Excerpt

Excerpt

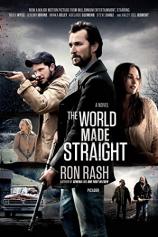

The World Made Straight

Chapter One

Travis came upon the marijuana plants while fishing Caney Creek. It was a Saturday, the first week of August, and after helping his father sucker tobacco all morning he’d had the rest of the day for himself. He’d changed into his fishing clothes and driven three miles of dirt road to the French Broad. Travis drove fast, the rod and reel clattering in the truck bed, red dust rising in his wake. The Marlin .22 slid on its makeshift gun rack with each hard curve. He had the windows down, and if the radio worked he would have had it blasting. The truck was a ’66 Ford, battered from a dozen years of farm use. Travis had paid a neighbor five hundred dollars for it three months earlier.

He parked by the bridge and walked upriver toward where Caney Creek entered. Afternoon light slanted over Divide Mountain and tinged the water the deep gold of curing tobacco. A fish leaped in the shallows, but Travis’s spinning rod was broken down and even if it hadn’t been he wouldn’t have bothered to cast. Nothing swam in the French Broad he could sell, only hatchery-bred rainbows and browns, some smallmouth, and catfish. The old men who fished the river stayed in one place for hours, motionless as the stumps and rocks they sat on. Travis liked to keep moving, and he fished where even the younger fishermen wouldn’t go.

In forty minutes he was half a mile up Caney Creek, the rod still in two pieces. There were trout in this lower section, browns and rainbows that had worked their way up from the river, but Old Man Jenkins would not buy them. The gorge narrowed to a thirty-foot wall of water and rock, below it the creek’s deepest pool. This was the place where everyone else turned back, but Travis waded through waist-high water to reach the waterfall’s right side. Then he began climbing, the rod clasped in his left palm as his fingers used juts and fissures for leverage and resting places.

When he got to the top he fitted the rod sections together and threaded monofilament through the guides. He was about to tie on the silver Panther Martin spinner when a tapping began above him. Travis spotted the yellowhammer thirty feet up in the hickory and immediately wished he had his .22 with him. He scanned the woods for a dead tree or old fence post where the bird’s nest might be. A flytier in Marshall paid two dollars if you brought him a yellowhammer or wood duck, a nickel for a single good feather, and Travis needed every dollar and nickel he could get if he was going to get his truck insurance paid this month.

The only fish this far up were what fishing books and magazines called brook trout, though Travis had never heard Old Man Jenkins or anyone else call them a name other than speckled trout. Jenkins swore they tasted better than any brown or rainbow and paid Travis fifty cents apiece no matter how small. Old Man Jenkins ate them head and all, like sardines.

Mountain laurel slapped his face and arms, and he scraped his hands and elbows climbing rocks there was no other way around. Water was the only path now. Travis thought of his daddy back at the farmhouse and smiled. The old man had told him never to fish places like this alone, because a broken leg or rattlesnake bite could get a body graveyard dead before someone found you. That was about the only kind of talk he’d ever heard from the old man, Travis thought as he tested his knot, always being put down about something—how fast he drove, who he hung out with. Nothing but a bother from the day he was born. Puny and sickly as a baby and nothing but trouble since. That’s what his father had said to his junior high principal, like it was Travis’s fault he wasn’t stout as his daddy, and like the old man hadn’t raised all sorts of hell when he himself was young.

The only places with enough water to hold fish were the pools, some no bigger than a washtub. Travis flicked the spinner into the front of each pool and reeled soon as it hit the surface, the spinner moving through the water like a slow bright bullet. In every third or fourth pool a small orange-finned trout came flopping onto the bank, treble hook snagged in its mouth. Travis slapped the speckleds’ heads against a rock and felt the fish shudder in his hand and die. If he missed a strike, he cast again into the same pool. Unlike brown and rainbows, speckleds would hit twice, sometimes even three times. Old Man Jenkins had said when he was a boy most every stream in Madison County was thick as gnats with speckleds, but they’d been too easy caught and soon fished out, which was why now you had to go to the back of beyond to find them.

