture, then gives a little sigh.

‘Yes, all right, I’ll do it. But one short set and that’s all. No requests. No encores.’

I’ve never heard a girl speak so firmly to Jack. He places a solemn kiss on her lips.

‘Agreed, madam.’

‘And now, you lured me here with promises of champagne. Are you all talk, Jack Fox-Talbot?’

With playful remonstration he leads her away and presents her with a glass of the General’s best pre-war Veuve Clicquot. I can’t help but stare after them. Edie might be the one who’s famous but the same aura of glamour shines on Jack. When we were children our grandmama played several games with us but her favourite was to pluck a buttercup and hold it under our chins. If it cast a yellow glow, she’d declare, ‘Yes, Little Fox likes butter very much indeed,’ and we’d squeal, perfectly delighted. My brother lives permanently in that buttery glow.

As I watch Edie and Jack colluding by the fire, they seem set apart from everyone else—like figures in an old master in a gallery full of amateur works—I feel a pulse of envy, hot and sharp. George perceives the direction of my gaze. George always does.

He chuckles. ‘Forget it, Fox. Not a chance.’ I look away, pretending not to understand.

I don’t pay attention for the rest of the party. The minutes drift by. Edie Rose will sing us into the New Year. This soggy failure of a party is transformed into a triumph. Everyone will talk about it for years to come. The church bells boom the half-hour and I look around for Edie but I can’t see her.

‘Hello. Harry, isn’t it?’ She’s beside me.

‘Yes. That’s right.’

I notice that she has a dot of a mole on her left cheek. I want to reach out and brush it with my fingers. I wonder whether Jack already has.

‘Jack tells me that you can sing and play the piano.’

‘Yes.’

Silently I curse myself. I want to appear dashing and sophisticated and yet in her company I’m apparently unable to stutter more than monosyllables.

‘Will you play for me, Harry? I’m frightfully tired. I don’t want to sing alone tonight.’

‘I would. But—the piano. She’s not in tip-top condition. She’s had rather a hard war, I’m afraid.’

Edie laughs. ‘She?’

‘I’m sorry. I always think of her, it . . .’

Edie reaches out and touches my arm. ‘It’s terribly sweet of you.’

I’m nettled. I don’t want her to think I’m sweet. I’m not a child.

‘The army moved the piano into the mess bar. Goodness knows what’s been poured over the keys. Not to mention the general damp. When I tried to tune her—it—one of the strings just snapped.’

‘Please play for me, Harry.’

‘Fine. But—’ I remember she said no requests.

‘What is it?’

‘Will you sing one of your early pieces? “The Seeds of Love” or “The Apple Tree”? Not that I don’t like the wartime songs, of course.’

This isn’t true. I dislike Edie Rose’s wartime hits intensely. They’re patriotic guff. Tunes in one shade of pillar-box red. I’d walked out of a café once when ‘Shropshire Thrush’ came on the wireless, even though I’d already paid.

Edie gives me an odd look. ‘They won’t like it.’

She glances at the assembled crowd and I’m pleased that she’s no longer counting me amongst them. Jack bounds over and kisses her on the cheek, tucking a curl behind her ear with easy familiarity.

‘It’s time, old thing. Or do you want this first?’

With a flourish he produces from his pocket a disintegrat- ing fish-paste sandwich. Edie shakes her head and I point mournfully at the hog squatting on the table. ‘What’s wrong with my pig? No one seems to want it.’

‘It’s splendid, Fox. Just not really Edie’s thing.’ She turns to me. ‘Well, Harry? Shall we?’

Edie doesn’t sing my song. I sit at the rickety piano and cajole the keys into some sort of accompaniment, feeling as if I’m riding shotgun on an unsteady, half-dead nag that might either bolt or flop into the hedgerow at any moment. Edie’s a true professional and doesn’t let the screwball sideshow rattle her. She lulls the county set with that honeysuckle voice as she floats through the wartime hits that made her famous but which I cannot abide. I’m sweating from the effort of forcing the piano to obey and I have a headache. It’s past midnight and we’ve slid into 1947 and I haven’t even noticed. I need a drink and a clean shirt. The guests cheer and toast Edie and then me as she hauls me to my feet. They holler and even the General raises a glass.

