Excerpt

Excerpt

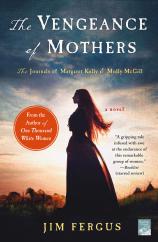

The Vengeance of Mothers: The Journals of Margaret Kelly & Molly McGill

LEDGER BOOK I

In the Camp of Crazy Horse

We curse the U.S. government, we curse the Army, we curse the savagery of mankind, white and Indian alike. We curse God in his heaven. Do not underestimate the power of a mother’s vengeance.

(from the journals of Margaret Kelly)

9 March 1876

Me name is Meggie Kelly and I take up this pencil with my twin sister, Susie. We got nothing left, less than nothing. The village of our People has been destroyed, all our possessions burned, our friends butchered by the soldiers, our baby daughters gone, frozen to death on a godforsaken march across these rocky mountains. Empty of feeling, half-dead ourselves, all that remains of us intact are hearts turned to stone. We curse the U.S. government, we curse the Army, we curse the savagery of mankind, white and Indian alike. We curse God in his heaven. Do not underestimate the power of a mother’s vengeance.

We have reached the winter camp of Crazy Horse on the Powder River. We been here six days now. The Lakota family who took us in has given us a stack of ledger books and a rawhide pouch full of colored drawing pencils. These belonged to one of their tribal artists who was killed in battle. Because me and Susie don’t speak Lakota, only Cheyenne and sign talk, they wished us to make drawings of the attack on our village so they could see for themselves how it went. These are a real visual people, and we got no other way to communicate with them. We did the best we could, but me and Susie are not real good drawers.

The thing is we can write a little better, at least, I can, though we ain’t fancy educated girls, like our old friend May Dodd. Aye, we may have all been from Chicago, but me and Susie grew up on the streets, orphans who lived by our wits … and our bodies in times of need … because we was a handsome pair of lassies back then and the fellas was always sniffin’ around after us. When we was split up and sent to different foster homes, one of my families gave me a little more teaching than did Susie’s, who just made her a servant like in many foster homes, didn’t care if she knew how to read or write, long as she could do their housework and laundry. So when she has somethin’ to say here, she is just going to tell me and I will write it down best I can, and together we are going to keep up this journal in honor of our friend May. For Brother Anthony tells us that she, too, is dead, along with all the others, except Martha. But just now we have no tears left to shed … we expect that will come later.

The night before the Army attack, a number of us white women slept in Brother Anthony’s tipi. Earlier that evening we had watched our Cheyenne husbands dancing proudly over their trophies of war—a bag of twelve severed baby hands taken in a raid that day against their enemy, the Shoshone. They had ridden with a band of other rash young men out to prove themselves for the first time in battle. None of the experienced warriors such as Little Wolf, Hawk, or Tangle Hair had participated, but it is the tradition of the tribe that all must attend the victory dance. As they pranced, these boys chanted the tale of their triumph, they sang that in taking these babies’ hands they had captured the power of the Shoshone nation … aye, the grand power of a baby’s hand …

After the horror of what we saw the lads had done, we white women fled from the celebration, and we could not bear to go back to our own lodges, could not bear to look upon our husbands ever again. We slept that night in Brother Anthony’s lodge, and we tried to make sense of something that made no sense at all. What were those boys thinking? How could they have done such a thing? And maybe, after all, what happened in the morning was God’s just punishment … though still we curse him for putting us and our children on earth and then abandoning us.

Even though we were flyin’ white flags of surrender, the soldiers attacked the village at dawn. We woke to bugles blowing, galloping horse hooves pounding frozen earth, the sharp metal-on-metal sound of swords unsheathed, gunfire, and the battle whoops of the invaders. Course, those of us with babies had but one thought—to run, to save our children. Me and Susie gathered our twin girls in their baby boards and strapped them to our breasts. Brother Anthony went immediately through the tent flap and with no fear for his own safety raised his arms to the heavens and begged the soldiers to stop this madness. But the killing had already begun, and the soldiers did not heed Anthony’s pleas.

As our own men took up their arms, the women, children, and elders ran from the tipis, confused and terrified … they were knocked down and trampled by the soldiers’ horses, shot by rifle and pistol, slashed by swords, there were screams and cries everywhere, chaos and death … everywhere chaos and death.

We ran for our lives with the others. We saw some of our own fall to the soldiers and we tried to help ’em best we could. But finally we had to make the terrible choice to leave them where they fell, so we might save our own babies. The attack went on for several hours, as the men of the village fought bravely to defend us. But they were no match for the Army. We who managed to reach the hills sought any shelter we could. It was so cold … so bloody cold …

After the cavalry secured the village, they went about their business of destroying it and finishing off the wounded. Crouched shivering in the rocks, trying to keep our babies warm, we heard the terrible sounds of the killing. Some bravely sang their death songs until they were silenced. We heard the keening of mothers mourning their dead children, before they, too, were slaughtered. We heard screams from some of our women, and we knew what was happening to them … before they, too, fell quiet.

With the wounded finally dispatched, the soldiers began to stack all our goods in huge piles and light them afire, lighting, as well, the tipis, leaving nothing for us to salvage, nothing for us to return to. The cold flames rose, offering us no warmth, the smoke bearing its sickening odor of burning human flesh …

It was dusk by the time the cavalrymen remounted and rode off. Brother Anthony joined us in the hills, came to us weeping … “the horror, the horror,” he cried. “I tried to protect God’s children, I tried to save them from the soldiers’ madness. But there were too many, too many…”

“Where is May?” I asked. “Is May alive?”

Anthony could only shake his head, so broken up was he by grief.

“Is anyone alive?”

Again he shook his head. “All dead,” he managed to say, “all dead except for Martha and her baby. Captain Bourke has taken charge of them … he was riding with the soldiers, but not as their commander … he, too, tried to stop the carnage, but their bloodlust was not to be denied … The captain swore to me … he swore to me on his life and in the name of God that he would see that Martha and the child were returned safely to Chicago.”

Aye, Martha was May’s best friend, and besides me and Meggie, she and her baby were the only other survivors of our entire group. It offers us great solace to imagine them back safe in their home … a place that seems to us so far away.

That night under the cold full moon, Little Wolf led us across the mountains toward the village of Crazy Horse. We ain’t got words to tell of the suffering we endured on that journey, the children and the wounded who died, including our own Daisy Lovelace and her baby that first night, and on the second night me and Susie’s twin girls. We were told to leave their bodies in a tree, for there was no timber available to build a burial scaffold in the manner of the Cheyenne, and the ground was frozen so they could not be interred as was our own custom. But we could not bear the thought of the carrion pecking at their wee bodies, and so we carried them in their baby boards the rest of the way to Crazy Horse’s camp … we feel still, and will forever, the weight of the tiny frozen corpses heavy on our breasts.