eight trout weighted the back of his fishing vest when Travis passed the no trespassing sign nailed aslant a pin oak tree. The sign was as scabbed with rust as the decade-old car tag nailed on his family’s barn, and he paid it no more heed now than when he’d first seen it a month ago. He knew he was on Toomey land, and he knew the stories. How Carlton Toomey once used his thumb to gouge a man’s eye out in a bar fight and another time opened a man’s face from ear to mouth with a broken beer bottle. Stories about events Travis’s daddy had witnessed before he’d got right with the Lord. But Travis had heard other things. About how Carlton Toomey and his son were too lazy and hard-drinking to hold steady jobs. Travis’s daddy claimed the Toomeys poached bears on national forest land. They cut off the paws and gutted out the gallbladders because folks in China paid good money to make potions from them. The Toomeys left the meat to rot, too sorry even to cut a few hams off the bears’ flanks. Anybody that trifling wouldn’t bother walking the hundred yards between farmhouse and creek to watch for trespassers.

Travis waded on upstream, going farther than he’d ever been before. He caught more speckleds, and soon seven dollars’ worth bulged the back of his fishing vest. Enough money for gas and to help pay his insurance, and though it wasn’t near the money he’d been making at Pay-Lo bagging groceries, at least he could do this alone, not fussed at by some old hag of a store manager with nothing better to do than watch his every move, then fire him just because he was late a few times.

He came to where the creek forked and it was there he saw a sudden high greening a few yards above him on the left. He stepped from the water and climbed the bank to make sure it was what he thought. The plants were staked like tomatoes and set in rows like tobacco or corn. They were worth money, a lot of money, because Travis knew how much his friend Shank paid for an ounce of good pot and this wasn’t ounces but pounds.

He heard something behind him and turned, ready to drop the rod and reel and make a run for it. On the other side of the creek a gray squirrel scrambled up the thick bark of a blackjack oak. Travis told himself there was no reason to get all feather-legged, that nobody would have seen him coming up the creek.

He let his eyes scan what lay beyond the plants. A woodshed concealed the marijuana from anyone at the farmhouse or the dirt drive that petered out at the porch steps. Animal hides stalled mid-climb on the shed’s graying boards. Coon and fox, in the center a bear, their limbs spread as though even in death they were still trying to escape. Nailed up there like a warning, Travis thought.

He looked past the shed and didn’t see anything moving, not even a cow or chicken. Nothing but some open ground and then a stand of tulip poplar. He rubbed a pot leaf between his finger and thumb, and it felt like money, a lot more money than he’d ever make at a grocery store. He looked around one more time before taking out his pocketknife and cutting down five plants. The stalks had a twiney toughness like rope.

That was the easy part. Dragging them a mile down the creek was a chore, especially while trying to keep the leaves and buds from being stripped off. When he got to the river he hid the marijuana in the underbrush and walked the trail to make sure no one was fishing. Then he carried the plants to the road edge, stashed them in the gully, and got the truck.

When the last plants lay in the truck bed, he wiped his face with his hand. Blood and sweat wet his palm. Travis looked in the side mirror and saw a thin red line where mountain laurel had slapped his cheek. The cut made him look tougher, more dangerous, and he wished it had slashed him deeper, enough to leave a scar. He dumped his catch into the ditch, the trout stiff and glaze-eyed. He wouldn’t be delivering Old Man Jenkins any speckleds this evening.

Travis drove home with the plants hidden under willow branches and feed sacks. He planned to stay only long enough to get a shower and put on clean clothes, but as he was about to leave his father stopped him.

“We haven’t ate yet.”

“I’ll get something in town,” Travis replied.

“No. Your momma’s fixing supper right now, and she’s got the table set for three.”

“I ain’t got time. Shank’s expecting me.”

“You’ll make time, boy,” his father said. “Else you and that truck can stay in for the evening.”

2

it was six-thirty before travis turned into the abandoned Gulf station and parked window to window beside Shank’s Plymouth Wildebeast.

“You won’t believe what I got in the back of this truck.”

Shank grinned.

“It’s not the old prune-faced bitch that fired you, is it?”

“No, this here is worth something. Get out and I’ll show you.”

They walked around to the truck bed and Shank peered in.

“I didn’t know there to be a big market for willow branches and feed sacks.”

