Excerpt

Excerpt

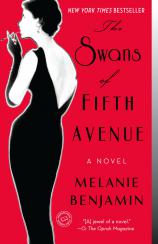

The Swans of Fifth Avenue

Once upon a time—

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times—

There once was a man from Nantucket—

Truman giggled. He covered his mouth like a little boy, and tittered until his slender shoulders shook, his blue eyes so gleefully mischievous that he looked like a statue of Pan come to life.

“Oh, Big Mama! I am such a naughty imp!”

“True Heart, you are priceless!” Slim had laughed, too, she remembered, laughed until her ribs ached. Truman did that to her in those glorious early days; he made her laugh. That was it, really. The simple truth of the matter.

When he was young, back in 1955, when they were all young—or, at least, younger—when fame was new and friendships fledgling, fueled by champagne and caviar and gifts from Tiffany’s, Truman Capote was a hell of a lot of fun to be around.

“Once upon a time,” Slim had finally pronounced.

“Yes. Well . . . ,” and Truman drawled it out in his theatrical way, adding several syllables. “Once upon a time, there was New York.”

New York.

Stuyvesants and Vanderbilts and Roosevelts and staid, respectable Washington Square. Trinity Church. Mrs. Astor’s famous ballroom, the Four Hundred, snobby Ward McAllister, that traitor Edith Wharton, Delmonico’s. Zany Zelda and Scott in the Plaza fountain, the Algonquin Round Table, Dottie Parker and her razor tongue and pen, the Follies. Cholly Knickerbocker, 21, Lucky Strike dances at the Stork, El Morocco. The incomparable Hildegarde playing the Persian Room at the Plaza, Cary Grant kneeling at her feet in awe. Fifth Avenue: Henri Bendel, Bergdorf’s, Tiffany’s.

There was a subterranean New York, as well; “lower” in every meaning of the word. Ellis Island and the Bowery and the Lower East Side. The subway. Automats and Schrafft’s, hot dogs from a cart, pizza by the slice. Chickens hanging from windows in Chinatown, pickles from a barrel on Delancey. Beatniks in the Village with their torn stockings and dirty turtlenecks and disdain for everything.

But that wasn’t the New York that drew the climbers, the dreamers, the hungry. No, it was lofty New York, the city of penthouses and apartments in the St. Regis or the Plaza or the Waldorf, the New York for whom “Take the ‘A’ Train” was a song, not an option. The New York of big yellow taxis in a pinch, if the limousine was otherwise occupied. The New York of glittering opening nights at the Met; endless charity balls and banquets; wide, clean sidewalks uncluttered by pushcarts and clothing racks and children playing. Views of the park, the river, the bridge, not sooty brick walls or narrow, dank alleys.

The New York of the plays, the movies, the books; the New York of The New Yorker and Vanity Fair and Vogue.

It was a beacon, a spire, a beacon on top of a spire. A light, always glowing from afar, visible even from the cornfields of Iowa, the foothills of the Dakotas, the deserts of California. The swamps of Louisiana. Beckoning, always beckoning. Summoning the discontented, seducing the dreamers. Those whose blood ran too hot, and too quickly, causing them to look about at their placid families, their staid neighbors, the graves of their slumbering ancestors and say—

I’m different. I’m special. I’m more.

They all came to New York. Nancy Gross—nicknamed “Slim” by her friend the actor William Powell—from California. Gloria Guinness—“La Guinness”—born a peasant in a rural village in Mexico. Barbara Cushing—known as “Babe” from the day she was born, the youngest of three fabulous sisters from Boston.

And Truman. Truman Streckfus Persons Capote, who showed up one day on William S. and Babe Paley’s private plane, a tagalong guest of their good friends Jennifer Jones and David O. Selznick. Bill Paley, the chairman and founder of CBS, had gaped at the slender young fawn with the big blue eyes and funny voice; “I thought you meant President Truman,” he’d hissed to David. “I’ve never heard of this little—fellow. We have to spend the whole weekend with him?” Babe Paley, his wife, murmured softly, “Oh, Bill, of course you’ve heard of him,” as she went to greet their unexpected guest with her legendary warmth and graciousness.