And so you see we got nothing left but our hearts of stone.

The Lakota, too, are being pursued by the Army, and they have little to share with us. Captain Bourke told Brother Anthony that when the Army attacked our village, they thought it was the village of Crazy Horse, he was the one they were really after. All that death, all that pain and destruction and heartbreak … because the Indian scouts who were guiding the troops made a mistake. But you know what the soldiers say around the fort? We heard it ourselves when we were trading at Fort Laramie before winter came on. They say the only good Injun is a dead Injun. Who cares whether they be Cheyenne or Lakota? I guess the Army decided that white women who consort with savages also deserve to die … and their half-breed babies as well, even though our government sent us here in the first place.

Crazy Horse himself is a strange man. He hardly speaks, stays to himself, and does not socialize with the rest of the tribe. Even his own people think he’s a peculiar fella. Although the Lakota are allies of the Cheyenne, our chief Little Wolf has never cared for their people, has never learned their language, and has avoided contact with them as much as possible. Among other things, he thinks their women are loose. He and Crazy Horse do not get on together, and keep out of each other’s way. Maybe this is simply a matter of two great warriors from different tribes in a pissing contest in the manner of boys. Men are hopeless creatures, me an’ Susie lay all the violence and troubles of the world at their feet.

Little Wolf is angry for he feels that Crazy Horse has been stingy with us since we came here. It is true that the Lakota do not have much to give, but to the Cheyenne a lack of generosity toward those in need is the greatest of insults. Then again, though our arrival was not welcomed by the Lakota chief, it is true he has his own people to provide for. Game is scarce, the buffalo herds greatly reduced and scattered by the white settlers who wish to raise cattle on this land, and so they slaughter the wild native bovine to make room for their domesticated cows … in the same way that they slaughter the wild native Indians to make room for themselves.

Many of the people talk now of surrender. We got nothing. We kill and butcher our horses to eat. Others wish to fight on. Me an’ Susie will never surrender to those who murdered our babies. Never. We have taken a holy vow to fight the whites to the end, to kill and scalp as many bluecoats as we can. Brother Anthony came to our tipi today and has tried to talk to us, has tried to bring us back into “the arms of God who loves and keeps us,” says he.

“Is that so, Brother?” asks Susie. “An’ if he loves and keeps us so well, then why did he kill our wee infants? What did they ever do to deserve that? We curse God for his cruelty, his savagery … the fooking hypocrite who blames the very people for our behavior he himself created in his own image. What kind of arsehole is he anyway, Brother? Aye, we curse him and we damn him in the name of all mothers.” It is true that though we be identical twins, me and Susie still each got our own ways, and if anything she may the harder girl between us.

“It is not God who is cruel and savage,” the monk answers. “Those are the actions of men who have fallen from the path of our Lord, or who, perhaps, have never known it.”

“So what good is he then, Brother, if he hasn’t even the power to protect babies?”

“It is your grief that steals your faith, my children, your grief that speaks for you now. Not your hearts.”

“Our hearts are stone, Anthony,” says I, “and as stone they speak.”

“And with those hearts of stone,” says Susie, “we will bash in the soldiers’ brains, and with our knives, sharpened on those same stones, not only will we take their scalps, but also cut off their bollocks.”

“Right ya are, sister,” says I, “and those bollocks we will string together with rawhide and wear proudly around our necks as trophies of war.”

“Aye, Brother Anthony,” says Susie, “our husbands cut off the hands of Shoshone babies. The fools believed that in so doing they were capturing the power of the tribe … imagine that … But it is men’s bollocks that cause all the war, all the death and destruction in the world. That is where we will take our revenge.”

“Aye, Brother,” says I, “and as the legend of the mad Kelly twins grows across the plains, the soldiers will so fear encountering us that they will refuse the orders of their officers, they will mutiny and begin to desert, they will leave this country once and for all until all have fled.”

“The traders and the sodbusters and the cattlemen and the gold diggers, too,” Susie continues, “as they learn of our savage exploits, will be driven from the plains by sheer terror at the sound of our names. And then the People will live in peace and the buffalo and the game will return, and all will be as before.”

Anthony can only shake his head sadly. “Yes, my children, all will be as before,” says he. “Except that your infants will still be gone, and all your anger, all your hatred, all your schemes of bloody revenge will not bring them back.”

“Maybe not, Brother,” says I. “Maybe not … but do not underestimate the wrath of a mother’s vengeance. It is only that which keeps us alive, don’t ya see? We will stay here and fight to the end, because what else is there to do, where else do we have to go? And if we survive we will bear more babies for the savages, and we will make for them a better world ruled by mothers, not by the bollocks of men.”

15 March 1876

These past few days bring a false spring thaw, the snow melting on the surrounding hillsides. The wet rocks glisten and steam in the morning sun, the plains that stretch beyond the river bottom even showing a few patches of pale green grass. Brother Anthony has come again to our tipi to tell us that it is fixed now—Little Wolf is fed up with what he considers to be the stinginess of the Lakota, and he is leaving with most of the rest of our band to turn themselves in to the Red Cloud Agency at the Army’s Camp Robinson in Nebraska Territory. Aye, that is where the already surrendered Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho are now living, and where all those hostiles who have not yet turned themselves in have been ordered by General Crook to report … once they do, forbidden to leave again.

Only a handful of the other Cheyenne who have family here among the Lakota will stay, and those like me and Susie who would rather die than give up. We don’t blame Little Wolf, he’s the bravest man we’ve ever known, the finest leader and the toughest warrior, but his first responsibility as the Sweet Medicine Chief is to protect the people from harm, to feed and clothe them as best he can and it is for this reason that he has decided to surrender.

“You girls must go in with Little Wolf,” Anthony says to us again.

“Have we not made it clear to you, Brother,” says Susie, “that the Kelly sisters will never surrender?”

“Please, listen to me, my children,” says he. “You are white women. It is not a matter of surrender, for you are not at war with the Army or the United States government.”

“Aye, not at war with the Army or government, you say, Brother?” says I. “That would be grand news to us, wouldn’t it now, sister? But were it true, then who was it attacked us, who was it responsible for the death of our babies and all our friends?”

“This is now simply a matter of your own survival,” says the Brother, “of seeking food, shelter, and safe passage back to your homes.”

“But we have no homes to return to,” says Susie. “Have you forgotten, Brother, that we are felons? We will be returned to prison if we go back to Chicago.”