Travis looked around to see if anyone was watching, then pulled back enough of a sack so Travis could see some leaves.

“I got five of them,” Travis said.

“Holy shit. Where’d that come from?”

“Found it when I was fishing.”

Travis pulled the sack back over the plant.

“Reckon I better start doing my fishing with you,” Shank said. “It’s for sure I been going to the wrong places.” Shank leaned against the tailgate. “What are you going to do with it? I know you ain’t about to smoke it yourself.”

“Sell it, if I can figure out who’ll buy it.”

“I bet Leonard Shuler would,” Shank said. “Probably give you good money for it too.”

“He don’t know me though. I’m not one of his potheads like you.”

“Well, we’ll just have to go and get you all introduced,” Shank said. “Let me lock my car and me and you will go pay him a visit.”

“How about we go over to Dink Shackleford’s first and get some beer.”

“Leonard’s got beer,” Shank said, “and his ain’t piss-warm like what we got last time at Dink’s.”

They drove out of Marshall, following 25 North. A pink, dreamy glow tinged the air. Rose-light evenings, Travis’s mother had called them. The carburetor coughed and gasped as the pickup struggled up High Rock Ridge. Travis figured soon enough he’d have money for a carburetor kit, maybe even get the whole damn engine rebuilt.

“You’re in for a treat, meeting Leonard,” Shank said. “There’s not another like him, leastways in this county.”

“Wasn’t he a teacher somewhere up north?”

“Yeah, but they kicked his ass out.”

“What for,” Travis asked, “taking money during homeroom for dope instead of lunch?”

Shank laughed.

“I wouldn’t put it past him, but the way I heard it he shot some fellow.”

“Kill him?”

“No, but he wasn’t trying to. If he had that man would have been dead before he hit the ground.”

“I heard tell he’s a good shot.”

“He’s way beyond good,” Shank said. “He can hit a chigger’s ass with that pistol of his.”

After a mile they turned off the blacktop and onto a dirt road. On both sides what had once been pasture sprouted with scrub pine and broom sedge. They passed a deserted farmhouse, and the road withered to no better than a logger’s skid trail. Trees thickened, a few silver-trunked river birch like slats of caught light among the darker hardwoods. The land made a deep seesaw and the woods opened into a small meadow, at the center a battered green and white trailer, its back windows painted black. Parked beside the trailer was a Buick LeSabre, front fender crumpled, rusty tailpipe held in place with a clothes hanger. Two large big-shouldered dogs scrambled out from under the trailer, barking furiously, brindle hair hackled behind their necks.

“Those damn dogs are Plott hounds,” Travis said, rolling his window up higher.

Shank laughed.

“They’re all bark and bristle,” Shank said. “Them two wouldn’t fight a tomcat, much less a bear.”

The trailer door opened and a man wearing nothing but a frayed pair of khaki shorts stepped out, his brown eyes blinking like some creature unused to light. He yelled at the dogs and they slunk back under the trailer.

The man was no taller than Travis. Blond, stringy hair touched his shoulders, something not quite a beard and not quite stubble on his face. Older than Travis had figured, at least in his mid-thirties. But it was more than the creases in the brow that told Travis this. It was the way the man’s shoulders drooped and arms hung—like taut, invisible ropes were attached to both his wrists and pulling toward the ground.

“That’s Leonard?”

“Yeah,” Shank said. “The one and only.”

“He don’t look like much.”

“Well, he’ll fool you that way. There’s a lot more to him than you’d think. Like I said, you ought to see that son-of-a-bitch shoot a gun. He shot both that yankee’s shoulders in the exact same place. They say you could of put a level on those two holes and the bubble would of stayed plumb.”

“That sounds like a crock of shit to me,” Travis said. He lit a cigarette, felt the warm smoke fill his lungs. Smoking cigarettes was the one thing his old man didn’t nag him about. Afraid it would cut into his sales profits, Travis figured.

“If you’d seen him shooting at the fair last year you’d not think so,” Shank said.

Leonard walked over to Travis’s window, but he spoke to Shank.

“Who’s this you got with you?”

“Travis Shelton.”

