Excerpt

Excerpt

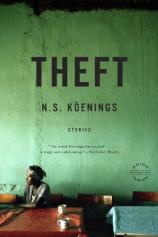

Theft

P e a r l s t o S w i n e

Western Europe, Summer 1980

A weaker person than myself might have been changed by so much rudeness. By what happened in the garden. But I am still the same. I will not frustrate a hungry child or snub a thirsty man. With proper guests, a visit would be smooth. Our home and grounds are gracious. I have not given up. I do still like the sound of silverware on dishes, and a good raspberry jam ferocious in a jar. A bedsheet turned down by the pillow, an ironed towel on a chair. But you know, vraiment on ne sais jamais. Think twice, I say. Be careful. Because once you've given them a washcloth and a bed, nothing can protect you. Not your sweetness, not your natural desire to involve an honored stranger in your life, and not even --- here's the worst --- not even your good taste.

And yet, how pleased I was at first. Before telling Gustave my idea, I went into the tower rooms one after the other and gazed onto the grounds. Just look at those big fields, the pine trees in the distance! See how pale and blue the town, the bathhouses, the spires, so small from our fine heights! And closer in, how promising the urns looked on the patio --- filled with snow just then, but already I could fathom them abubble with petunias. And beyond the berry hedge, the real curiosity: the animals Gustave fashions from the bushes. Now, that's something to look at! A camel and a horse, an egret and a pony. Yes, we have a world unto ourselves. Filling my big eyes with grass, the pines, and sky, I practiced what I'd say when I went up to his office: Gustave, I'd say, in a bright, loud voice so he would have to pay attention, it's time we had some guests.

It isn't that we're lonely or have nothing to do. Gustave has many things to occupy his time. There's that big collection of clay potsherds and celadon, and nice beads made out of glass, which he has gotten through his work --- for we have crossed the world on lecture tours and digs --- and he has other hobbies. A person in Bulgaria, to whom Gustave pays large sums, mails butterflies and moths. Gustave frames the specimens and hangs them in the hallway. Those butterflies alone could give an afternoon of pleasure! And, as I've already mentioned, there's that very special zoo: the topiary, as Gustave likes to say.

Every other Tuesday in the summer, people come from town to see, though Gustave worries for the beasts. He fears the children will strew carbonated drinks and ice creams in the flowers. But I called l'hôtel de ville especially, to say that they could come. To date, which you would notice on your own if you were to come out on a tour, and as I've already said, Gustave has a horse, an egret, a camel, and a pony. He's begun a tortoise, too, but it is taking him a little longer to complete, which I for my part think, ha ha, is not a big surprise. And better twice a month when you expect it than at any time they please, I said. So the people come from town, though when they do, Gustave goes upstairs.

I myself am always busy. I could have my hands full, for example, with just the correspondence. Though we've not traveled in some time, I keep in touch with all the people we have met. Why, just three days before the first girl came I wrote another letter to Morocco's Minister of Culture, and I told him, as I always do, that I will never let myself forget how kind he was to us, how nice the ride on the Corniche so very long ago, and how much I did appreciate that very sweet mint tea. He'll reply in his own time, I'm sure. And of course, I cook, I pickle things. I read.

I make preserves for us when the berries come in summer. I like to tease Gustave and say that both of us excel at keeping things just so: You dig and prune, I say. I pickle and conserve. We're both proud of how we label things --- Gustave says precision with a label separates the shoddy from the great. In fact he had just typed up a card for a new butterfly and was pinning the blue thing onto a heavy cotton sheet when I went to his office. I said, to see if he would soften up, that those gauzy little wings were the color of our winter sky, but he did not answer me. He said something about labels, and I had to interrupt. That may well be, I said, about the labels, but what we need here is guests. Some visitors, I said. All those foreigners we've met, they've been so generous with us. It's our turn now to push back into the world the kindness we've received.

Gustave was thinking of the bushes, if you please. "I don't want strangers tramping on the grounds," he said. He was mumbling, as usual, pin between his lips. I told him I would never ask into our home a person or any pair of persons who would be capable of tramping. Tramping. We ought to send some invitations for the summer, when everything is best, I said. We have so much to give.

"Do what you like, Celeste," he said, and because he couldn't open wide for fear the pin would fall, his voice came out a blur. I did do what I liked, of course, although I wish sometimes, looking back, that Gustave had put his foot down. Afterwards, he said it could have been predicted. That mixing comes about through hard, unpleasant business: if you find a Chinese plate with a plain old East Coast pot, you'll know there was a war. Never some sweet intercourse, or friendliness, or trade, as I thought might be likely. Gustave, whose place it is to know, insisted: war, each and every time. And as to pots, he even said, "It's fortunate for us their owners are long dead and we won't see the carnage for ourselves." Well, that may be fine reasoning or poor when it comes to beads and bones, though I reserve my judgment. What I do know is that he doesn't understand the world of living beings like I do, that we need company and gentle conversation. Gustave even said this morning, "At least they didn't hurt the bushes." The bushes!

So I sent out my invitations, one to my old friend Sylvie, who now lives in New York, U.S.A., and the other one to Liège, which although it is not very far from here you might think another country. I wrote to La Maison des Jeunes Femmes Abandonnées, which has a well-known program for the girls they like to help. From New York, Sylvie wrote to say it would be wonderful if Petra came to see us. The House in Liège was also very gracious. The nuns would send us an unmarried girl who had fallen into difficulty but would by then be on the mend, and to whom our kindness was surely going to do a proper world of good. I had brightly colored dreams in which the two became great friends. It was exciting to envision --- one girl come from Liège, another from America, not a thing in common but their girlhood and the grounds.