“No, Captain Bourke will see to it that this does not happen. As he has promised to do for Martha, he will see that you are cared for.”

“Aye, just as he saw to it that our peaceful winter village flying white flags of surrender was not attacked by the cavalry with which he himself was riding, ain’t that so, Brother Anthony?”

“The captain did not know it was Little Wolf’s village. They were misinformed by the scouts. He is filled with remorse and guilt over what happened, and will be for the rest of his life.”

“As well he should be,” says Susie.

“You girls are incorrigible,” Anthony says sadly. “Although I rather expected this answer from you. If you insist on staying, then please at least grant me one request.”

“And what would that be, Brother?” says I.

“There is a group of white women here.”

“White women?” Susie and me answer together as so often happens among twins. “And where in bejaysus did they come from? What are they doin’ here?”

“It appears that they were intended to be another installment of the Brides for Indians program,” says Anthony. “The wheels of government bureaucracy turn slowly, and as you well know communications out here are difficult. Evidently these women had already been sent to join the Cheyenne before word that the program was terminated had reached the proper authorities.”

“But how did they end up with the Lakota?”

“As I understand it, their warriors built a fire on the tracks to stop the train, and when it came to a halt, they attacked—overpowering the escort of soldiers, stealing the Army horses, guns, ammunition, and other kit meant to resupply the troops at Fort Laramie … and abducting the women. They are now being kept isolated in a guarded tipi on the edge of the village. I was allowed to meet with them, and, understandably, they are deeply distraught. I powwowed with Crazy Horse and the other Lakota leaders and did my best to convince them to let the women come with us to the agency. I explained that releasing them into my custody would be considered by the Army as an act of good faith on their part. But the chiefs flatly refused my request.”

“What do you want from us then, Brother?” asks Susie.

“I want you to help them, to look after them,” says he. “Anticipating that you would refuse to come in with us to the agency, I did at least manage to convince the chiefs to let you see the white women. My hope is that with your own experience among the Indians, you will be able to counsel these girls and see them through this ordeal.”

“Aw, holy Jaysus, Brother,” says I, “me and Susie ain’t no damn babysitters. We got more important business to attend to than looking after a bunch of crybaby white girls.”

“And what important business would that be, ladies?” Anthony asks. “I am simply asking you in the name of the Lord, in the name of Christian charity, to help a group of deeply distressed, captive women of your own race. You remember what it was like when you first came out here a year ago. You must yourselves have been terrified, although knowing you two as I do, I suspect you hid that fear behind your Irish bravado. At the same time, you had the support of each other and of your friends. You had a peaceful transfer into the hands of the Cheyenne, you were not violently abducted from a train and held hostage. A number of their party were also killed in the attack, which has further traumatized them. I beg you, do what you can to help these girls, counsel them, offer them succor and support, try to transfer to them some of your own fortitude. For all you have both suffered, for all you have endured, you are strong women, you are survivors. Give them some hope that they, too, can find a way through this predicament.”

“We don’t know much about hope, Brother,” says Susie.

“But I believe you do. And so does almighty God in his heaven.”

16 March 1876

And so me and Susie go to see these white women. The Lakota are keeping ’em in a communal tipi used by the Indians for official functions like war councils and powwows, a tipi so grand you can stand up inside it. It seems that the women of the tribe are a wee bit unhappy about the arrival of the white lassies and wish to have them isolated from the general population, particularly from their men. As all the tribes do with female captives, the Lakota squaws probably plan to make slaves of ’em. But you can be sure we’re not going to tell the lassies that part just yet. Nor do we intend to tell ’em straight out what happened to our group. We figure they must be scared enough as it is with what they already been through, and that’ll only scare ’em more.

As the Cheyenne do themselves when they go visiting, we thought we should bring some kind of gift for the white girls. Cheer ’em up a wee bit. But we got nothing ourselves besides the clothes on our back, so all we could think to give ’em was some of our stock of ledger books and colored pencils. We figured maybe that would at least give ’em something to do, other than to sit around all day long worrying about what was going to happen to ’em.

The young Lakota boy guarding the entrance opens the tipi flap for us and we duck inside. A fire burns in the center and the women are seated in a circle around it, wrapped in trade blankets or buffalo capes worn over their dresses. At first they seem a little confused to see us, frightened even. It is true that maybe me and Susie have a scary look about us after these last hard days of want and suffering and grief—identical twins with our red hair wild and tangled around our faces, bright green eyes and deathly pale complexions, bone skinny from hunger, dressed in ragged animal hides and ratty trade blankets given us by our Lakota family. Sometimes we catch sight of each other, and we share one of those twin mirror moments, realizing how much we have changed, how far we have come in this past year, so far that there is no turning back to the world we once knew.

A quick head count tells us that they are but seven in number. Although most of ’em look to be about our own age, they seem like mere girls to us, as if we ourselves have aged a full decade in our one year on the plains. They, too, are a wee worse for the wear, what we can see of their white-women clothes stained, frayed, and torn here and there. Still we can tell they’re makin’ an effort to keep themselves as tidy as possible in captivity, which is an important sign that they haven’t given up hope—their faces are clean, their hair in place. Though thin, they clearly ain’t starving, and it appears to us that the Lakota are treating them kindly and with respect, which is the way of these people.

“Alright, lassies,” says I straightaway to calm ’em, “you’ve nothing to fear from us. I be Meggie Kelly, and this be me sister, Susie. We might not be lookin’ our best, that’s the God’s truth, but we are white women ourselves as you can plainly see. Make a wee bit of room for us so we can sit down with you by the fire.”

Several of ’em scoot over to make space, and Susie and me get settled cross-legged. Pale late-afternoon light filters through the hide walls of the tipi, casting all in a kind of golden hue. “We came here a year ago,” Susie begins, “under the same program as you. We were with the first group of women sent out to marry among the Cheyenne. And so we did. And now as you may also have guessed from the look of us, we have gone over to the other side. We are white Cheyenne. We come here to help you. We know you been through a terrible ordeal. We know you’re tired and scared. We been there, too, believe me. But the first thing you must learn is that whinin’ and behavin’ like sissies will gain you nothing from these people but scorn and abuse. They do not respect weakness, nor do we. Now which of you be the leader among you?”

“What do you mean by the leader?” ventures a timid girl seated beside me in a wee Liverpudlian voice. “We are all of us just prisoners.”