“Shelton,” Leonard said, pronouncing the name slowly as he looked at Travis. “You from the Laurel?”

Leonard’s eyes were a deep gray, the same color as the birds old folks called mountain witch doves. Travis had once heard the best marksmen most always had gray eyes and wondered why that might be so.

“No,” Travis said. “But my daddy grew up there.”

Leonard nodded in a manner that seemed to say he’d figured as much. He stared at Travis a few moments before speaking, as though he’d seen Travis before and was trying to haul up in his mind exactly where.

“You vouch for this guy?” Leonard asked Shank.

“Hell, yeah,” Shank said. “Me and Travis been best buddies since first grade.”

Leonard stepped back from the car.

“I got beer and pills but just a few nickel bags if you’ve come for pot,” Leonard said. “Supplies are low until people start to harvest.”

“Well, we come at a good time then.” Shank turned to Travis. “Let’s show Leonard what you brought him.”

Travis and Shank got out. Travis pulled back the branches and feed sacks.

“Where’d you get that?” Leonard asked.

“Found it,” Travis said.

“Found it, did you. And you figured finders keepers.”

“Yeah,” said Travis.

“Looks like you dragged it through every briar patch and laurel slick between here and the county line,” Leonard said.

“There’s plenty of buds left,” Shank said, lifting one of the stalks so Leonard could see it better.

“What you give me for it?” Travis asked.

Leonard lifted a stalk himself, rubbed the leaves the same way Travis had seen tobacco buyers do before the market’s opening bell rang.

“Fifty dollars.”

“You’re trying to cheat me,” Travis said. “I’ll find somebody else to buy it.”

As soon as he spoke he wished he hadn’t. Travis was about to say that he reckoned fifty dollars would be fine but Leonard spoke first.

“I’ll give you sixty dollars, and I’ll give you even more if you bring me some that doesn’t look like it’s been run through a hay bine.”

“OK,” Travis said, surprised at Leonard but more surprised at himself, how tough he’d sounded. He tried not to smile as he thought of telling guys back in Marshall that he’d called Leonard Shuler a cheater to his face and Leonard hadn’t done a damn thing about it but offer more money.

Leonard pulled a roll of bills from his pocket, peeled off three twenties, and handed them to Travis.

“I was figuring you might add a couple of beers, maybe some quaaludes or a joint,” Shank said.

Leonard nodded toward the meadow’s far corner.

“Put them over there in those tall weeds next to my tomatoes. Then come inside if you’ve got a notion to.”

Travis and Shank lifted the plants from the truck bed and laid them where Leonard said. As they approached the door Travis watched where the Plotts had vanished under the trailer. He didn’t lift his eyes until he reached the steps. Inside, it took Travis’s vision a few moments to adjust, because the only light came from a TV screen. Strings of unlit Christmas lights ran across the walls and over door eaves like bad wiring. A dusty couch slouched against the back wall. In the corner Leonard sat in a fake-leather recliner patched with black electrician’s tape. A stereo system filled a cabinet and the music coming from the speakers didn’t have guitars or words. Beside it stood two shoddily built bookshelves teetering with albums and books. What held Travis’s attention lay on a cherrywood gun rack above the couch.

Travis had seen a Model 70 Winchester only in catalogs. The checkering was done by hand, the walnut so polished and smooth it seemed to Travis he looked deep into the wood, almost through the wood, as he might look through a jar filled with sourwood honey. Shank saw him staring at the rifle and grinned.

“That’s nothing like the peashooter you got, is it?” Shank said. “That’s a real rifle, a Winchester Seventy.”

Shank turned to Leonard.

“Let him have a look at that pistol.”

Shank nodded at a small table next to Leonard’s chair. Behind the lamp Travis saw the tip of a barrel.

“Let him hold that sweetheart in his hand,” Shank said.

“I don’t think so,” Leonard said.

“Come on, Leonard. Just let him hold it. We’re not talking about shooting.”

Leonard looked put out with them both. He lifted the pistol from the table and emptied bullets from the cylinder into his palm, then handed it to Shank.