Of course, Bill Paley had heard of Truman Capote. Who hadn’t, in Manhattan in 1955?

Truman, Truman, Truman—voices whispered, hissed, envied, disdained. Barely thirty, the Boy Wonder, the Wunderkind, the Tiny Terror (this last, however, mainly uttered by other writers, it must be admitted). Truman Capote, slender, wistful bangs and soulful eyes and unsettling, pouty lips, reclining lazily, staring sultrily from the jacket of his first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms. A novel that neither Babe nor any of her friends such as Slim or Gloria had bothered to read, it must be admitted. But still, they whispered his name at cocktail parties, benefits, and luncheons.

“You must meet—”

“I’m simply mad about—”

“Of course you know—”

Truman.

“I introduced you to him first,” Slim reminded Babe after that fateful weekend jaunt to the Paleys’ home in Jamaica; that startling, stunning weekend when Babe and Truman had found themselves blinking at the first dazzling sunrise of friendship, still so new that they didn’t quite understand that it was friendship, this thing that had cast a spell over the two of them to the exclusion of mere mortals. “You just don’t remember. But he was mine, my True Heart. It’s not fair that you’ve stolen him from me.” And Slim pouted and shook her blond hair, always hanging over one eye, looking more like Lauren Bacall than did Lauren Bacall, which was only appropriate, since Lauren Bacall had modeled herself after Slim. “Around the time he was working on the screenplay of Beat the Devil, Leland brought him home for dinner one night. Don’t you remember?”

“No, it was I who first discovered him,” Gloria insisted with a flash of her exotic dark eyes; that flash that always threatened to expose her real origin, concealed so nearly completely beneath the Balenciaga dresses and Kenneth hairstyles—and studied British accent. “I’m surprised, Slim, that you don’t recall. It was soon after he adapted The Grass Harp for Broadway. I don’t generally go in for Broadway, naturally,” she said with an arch look at Slim, who bristled. “But I’m very glad I went to that opening night. I told you all about him then, Babe.”

“My dear, no. I invited him for the weekend, in Paris, don’t you recall?” Pamela broke in, her voice so veddy, veddy British that they all, instinctively, leaned in to hear her (and they all, instinctively, recognized the ploy for what it was, and the many times their husbands had done the same thing, only to encounter Pamela’s magnificent cleavage displayed in a low-cut Dior). “Long before any of you—back when he had just published Other Voices, Other Rooms. Bennett Cerf, you know, the publisher”—and she could barely suppress a shudder; one simply did not like to admit one knew those types—“asked me if I could entertain this young novelist of his, as he was rather nervous about reviews. You were there, Babe. I’m certain of it.”

“Ladies, ladies,” admonished C.Z., unflappable and untouchable as ever, never quite “in” but never quite “out” of their world—simple and uncomplicated, a Hitchcock blonde with a sunny smile (and a clenched, exceedingly proper Boston drawl). But C.Z., they all knew, was happier puttering around in her garden, spade in hand, or tending to her horses than she was lunching at Le Pavillon. “I don’t usually care about this sort of thing, but I do believe I was the one who introduced Truman to Babe. We were shopping at Bergdorf’s. Truman is marvelous at picking out just the right handbag. You were there that afternoon, Babe.”

“No, I propose it was on our yacht,” Marella said in her uncertain English; her entire manner was shy and tentative around her friends, since she was much younger than they were, never entirely sure of her place, despite her fabulous wealth and exquisite beauty—and a face that Truman had pronounced “what Botticelli would have created, had Botticelli had more talent!” “Alec Korda brought him along, one summer. I believe you and Bill were there, Babe, were you not?”

Babe Paley, cool in a blue linen Chanel suit that did not crease, no matter the radiator heat of a New York summer, didn’t reply; she merely looked on, amused, as she removed her gloves, folded them carefully, and slipped them inside her Hermès alligator bag. Seated in the middle of the best table at Le Pavillon, she surveyed her surroundings.