“Aye, but in every group like this,” says I, “there is usually one who takes charge … at least until such time as everyone else gets their feet under them, so to speak. Let us put it this way, then, who is the one you look to first in a tough spot? Ours was a lass by the name of May Dodd. She didn’t ask for the job, just kinda fell into it. So whoever that be among you, go ahead and introduce yourself.”

Me and Susie could tell right away by the number of girls who all looked over at one particular girl on the other side of the circle that she was the top dog alright. She seemed reluctant and a wee embarrassed to claim the title, but finally she stood up. She was a handsome lass, maybe a few years older than some of the others, tall, big-boned, a blue-eyed fair-haired lass who looked like she knew how to take care of herself.

“I don’t know why,” she said, “but for now I guess that might be me.”

“Alright, that’s a fine start,” says Susie. “And what would your name be then, lassie?”

“Molly. Molly McGill.”

“Aye, a good Scottish name. Where do you come from, Molly McGill?”

“It’s true that my family was of Scottish origin,” she says. “We had a farm in northern New York, up near the Canadian border not far from Champlain. However, I was living in New York City.”

“What kind of work did you do in New York City?”

“I was a schoolteacher and a charity worker. I worked mostly with children without homes.”

“That had to be a hard work.”

“Hard enough. Will all the immigrants arriving, there are so many of them.”

“Susie and me been there, too…” says I, “we grew up in an orphan asylum in the Chicago tenements, farmed out to different foster families who mostly took us right back soon as they could because we were a pack a’ trouble, we Kelly twins. We could not bear to be separated and when we were we tried to run away first chance we got. Finally they said we were unadoptable and locked us up in one a’ the orphan asylums reserved for repeat runaways. But we ran away from there, too. We spent a lot of time livin’ on the streets. So you see, we know a bit about such matters and we know you must be a tough lass to work that kinda job.”

Molly McGill shrugs. “Not always tough enough.”

“Ain’t that always the way, though?”

“And you must be smart to be a teacher,” says Susie. “Meggie and me admire those that know something more than the mean things we learned growing up. The only useful talent we came away with was how to take care of ourselves. You look like a girl who knows how to do that, too.”

“I do what I have to do.”

“Good, then you got the job.”

“And what does that job entail?” she asks.

“Stayin’ alive, and keepin’ your friends that way, too,” says I. “That’s the first responsibility. You’ll soon find out, if you haven’t already, it’s full-time work in this country among these folks.”

Molly looks us hard in the eyes for a long moment. We get the sense that this is a girl who has known some considerable trials in her life. “That we have already learned,” she says, finally. “And how did your friend May Dodd do in the performance of this duty?”

“She did just fine for a long time,” says I. “And then in two shakes of a lamb’s tail not so fine. She didn’t make it … through no fault of her own.”

“I’m awfully sorry to hear that,” says Molly McGill. “What happened to her?”

“All a’ that in good time, missy,” says I. “Right now, it’s we who want to get to know about you. First off, there being only seven of you, we’re curious … How many did you start out with?”

“We were a total of nineteen when we boarded in Chicago,” says Molly. “By the time we reached Omaha, four women had had second thoughts and jumped train at various stops along the way. We lost two more in Omaha for the same reason … and six of our party were killed when the Lakota attacked the train … God rest their souls.” Some of the girls started to get teary again at this fresh memory, and maybe at the reminder of their fast-dwindling number.

“We’re real sorry about that,” says Susie. “If your group was anything like ours, we know you made friends fast on the trip out. We know how it is to lose friends.”

“Why don’t you begin for us, Molly,” says I to get off the subject quick as possible. “How is that you came to sign up for the program?”

“To gain parole from Sing Sing prison,” she answers.

“Did you now?” says I. “And what were ya in for, if we may ask?”

“Murder.”

“Who’d ya kill, then?” asks Susie.

“A man who deserved it. But I cannot speak further of that.”

“Aye, that’s fine, lass,” says I. “We are none of us required to say any more than we choose, and all have a right to guard our secrets. That’s how it was among our group.”

“Meggie and me has been in stir ourselves,” says Susie. “I imagine being cooped up in this tipi might remind you a bit of that.”

“As a matter of fact, as I have been telling the girls, this place is preferable to Sing Sing. The prisoners there aren’t allowed to speak. Ever. Not a word. Absolute silence is the rule. And if we were caught at it, we were whipped, beaten … or worse. I was not what you would call a model prisoner. I was considered an agitator, and I spent a good deal of time in solitary confinement. When the recruiter for the brides program came, the warden was delighted to be rid of me. And I was ready to go anywhere. Anywhere. For me, compared to that place, this is a stroll in Central Park on a Sunday afternoon. Even the food is better.”

“Brilliant,” says I, “excellent start, we’ve got a murderer among us. Have we a lunatic or two?”

Now another woman in the circle raises her hand. She stands, brushes herself off, clears her throat. A manly-lookin’ bird, tough and built like a spool of wire, she has short cropped hair, wears jodhpurs and fancy English riding boots. “I hope I do not disappoint you ladies,” she says in a hoity-toity British accent, “when I tell you that I am neither a criminal, nor am I insane. If I may present myself: I am Lady Ann Hall of Sunderland.” Susie and me exchange a glance then, because this is a name we have heard before. “And the young lady here beside me,” continues the Englishwoman, indicating the girl who sat at her feet, “is my maidservant, Hannah Alford from Liverpool. Raise your hand, Hannah.” The tiny slip of a girl, timid as a mouse, raises her hand.

“You won’t have much use for a servant here, m’lady,” says Susie. “Like May Dodd said at the beginning of our own journey, you’ll soon find out that you are all equal here, regardless of where you come from, who your family was, what you did in your past lives, how much money you got, how much education, your accent or the color of your skin. Because you see, you’ll learn real quick if you haven’t already that none of that matters in this country.”

“Quite the contrary,” says Lady Ann Hall. “I believe that even in the wilderness, it is essential to observe civilized social hierarchy and conventions. I consider myself no less a lady here than back in Great Britain.”

“That’s all very well, m’lady,” says I. “But out here it’s the Indians who decide the hierarchy and conventions, and, believe it or not, they really don’t give a rat’s arse about British titles. In fact, you’ll be lucky not to be workin’ as a maidservant yourself in the household of a Lakota squaw.”

“Not bloody likely,” says Lady Hall. “You see, in addition to my title, I served for three years as the president of the London National Society for Women’s Suffrage. I lead women, I do not follow, nor, I can assure you, do I do housework.”

“Well, then, do tell us how you joined the program, Lady Hall.”