Shank held the pistol a few moments and passed it to Travis. Travis knew the gun was composed of springs and screws and sheet metal, but it felt more solid than that, as if smithed from a single piece of case-hardened steel. The white grips had a rich blueing to them that looked, like the Winchester’s stock, almost liquid. The Colt of the company’s name was etched on the receiver.

“It’s a forty-five,” Shank said. “There’s no better pistol a man can buy, is there Leonard?”

“Show-and-tell is over for today,” Leonard said, and held his hand out for the pistol. He took the weapon and placed it back behind the lamp. Travis stepped closer to the gun rack, his eyes not on the Winchester but what lay beneath it, a long-handled piece of metal with a dinner-plate-sized disk on one end.

“What’s that thing?” Travis asked.

“A metal detector,” Leonard said.

“You looking for buried treasure?”

“No,” Leonard said. “A guy wanted some dope and came up a few bucks short. It was collateral.”

“What do you do with it?”

“He used it to hunt Civil War relics.”

Travis looked more closely at the machine. He thought it might be fun to try, kind of like fishing in the ground instead of water.

“You use it much?”

“I’ve found some dimes and quarters on the riverbank.”

Leonard sat back down in the recliner. He nodded at the couch. “You can stand there like fence posts if you like, but if not that couch ought to hold both of you.”

A woman came from the back room and stood in the foyer between the living room and kitchen. She wore cut-off jeans and a halter top, her legs and arms thin but cantaloupe-sized bulges beneath the halter. Her hair was blond but Travis could see the dark roots. She was sunburned and splotches of pink underskin made her look wormy and mangy. Like some stray dog around a garbage dump, Travis thought. Except for her face. Hard-looking, as if the sun had dried up any softness there once was, but pretty—high cheekbones and full lips, dark-brown eyes. If she wasn’t all scabbed up she’d be near beautiful, Travis figured.

“How about getting Shank and his buddy here a couple of beers, Dena,” Leonard said.

“Get them your ownself,” the woman said. She took a Coke from the refrigerator and disappeared again into the back room.

Leonard shook his head but said nothing as he got up. He brought back two cans of Budweiser and a sandwich bag filled with pot and rolling papers. He handed the beers to Travis and Shank and sat down in the chair. Travis was thirsty and drank quickly as he watched Leonard carefully shake pot out of the baggie and onto the paper. Leonard licked the paper and twisted both ends.

“Here,” he said, and handed the marijuana to Shank.

Shank lit the joint, the orange tip brightening as he inhaled. Shank offered the joint back but Leonard declined.

“All these times I’ve been out here I never seen you mellow out and take a toke,” Shank said. “Why is that?”

“I’m not a very mellow guy.” Leonard nodded at Travis. “Looks like your buddy isn’t either.”

“He’s just scared his daddy would find out.”

“That ain’t so,” Travis said. “I just like a beer buzz better.”

He lifted the beer to his lips and drank until the can was empty, then squeezed the can’s middle. The cool metal popped and creaked as it folded inward.

“I’d like me another one.”

“Quite the drinker, aren’t you,” Leonard said. “Just make sure you don’t overdo it. I don’t want you passed out and pissing my couch.”

Travis stood and for a moment felt off plumb, maybe because he’d drunk the beer so fast. When the world steadied he got the beer from the refrigerator and sat back down. He looked at the TV, some kind of Western, but without the sound he couldn’t tell what was happening. He drank the second beer quick as the first.

Shank had his eyes closed.

“Man, I’m feeling so good,” Shank said. “If we had us some real music on that stereo things would be perfect.”

“Real music,” Leonard said, and smiled, but Travis knew he was only smiling to himself.

Travis studied the man who sat in the recliner, trying to figure out what it was that made Leonard Shuler a man you didn’t want to mess with. Leonard looked soft, Travis thought, pale and soft like bread dough. Just because a man had a couple of bear dogs and a hotshot pistol didn’t make him such a badass. He thought about his own daddy and Carlton Toomey, big men who didn’t need to talk loud because they could clear out a room with just a hard look. Travis wondered if anyone would ever call him a badass and wished again that he didn’t take after his mother, so thin-boned.

“So what is this shit you’re listening to, Leonard?” Shank asked.

“It’s called Appalachian Spring. It’s by Copland.”

“Never heard of them,” Shank said.