This was her world, a world of quiet elegance, artifice, presentation. And luncheon was the highlight of the day, the reason for getting up in the morning and going to the hairdresser, buying the latest Givenchy or Balenciaga; the reward for managing the perfect house, the perfect children, the perfect husband. And for maintaining the perfect body. After all, one generally dined at home, or at a dinner party; why else employ a personal chef or two? But one went out for luncheon, at The Colony or Quo Vadis. But especially Le Pavillon, where the owner, Henri Soulé, displayed his society ladies like the objets of fine art that they were, seating them proudly in the front room, spreading them out in plush red-velvet banquettes, setting the table with the finest linen, Baccarat glasses, exquisite china and silver, and cut crystal bowls of fresh flowers. They drank their favorite wine, pushed the finest French cuisine around their plates (for in order to wear the kind of clothes and possess the kind of cachet to be welcome at Le Pavillon, naturally one could not actually eat), gossiped, and were seen.

Photographers were always gathered on the sidewalk outside, waiting to snap the beautiful people inside, and Babe, tall, regal, a gracious smile on her face, was the most sought-after of all, to her friends’ eternal dismay and her own weary disdain—although the most observant, like Slim, might notice that Babe would pause, imperceptibly, if no photographer happened to be around, as if looking, or wishing, for one magically to appear.

Why was Babe Paley such a favorite? Why was she the most fussed over, the most sought out for a quick, reverent hello by those not privileged to be seated with her? She was not the most beautiful; that honor must go to Gloria Guinness, with her exquisite neck, lustrous black hair, and flashing eyes. She was not the most amusing; that was Slim Hayward, with her quips and her quick wit, honed at the feet of men like Ernest Hemingway and Howard Hawks and Gary Cooper. She was not the most noble; no, that would be a tie between the Honorable Pamela Digby Churchill, daughter of a baron, ex-daughter-in-law of a prime minister, and Marella Agnelli, a bona fide Italian princess, married to Gianni Agnelli, the heir to the Fiat kingdom.

It was her style, that indefinable asset. It was said that the others had style but Babe was style. No one noticed Babe’s clothes, for instance; not at first, even though she was always clad in the chicest, most exquisite designs. They noticed her, her tall, slender frame, her grave dark eyes, the way she had of holding her handbag in the crook of her arm, the simple grace with which she pushed her sunglasses on top of her hair or unbuttoned a coat with just one hand, allowing it to fall elegantly from her shoulders into the always-waiting arms of a maître d’.

What they did not notice was the loneliness that trailed after her, along with the faint, grassy scent of her favorite fragrance, Balmain’s Vent Vert. The loneliness that, despite fabulous wealth, numerous houses, children, the most vibrant and powerful husband of all her friends, was her constant companion—or, at least, had been. Until now.

“It doesn’t really matter,” Babe finally pronounced, settling it once and for all. “I’m simply so very glad to know him. To Truman!” And she raised a flute of Cristal.

“To Truman!” her five friends all echoed, and they toasted to their latest find, excited and hungrily anticipating fresh amusements galore, nothing more.

“To Truman,” Babe whispered to herself, and smiled a private little smile that none of her friends had ever seen before. But the Duchess of Windsor had just entered the restaurant, her harsh little face turned first to the left, then to the right, as if she really were royalty, igniting a small wildfire of catty conversation—“Isn’t the duke the most boring man you’ve ever met? But those jewels! The one thing he’s ever done right!”—and none of Babe’s friends was even looking at her.

Except for Slim, who narrowed her eyes and bit her lip. And wondered.

Excerpted from THE SWANS OF FIFTH AVENUE by Melanie Benjamin. Copyright © 2016 by Melanie Benjamin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Swans of Fifth Avenue

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 400 pages

- Publisher: Bantam

- ISBN-10: 0345528700

- ISBN-13: 9780345528704