“I have come here in search of my companion,” says she, “the ornithologist and artist Helen Elizabeth Flight. I received one short letter from her posted from Fort Laramie almost a full year ago. She told me of her enrollment in the Brides for Indians program, and a little about the group with whom she had been dispatched, of which I must assume you ladies were also members. After that, I had no further word from her. I attempted to make inquiries of the authorities in America via representatives of my own government, but to no avail. It seemed, finally, that the only hope I had of finding her was to come out here as a volunteer myself. You ladies must have known Helen. Can you give me news of her?”

Susie and me look at each other again, our memory well refreshed as to where we had heard Lady Hall’s name. “Indeed we can, m’lady,” says I. “Helen Flight is a dear, dear friend of ours. We shall tell you later, in private, all we know of her.”

“Ah, splendid news,” says Lady Ann Hall, “then I am on her trail, after all. A stroke of good fortune to have come across you ladies. Thank you.”

We do not wish to disabuse the Englishwoman of this notion just yet, and neither me nor Susie says anything further about Helen. But a shadow crosses our hearts at the prospect of having to tell her the truth of what happened to our dear brave friend who fought the soldiers to the end.

“Alright, then,” says Susie. “Now, we brought you girls a wee gift, a stack of these ledger books and some colored pencils. As the leader, we’re givin ’em to you, Molly, to distribute as you please.”

“For what reason do we need ledger books?” she asks. “Are the Lakota going to put us to work keeping their accounts?”

Susie and me laugh. It is already clear to us that this Molly McGill is a direct girl, not afraid to speak her mind. “See, we don’t have much to offer,” says I, “but we came into a nice stash of these when we got here. All the tribes have artists among them, who trade hides for the books at the white trading posts, and use ’em to draw pictures on. Helen Flight calls their work ‘primitive’ because you see they paint everything real flat, without ‘perspective,’ she says. But we all liked it anyhow, even Helen, and she taught them a few of her own tricks. Now if you don’t want to draw on ’em, you can do like me and Susie, and our friend May did, and use ’em to keep a diary. Either way, we thought it’d give you girls somethin’ to do besides worry yourselves sick all day long.”

“I kept a diary myself on the train,” says Molly. “But like all our other possessions, it is lost now. Needless to say, our abductors did not allow us to bring along our bags. We are grateful to have this paper and pencils. Of course, we will share them.”

Now Susie points to a pretty young girl sitting cross-legged in the first row, her head downcast. “And you there, darlin’?” she says. “Speak up, tell us your name and how you came to be here. Don’t be shy.”

She looks up, smiles real friendly. “But I am not shy,” she says, speaking with a French accent. “My name is Lulu LaRue. That is my stage name, and that is what I call myself, for I am an actress. I sing and I dance.” One or two of the other girls snicker at this.

“Aye, in the theater then, are you? And where are you from, Lulu LaRue?”

“I come from Marseille, France,” she says, “and from there I go to Los Angeles, California.”

“And what brought you to the program?”

“I go to Los Angeles with other women from France to work in a laundry,” she says. “It is very hard work and the hours are long and we are hardly given a day of rest. When one of those days arrive, I look for work in the theater. But you see, my English is not so strong and no one has interest in a little French girl with funny accent. One day I answer advertisement to try out for a theater group from St. Louis, Missouri. The man who auditions me is very handsome, charming, very kind with me. His name is Earl Walton. He ask me if I know how to dance. Mais oui, I say, of course, I dance, I am very good dancer. And so for him I do a French dance called the cancan. He say he like me, he like the way I dance, and he want to give me a job in his theater. He ask my address and say he will be in contact. The very next day, he come to our rooming house. He say that he must leave Los Angeles immédiatement, and go back to St. Louis, that if I want the job in his theater, I must go with him now. He does not give me time to think … it sounds so exciting, and I am glad to leave the laundry. And so that same afternoon, I go with him. It is a very long trip to St. Louis, very hard. This man Earl is all I have in the world … I begin to fall in love with him … at least I think I am in love. He say he love me, too, and that after we arrive we will marry together.”

“I think we’re beginning to get the picture, Lulu,” says Susie. “So tell us about this theater in St. Louis.”

“Well, you see … it is not really a theater at all,” says Lulu. “Earl is the proprietor of a private gentlemen’s club. There the girls dance and sometimes put on shows to entertain the gentlemen … and, of course, they must do other … certain other service.”

“Aye, say no more, Lulu,” says Susie, holding up her hand. “Meggie and me has taken similar employment in times of need. And so you signed up for the brides program in order to escape this Earl fella, is that how it happened?”

“Oui … you see, it become clear that the only reason he hire me is so I learn the others to dance the cancan. He is not going to marry me, he does not love me … I think he not even like me … the other girls say he make the same promise to them. We are prisoners at the club. We are not allowed to leave there, not even to go shopping, unless one of his men is with us. When I finally escape, I know that I must go as far away from St. Louis as possible, or Earl find me and bring me back.”

“In that case, lassie,” says I, “lookin’ on the bright side, you have come to the right place. Earl won’t be finding you here in Crazy Horse’s camp, that is for certain.”

“Yes, well I always try to look on the bright side,” says Lulu LaRue. “I was even thinking life as the wife of a Cheyenne Indian will make bigger my palette … no, wait, how do you say?… make bigger my range as an actress.”

“Quite possible, Lulu,” says Susie, “for one never knows when learning to fook Indian style will come in handy on stage.” At this some of the other girls giggle nervously, both shocked and amused at our language.

“There, you see, ladies,” says I, “one thing our group learned in our time out here is that a little laughter goes a long way toward lightening the dark times. We know you don’t feel like it most of the time, but it’s the only way to keep your spirits up, the only way to survive. We were all the time makin’ fun and teasin’ each other. You’ll find that the Indians themselves have a sly sense of humor if you can engage them on that level. The truth is, Lulu, I’ll wager your acting skills will serve you well here.”

“Do you have any idea what the Lakota plan to do with us?” asks Molly. “Are they going to keep us prisoner indefinitely?”

“That’s what we’re gonna try to find out,” says I.

“Will they give us to the Cheyenne?” asks another girl, who seems to have a Scandinavian look and accent about her. “It is to them we are to be married. To help keep the peace on the Great Plains, to teach the savages the civilized ways of the white man.”

“Aye, aye,” says I, “we know all about the civilized ways of the white man. Brother Anthony didn’t tell you lasses much, did he? He wanted to leave that to us. We are sorry to inform you of it, but you are not going to be the brides of Cheyenne warriors. The program has been ended and most of the Cheyenne are surrendering. Nor is the Army or your government going to come to your rescue as you must be hopin’. To them, you see, the Brides for Indians program never existed, and they wish now to bury all evidence of it.”