Leonard looked amused.

“Are you sure? They used to be the warm-up act for Lynyrd Skynyrd.”

“Well, it still sucks,” Shank said.

“That’s probably because you fail to empathize with his view of the region,” Leonard said.

“Empa what?” Shank said.

“Empathize,” Leonard said.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Shank said. “All I know is I’d rather tie a bunch of cats together by their tails and hear them squall.”

Travis knew Leonard was putting down not just Shank but him also, talking over him like he was stupid. It made Travis think of his teachers at the high school, teachers who used sentences with big words against him when he gave them trouble, trying to tangle him up in a laurel slick of language. Figuring he hadn’t read nothing but what they made him read, never used a dictionary to look up a word he didn’t know.

Travis got up and made his way to the refrigerator, damned if he was going to ask permission. He pulled the metal tab off the beer but didn’t go back to the couch. He went down the hallway to find the bathroom.

He almost had to walk slantways because of the makeshift shelves lining the narrow hallway. They were tall as Travis and each shelf sagged under the weight of books of various sizes and shapes, more books than Travis had seen anywhere outside a library. There was a bookshelf in the bathroom as well. He read the titles as he pissed, all unfamiliar to him. But some looked interesting. When he stepped back into the hallway, he saw the bedroom door was open. The woman sat up in the bed reading a magazine. Travis walked into the room.

The woman laid down the magazine.

“What the hell do you want?”

Travis grinned.

“What you offering?”

Even buzzed on beer he knew it was a stupid thing to say. Ever since he’d got to Leonard’s his mouth had been like a faucet he couldn’t shut off.

The woman’s brown eyes stared at him like he was nothing more than a sack of manure somebody had dumped on the floor.

“I ain’t offering you anything,” she said. “Even if I was, a little peckerhead like you wouldn’t know what to do with it.”

The woman looked toward the open door.

“Leonard,” she shouted.

Leonard appeared at the doorway.

“It’s past time to get your Cub Scout meeting over,” she said.

Leonard nodded at Travis.

“I believe you boys have overstayed your welcome.”

“I was getting ready to leave anyhow,” Travis said. He turned toward the door and the can slipped from his hand, spilling beer on the bed.

“Nothing but a little peckerhead,” the woman repeated.

In a few moments he and Shank were outside. The last rind of sun embered on Brushy Mountain. Cicadas had started their racket in the trees and lightning bugs rode an invisible current over the grass. Travis tried to catch one, but when he opened his hand it held nothing but air. He tried again and felt a soft tickling in his palm.

“You get more plants, come again,” Leonard said from the steps.

“I was hoping you’d show us some of that fancy shooting of yours,” Shank said.

“Not this evening,” Leonard said.

Travis loosened his fingers. The lightning bug seemed not so much to fly as float out of his hand. In a few moments it was one tiny flicker among many, like a star returned to its constellation.

“Good night,” Leonard said, turning to go back inside the trailer.

“Empathy means you can feel what other people are feeling,” Travis said.

Leonard’s hand was on the door handle but he paused and looked at Travis. He nodded and went inside.

“Boy, you’re in high cotton now,” Shank said as they drove toward Marshall. “Sixty damn dollars. That’ll pay your truck insurance for two months.”

“I figured to give you ten,” Travis said, “for hooking me up with Leonard.”

“No, I got a good buzz. That’s payment enough.”

Travis drifted onto the shoulder and for a moment one tire was on asphalt and the other on dirt and grass. He swerved back onto the road.

“You better let me drive,” Shank said. “I was hoping to stay out of the emergency room tonight.”

“I’m all right,” Travis said, but he slowed down, thinking about what the old man would do if he wrecked or got stopped for drunk driving. Better off if I got killed outright, he figured.

“Are you going to get some more plants?” Shank asked.

“I expect I will.”

“Well, if you do, be careful. Whoever planted it’s not likely to appreciate you thinning their crop out for them.”

Copyright © 2006 by Ron Rash. All rights reserved.

The World Made Straight

- Genres: Fiction, Literary Fiction, Suspense

- paperback: 304 pages

- Publisher: Picador

- ISBN-10: 1250075130

- ISBN-13: 9781250075130