‘Shall we get out of here?’ she whispers through her teeth, giving them a playful curtsey.

‘Dear God, yes.’

We race outside before the crowd can smother her with well-lubricated enthusiasm. She lights me a cigarette and I take it, somehow too embarrassed to confess I don’t smoke. I can’t stop staring at her. She smiles at me, and it’s slightly lopsided as though she’s thinking of a mischievous and inappropriate joke. It’s horribly attractive.

‘So how come when all three of you boys are Foxes, you are the only one called “Fox”?’

I swallow smoke, trying not to cough, grateful that in the dark she can’t see my eyes water.

‘I was always “Little Fox” but somehow now that I’m eighteen and nearly six foot, it seems, well, silly. So now I’m just Fox.’

‘I see. Fox suits you. Although I’ve always liked the name Harry.’

I wonder whether she’s flirting with me, but I’m so unpractised that I can’t tell.

‘You need a new piano,’ she says.

‘And a new roof and a hundred other things. But I thought I played her valiantly.’

‘With absolute chivalry. A lesser man would have chopped it, sorry, her, up mid-performance for kindling.’

‘Are you trying to charm young Fox here?’ asks Jack, appearing at my side clearly unperturbed by the prospect that I’m thoroughly put out.

A trio of girls and their beaus step out onto the terrace in Jack’s wake. Oblivious, he pulls people along as if they were the trail behind a shooting star. They say he was one of the best officers in his battalion, that his men would follow him anywhere, do anything for him. I believe it.

The low balustrades of the terrace are smashed, but spread with frost they catch in the light and glisten.

‘I didn’t get my song,’ I complain. Drink has made me bold.

‘You first,’ says Edie. ‘It’s only fair and Jack says you can sing.’

‘He can, he can. He’s splendid,’ says Jack. My brother has the kindness and generosity of the utterly self-assured.

‘Fine. What shall I sing?’

‘That one you do for me and George. I like that one. He’s terribly clever, he wrote it himself.’

I wince at his enthusiasm. Jack’s referring to a bawdy and frankly filthy ditty I made up to amuse him and George, but it’s too late and Edie’s turning to me expectantly.

‘In that case I demand a Harry Fox-Talbot original. I won’t accept anything less.’

I rack my brains for something neither too simple nor too rude. Others have gathered on the terrace, but I don’t mind. I never mind an audience for music. According to my brothers, before Mother died I used to come downstairs and sing for dinner guests in my nightshirt. I hope Jack hasn’t told Edie this. I can’t ask him not to because then he certainly will. I clear my throat.

‘All right. Here you go. This isn’t strictly written by me, but I heard it once upon a time and this is a tidy variation on a theme.’

I’m not a distinguished singer, but my voice is pleasant enough and, I suppose, expressive. I can make a few instruments say what I’m thinking—pianos, church organs and my own voice. I’m not quite six foot and not quite handsome. My eyes aren’t as blue as my brothers’ but I’ve observed that when I sing girls forget I’m not as tall as they’d thought and not as handsome as they’d hoped.

I sing without accompaniment. I don’t look at Edie or the other girls. The frost is thick as snow and I watch the song rise from my lips as steam. I’ve never seen a song fly before. The words drift over the lawn. It’s one of Edie’s old songs from before the war. I sing the names of the flowers and they float out into the darkness—yellow primroses and violets bright against the wintry ground. I sing a verse or two and then I stop. I can fool them for a short while, but I know if I go on too long my voice can’t hold them. That takes real skill, and a real voice. A voice like Edie Rose’s.

‘Jolly good. Bloody marvellous,’ shouts Jack and claps me on the back.

The others applaud and the girls smile and, for first time that evening, try to catch my eye. I should make the most of this—it’s a temporary reprieve from invisibility. The effect of a song is much like a glass of champagne and lasts only as long. I glance at Edie. She doesn’t look at me and she doesn’t clap with the others.

Excerpted from THE SONG OF HARTGROVE HALL by Natasha Solomons

Copyright © 2015 by Natasha Solomons. Excerpted by permission of Plume. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Song of Hartgrove Hall

- Genres: Fiction

- paperback: 400 pages

- Publisher: Plume

- ISBN-10: 0147517591

- ISBN-13: 9780147517593