“And what exactly do you mean by ‘bury’?” asks Lady Ann Hall. “Where are the rest of the women in your group now?”

“We’ll get to that in good time, m’lady,” says Susie. “Right now, we just want you to understand that you’re on your own out here. You have only yourselves and each other to count on. No one is coming to save you, and that is something you’d best get used to right off.”

“For whatever wee consolation it may bring you,” says I, “you also have us … for now anyhow. First thing we’re going to do is try to powwow with the Lakota chiefs and see if we can’t figure out a way to get you out of here.”

Susie and me were hoping maybe we could slip out of the girls’ tipi quick like without having a private conversation with Lady Hall about Helen just yet. However, she asks to step outside with us, and when we do, she comes right to the point. “My dearest companion Helen is dead, is she not?”

Susie and me look long at each other, neither wishing to be the one to say, as if telling of it is like a second death for Helen … and for us. “Yes, m’lady, she is,” I answer at last. “How did you know?”

“It was quite obvious from the looks on your faces when first I spoke of her,” says the Englishwoman. “However, I pretended not to notice for I was afraid I might fall apart in front of the others. I do not grieve publicly.”

“You are a strong woman, Lady Hall,” says Susie. “As was Helen. We loved her … all of us did. We are very sorry for you.”

“Please tell me how she died. Tell me everything you know, and do not try to shield me from the truth.”

“She died like a grand heroine, m’lady,” says I. “The reason we have not told your group what happened to us yet is because it will only scare ’em worse than they already are. So please keep this to yourself for now. Several weeks ago the Army attacked our village at dawn. Helen stepped out of her tipi with her scattergun to defend against the invaders, while the women and children tried to escape. We were fleeing past her tipi with our babies. Helen had her corncob pipe in the corner of her mouth and she was firing at the charging soldiers. She blasted two of them right out of their saddles. As she paused to reload, she saw us running. ‘A right and a left double, girls!’ she called out to us. ‘Lord Ripon would be envious! Run! Save the children! I’ve got you covered!’

That was the last we would ever see of our dear friend Helen. After the attack was over, Brother Anthony, who stayed bravely in the village himself, came upon her body. She had been slashed across the neck by a saber, and a bullet had pierced her forehead. A soldier lay dead beside her, one side of his skull caved in. The stock of Helen’s scattergun lay broken. Anthony thinks she must have been reloading as the soldier charged her. As he swung his saber, she swung the stock of her gun, hitting him a blow to the head that unseated him from his horse. Another soldier must have finished her off with a bullet.”

Lady Hall nods. “Yes, doesn’t that sound just like my Helen? She was a tenacious girl. She would not have gone easily.” We see the tears beginning to cloud the Englishwoman’s eyes, but she keeps talking as if to avoid breaking down completely. “Helen, as you probably know, was a wonderful shot. She is the only woman who has ever been allowed to carry a gun at the grand driven shoot at Holkam Hall, Lord Leicester’s estate in Norfolk, or at any other estate shoot for that matter. She outshot all of the men that day, including Lord Ripon, who is widely considered the finest wing shot in all of England. Indeed, after her magnificent performance, Helen was never again invited to participate in an estate shoot. Evidently the men could not tolerate being outshot by a woman, and wished to ensure that it did not happen again.”

“She was a bleedin’ fine artist, too,” says Susie. “The Cheyenne warriors felt she possessed big medicine. Before they went off on raids, they had her paint animal and bird images on their bodies, and on their horses, too. They believe these protect them in battle. Last summer and fall, they returned victorious from every raid, and the warriors credited Helen’s artistic skills for their success. She became quite famous among the tribe.”

“Thank you for telling me this,” says Lady Hall. “It means a great deal to me. I should like to know if any of her work on the birds of the western prairies survived?”

“Not that we know of,” says I. “After the attack, the soldiers burned everything in the village. It is not likely that Helen’s sketchbooks were spared from the flames.”

19 March 1876

Well, goddamned if she didn’t ride right into the village this afternoon, astride a big gray mule, head held high like she owned the place, like a conquerin’ hero come home. Aye, our old friend Dirty Gertie, aka Jimmy the muleskinner. She must somehow have slipped past the Lakota sentries, which, believe us, is no easy thing to do, unless you be Indian yourself. For her to appear like that, alone and without warning, was a serious deviation from the normal way of things, and her entrance caused considerable consternation in the village. The people came out of their tipis to watch silent and with a sense of wonder as she rode by. No one molested her, nor did the children run out to count coup on her as they liked to do. As if taking their cue from the behavior of the adults, they stood real close together, hugging the legs of their parents or older brothers and sisters, quiet and watching round-eyed as Gertie made her way through the village, now and then touching the grimy brim of her hat in friendly greeting to those she passed on either side.

Aye, they knew who she was, pretty much everyone on the plains, Indian and white alike, knows Dirty Gertie. But like us, they’d heard she was dead, killed by the half-breed Jules Seminole and his band of Crow scouts. Such news travels fast out here, for Gertie was well-liked by the Cheyenne and the Lakota, having herself lived among these tribes. She’s been in this country for years, got captured off a wagon train as a girl, married young the first time to a French trapper, who traded her for her weight in hides to the Southern Cheyenne, with whom she lived for a number of years, married a Cheyenne fella. Since then Gertie has moved easily between the Indian and white worlds; she’s scouted and driven mule trains for the Army, served as an informer to the Indians, been shot, knifed, and left for dead by both sides. You name it, Gertie has seen and done it all, and no one, Indian or white alike, seems to hold it against her. She’s just that kind of person who gets a pass from both sides, maybe because they know she does the right thing. So everyone took it real hard when they heard that the murderous scoundrel Seminole, who was hated as much as Gertie was loved, had done her in. Now as she rode through Crazy Horse’s camp, the people wondered if they were seeing a ghost, because everyone believed she was dead.

But me and Susie don’t believe in ghosts and I cannot say how happy we were to see her. Unlike the Lakota who just watched her silently as she passed, as soon as we parted the tipi flap to see who was clip-cloppin’ by and we recognized Gertie—dressed in her familiar fringed buckskins she hardly ever changed out of, her braided hair startin’ to go gray, her face as leathery brown, beat-up, and wrinkled as an old boot—we come out at a dead run to her. With a whoop I swung up on the mule’s withers facing her, and Susie jumped on his back behind her, and we both gave her big hugs, kind of a twin sandwich. “Goddammit all, Gertie, they said you were dead!”

“I ain’t dead yet, but if you two Irish scamps don’t stop squeezin’ the damn wind outta me, I will be soon.”

“We heard Jules Seminole killed you.”

“Son of a bitch give it a real good try,” she says. “Invite me in for a cup a’ coffee, girls, and I’ll tell you the whole story.”

And so Gertie picketed her mule outside our tipi, and we sent the horse boy to bring a pile of dried grass for him to chew on. We boiled up some coffee in the tipi and when we all got settled, Susie asked: “What are you doing here, Gertie? You didn’t seem surprised to see us. Did you know we were here?”

“I was at Camp Robinson when Little Wolf brought his people in to surrender,” she says. “Brother Anthony told me you gals had stayed out with Crazy Horse.”

“But how did you ever find us?”

“Aw hell, girls, I know this Powder River country blindfolded, you oughta know that by now. It weren’t hard at all for ole Dirty Gertie to find ya.”

“Then you know what happened to us down on the Tongue…” says I.

Gertie gazes into the fire, tears rising into the corners of her bright green eyes, peering out beneath hooded lids and sparkling wet now in the flickering flames. We never seen Gertie cry before. We didn’t even know the tough old bird was capable of it. “Yeah … I know all about that,” she says in a low voice. “Broke my friggin’ heart when I heard. And it was all my damn fault, too. After that last visit I made to your village, I was on my way back to the fort to deliver May’s message to Cap’n Bourke. She wanted to tell him where you was located, and that Little Wolf had decided to come into the agency as soon as the weather cleared and it was safe to travel with the newborns. But Seminole had it in for you folks, and he didn’t want that message delivered. So he and his Crow scouts were layin’ for me on the trail, shot me the hell fulla arrows, until I looked like one a’ them damn voodoo dolls they poke needles into. Left me out there for dead. If it hadn’t been for a coupla Arapaho braves who come upon me and took me back to their village, the coyotes and the buzzards woulda been shittin’ me out for a week. As it was, I was laid up a good long time, touch and go. If I’d a’ made it back, you’d a’ never been attacked. It was that goddamned Jules Seminole who guided the cavalry to you, who told Colonel Mackenzie it was Crazy Horse’s camp, not Little Wolf’s. It was all on account a’ that half-breed bastard all this has come to pass.”

“Where is Seminole now?”

“They tell me he’s livin’ with the Crow,” Gertie says. “Right after the attack against you folks, General Crook called off the winter campaign on account a’ the cold weather. Too many soldiers was gettin’ frostbit, losin’ fingers and toes. That’s why they haven’t found this village yet. But if spring comes on early, like it’s maybe fixin’ to do, the Army’ll be on the move again real soon, and the Injun scouts will be back hangin’ around the fort lookin’ for work … When the bastard shows his face, I’ll be ready for him, that I can promise ya.”

“But why would the Army use Seminole to scout for them again,” asks Susie, “if they know now that he led them to the wrong village?”

“Hell, girl, you oughta know by now that the Army don’t give a damn they wiped out Little Wolf’s village ’stead of Crazy Horse’s. It’s still just one less band of renegades for ’em to deal with, either way. Sure, they lost some white women in the bargain, but the newspapers don’t even knew about you gals anyhow, so no one is the wiser. As to the babies they killed…” Gertie pauses here and tears up again. “Damn, I’m gettin’ soft in my old age, ain’t I,” she whispers as if to herself.

“Brother Anthony told me what happened to your little girls,” says Gertie after she collects herself. “I’m real sorry for you. I think you know I was with the Southern Cheyenne at Sand Creek in sixty-four when Chivington’s troops attacked our village. Our head chief, Black Kettle, wanted peace, he was flying an American flag from his tipi that day to show his loyalty. But Chivington ordered the attack anyhow. An’ before he did, he told his soldiers, ‘Kill and scalp them all, big and little, nits make lice.’ See, that’s how highly they think of the Injuns, that they ain’t even human beings, they’re insects … nits and lice…”

Gertie stops here and gazes long into the fire. “The soldiers killed my two babies by my Cheyenne husband that day,” she whispers finally. “I never told that part to May, I never told her I had kids, didn’t want to scare her, her being a new mother and all. I took three bullets in the attack and the soldiers musta thought I was dead. But I wasn’t and when I come to, I was lyin’ under a pile a’ bodies. Maybe on account a’ the fact I was at the bottom, they hadn’t bothered to take my scalp. But I was hurt real bad and I didn’t even have the strength to crawl out from under. The soldiers were still sacking the village, rapin’ our girls, killin’ the wounded. Then I saw my little boy, Hóma’ke I called him … Little Beaver … five years old he was … he was cryin’ and wanderin’ around a ways off. He was lookin’ for me, see? He was scared and lookin’ for his mama … Two soldiers standin’ not too far from me, spotted him, and they pulled their pistols. They were laughin’, an’ bettin’ each other and they started takin’ turns shootin’ at him … I could see their bullets hittin’ the ground all around him, I tried to holler, I tried to scream, but no sound came out, and my little boy just kept walkin’, cryin’ … lookin’ for his mama … and then I saw my little girl, Little Skunk we called her, Xaóhkéso … she was runnin’ toward him … she was seven an’ she always took care of her little brother … I tried to scream, I tried to holler, but no sound came outta my mouth an’ I couldn’t crawl out from under the bodies. Just before Little Skunk got to him, one a’ the bullets struck her in the back and she went down … and the soldier who shot her hollered to the other, ‘You owe me a nickel, you sumbitch’ … and that’s the last thing I remember … ‘You owe me a nickel, you sumbitch.’

“I don’t know how long I was out, but when I woke up the soldiers were gone, and the village was quiet. It took me some time but I finally managed to drag myself out from under the bodies and I crawled on my belly through the burnt ruins of the village until I found my babies … both of ’em dead … scalped … yeah … nits make lice … an’ you know what else? That Colonel Chivington was a preacher … that’s right, the Denver newspapers called him the Fightin’ Parson, a man of God. I tell you all this now, girls, so you understand that I know firsthand a little something about what you been through … it breaks my friggin’ heart … I am so sorry for you…”

And then we all had a good long cry. The three of us, me and Susie and Gertie, held on to each other and we bawled like babies. It was the first time me and Susie had been able to cry for our daughters, and for our friends lost.

21 March 1876

Brother Anthony had told Gertie about the new group of white women here. Aye, that’s another reason she came to us, she says, figuring we could maybe use a little help with the situation. She was sure right about that, because when me and Susie tried to set up a powwow with Crazy Horse and the other chiefs we were told that they do not council with women. We shoulda known that because it’s the same with the Cheyenne, too. Even though women have considerable influence in the tribe … in fact, they can be said to run the show from the background, they are still not allowed to participate in council. For that matter it’s the same with the U.S. government, ain’t it? We aren’t even allowed to vote. And why do you suppose it is that these very different societies have this in common? I’ll tell you why, it’s because the old men who make the decisions for everyone else don’t have the same amount of man juice runnin’ through their veins anymore, only the fadin’ memory of it, so they use the young men to stand in for their own shriveled bollocks and limp weenies. But mothers don’t want to send their babies off to war, and the old men know that if they allow women a voice in council, they will only get in the way of all their war plans. It’s as simple as that.

But for some reason me and Susie couldn’t figure out until she explained it to us later, the Lakota chiefs were willing to council with Gertie. We were allowed to attend, and bring Molly along, but were not allowed to speak. Gertie knows the Lakota language, too, so we didn’t even need a translator. We love our Gertie and don’t hold it against her in any way, but she can be rough as a bear’s arse, and often smells like one, and it’s true that despite her soft side, she’s got a manly way about her—walks like a man, cusses like a man, dresses like a man … about the only thing she doesn’t do is piss like a man, which is how she got found out by May, when we all still thought she was Jimmy the muleskinner.

Now when it’s Gertie’s turn to speak, one of the chiefs, who she tells us is named Rides Buffalo, passes her the pipe. She takes a long pull on it, which makes me and Susie a wee bit envious, because we enjoy a smoke now and again ourselves. Then Gertie starts talkin’ and she goes on at some length, but of course, we understand nothing of what she says. We can see that the chiefs listen to her very respectful as she speaks. She finishes with what seems like a fancy flourish of language, and passes the pipe with some pomp and fanfare to the chief on the other side of her. Like the Cheyenne, these men do love to talk, and each goes on at some length when it’s their turn, all except for Crazy Horse, that is, who says only a few words, but seems to listen thoughtfully to everyone else.

It’s useful havin’ Molly there with us. She’s real alert and pays attention and it’s clear that she makes a favorable impression on the chiefs. She’s a fine thing, a statuesque lassie with a real presence about her. She appears not to be at all intimidated by these men, who can be a wee bit scary truth be told, and they in turn seem to admire both her appearance and the bold, direct manner she has about her.

After the powwow finally concludes, we want Gertie to give us a full account of how things went with the chiefs before we inform the other girls. So the four of us go down and sit on the banks of the creek, which is still mostly covered with ice, except for the water holes kept open.

“No decision has been reached yet by the chiefs,” Gertie begins. “It’s always like that with these folks, they like to mull things over for good long while. I gave ’em a lot to think about, told ’em something I haven’t even told you gals yet. About ten days after Little Wolf surrendered his band at the Red Cloud Agency, they left again. The chief could not tolerate life there, with no game to hunt and nothing to do all day long, eatin’ outta tin cans what little food rations was given to ’em by the government. So they made a run for it. You Kelly girls know as well as I that no one can sneak off as quiet as a band of Indians when they set their mind to it, you and me have seen ’em do it, ain’t we? They don’t move like white people, who make a lotta noise even when they’re trying not to, they move like the wind, like a light breeze in the air, with only the faintest rustling no more noticeable or unnatural than that made by the movement of spirits. By the time the Army figured out what had happened, they were well on their way.”

“Where did they go, Gertie?” I ask.

She shrugs. “Who knows? I expect Little Wolf took ’em north, lookin’ for open country and some buffalo herds, maybe trying to hook up with another band or two of Cheyenne who ain’t surrendered yet.”

“And why did Crazy Horse and the chiefs need to know that?” Susie asks.

Now this is what surprised me and Susie, and when Gertie said it we realized that she really has gone over to the other side: “I told Crazy Horse the Army was plannin’ another major military campaign against the Lakota and all the other scattered bands that hadn’t observed General Crook’s order to surrender. I told ’em more soldiers were headed out here from the East, more horses, more guns and supplies. I said that the Cheyenne and the Lakota had long been strong allies, and that Little Wolf and Crazy Horse were the two greatest warriors and leaders of their people. I said the only hope they had against the Army was to put aside whatever differences were between ’em, join forces and fight together. Then I asked that the Lakota give up a dozen of the horses they stole off the train, and let the white women go. And I finished up by sayin’: ‘Now I have spoken true what is in my heart. I have told you what I know about the movements of the Army, and I have told you what I believe is good for your people and good for these women. I thank you for hearing me.’ See, the chiefs like it when you speak to ’em real respectful and formal like that. I give ’em valuable inside information and I ask for the horses in return without really having to say it’s tit for tat, cause everyone already understands how these things work.”

Now me and Susie thought it was one thing for Gertie to be offered the pipe, and make a case for releasing the women in her custody, and something else altogether for her to be givin’ war counsel to the Lakota chiefs. What we learned in our time among the Cheyenne was that the best way for us to address the men with any kind of advice was real indirect, what May called “by allusion,” which was too fancy a word for me and Susie, but means kind of a way of hinting that allows ’em to think maybe they came up with the idea themselves. We found it was never a good idea to come right out and tell them what they should do because men almost always take offense to that.

“But how is it, Gertie,” I ask, “that as a woman you can speak so frank that way to the chiefs? Even though we couldn’t understand ’em, we could see that they were listening real close to everything you said.”

“Aw hell,” she answers, “don’t you gals know?… both the Cheyenne and the Lakota consider me to be a he’emnane’e—half-man, half-woman. See, everyone knows I was married to a Cheyenne fella and had babies by him. And they also know I ran a mule train for years as a boy named Jimmy. They believe the he’emnane’e have big medicine, that we have all the qualities, wisdom, and power of both sexes … which … what the hell, might even be true. That’s why they pass me the pipe, which gives me the right to speak my mind in council. And because I can speak as a man, I have some legitimate influence. Course, even though I don’t have all the necessary body parts to qualify me as a real he’emnane’e, I have never tried to disabuse the tribes of that notion, because it’s real useful to be treated as both man and woman if you get what I mean. On the one hand, they gotta behave toward me with a certain kinda manners they reserve for women, on the other I have the full voice of a man. Comes in mighty handy sometimes.”

“Aye, such as right now, Gertie/Jimmy the muleskinner,” says I. And we laugh.

Copyright © 2017 by Jim Fergus

The Vengeance of Mothers: The Journals of Margaret Kelly & Molly McGill

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 368 pages

- Publisher: St. Martin's Griffin

- ISBN-10: 1250093430

- ISBN-13: 9781250093431