We've been all over Europe and the best places in North Africa, but never to New York. I think it would be charming. I know some feel the U.S.A. is poor in taste, from the Rodeos to that big Statue and le foot Américain. Yvette said so herself when I told her where Petra would be coming from, and she was wrapping me a nice half kilo of pâté. She said, "Don't buy too much of this, then. Hamburgers, that's all they like to eat." Well, I took my regular half kilo and paid her no attention. I'm sure I don't agree. Where would we be now without Americans, I always like to say.

When I told Yvette the girl Thérèse would be coming from the House, she threw back her big head and gave a hard snort through her nose. "She'll steal the sheets from under you," she said. I thanked her very nicely and snuck a sample of salami while she was counting out the change. Her view of human nature is nothing to be proud of, but I can get along with people of all kinds. Don't I send my flowers to the abbey when the beds come into bloom? I was sure Thérèse would be well mannered, and that Sylvie's girl would bring me some nice gifts from big and busy, interesting New York.

Petra came three days before Thérèse. I had just washed the breakfast dishes, and was having a verveine by the window in the library upstairs, where Gustave has shelved my novels. Our place was blooming with the springtime! We had sparrows shaking in the trees, and the baby bees, though it hadn't quite got warm, were spying on the ivy. I was wearing blue. Gustave was standing by the window with a cup of Chinese tea, looking out at nothing as he sometimes does, and, nodding at the glass, he called out to me. "It must be Sylvie's girl," he said. I went to stand beside him, and as I pulled the curtain to the side I caught a whiff of his tobacco. I straightened up my slip beneath my skirt and set my toes right fast in the bottom of my shoes. I held my head high. Here we are, I thought, the hosts. And what a couple we still make. I stood beside my husband, and I looked down at the girl.

She had traveled from the station in a taxi. Her driver was a fat man, panting with the case he'd just extracted from the trunk of the Maria. He'd left the engine running. I could see the steam rise from the cab. And I could see the girl. Wild hair, thick and dark. A velvet purse was dangling from one long bony arm, and she was fumbling with her money. I thought Gustave must be wrong, that it had to be the other one, the unfortunate from Liège come a few days early. When she bent to gather up the coins she'd scattered in the stones, her spine showed through her dress. It can't be, I told him. That's got to be Thérèse. That cotton dress had seen far better days, and her white socks were bunched up at the ankles from a pair of buckled shoes. They must have got the days confused, I said, moving closer to my husband. Below us in the drive, the girl was nodding-bobbing at the driver as though he were a head of state, a king.

"No, don't you see?" he said. "She looks just like her father." All I could make out was that her dark-haired head was large and the rest of her was thin. The fat man raised an empty hand up to his temple and moved it in an arc out from his brow as if he were a gentleman tipping a good hat. The girl was easily amused, I saw. She giggled as he popped back into the cab.

I watched the taxi barrel down the drive, skidding on the gravel. Strange, I thought. Cars like his take people on fine trips now, and we don't think about it twice. Used to be a Black Maria meant the S.S. were out and coming to take stock. Well, the girl had no idea. As she said later, she feels like an American, doesn't know a thing about it, not Marias, not potato cakes, not hiding in a basement. And she's never heard of chicory.

Anyway she must have felt us looking at her, or perhaps a bird flew by, or there was a rustle in our ivy. Because she lifted up her chin and I saw exactly what she was. My goddaughter, what a sight. Gustave was right, she did look like her father --- an Antwerp face with dusky, caterpillar eyebrows, like something in a cabaret. Though it was clear she was a girl, and it's true she was attractive in a serious sort of way, with a big and heavy head --- a Hannah, or a Ruth, if you can get my meaning. Then I looked hard at her hemline and at those awful crumpled socks, and I caught sight of her knees. She did have stunning calves. That one time Sylvie came to Tunis with her husband, I remember thinking Hermann's shapely legs were wasted on a man.

She didn't have the sense to come knocking on the door. She just stood there, holding to the suitcase with both hands, that old purse drooping to the ground on its sorry knotted string. She stood biting at her lips, frowning at the ivy. A baby! Sylvie said she was sending a grown daughter and instead we got a baby. I thought, It's a good thing Gustave heard the car come in the first place, or she'd have stood there until lunchtime and we'd not have known a thing.

Downstairs, Gustave took her case away. She tried to shake his hand, but instead he put his arm around her shoulders and brought her in himself. I was quite surprised at him, although you will agree Gustave can be disarming when he remembers where he is. Arching her long neck like a farsighted person at a bug that's landed on their chest, Petra looked as if no man had ever put his hands on her before. What a cardigan! I thought. A thing the color of pea soup that slid all over her, and by the time she'd come into the foyer it had fallen off her shoulders and was bunched around her elbows. To convince myself again that this was the delinquent girl instead, I squinted. I opened my eyes wide. Let this not be mine. But it was not to be.

At that moment I was so distracted by her looks I couldn't think what her name was. Gustave --- bless him, he always knows what things are called --- must have sensed what I was thinking. "Petra," he said (to help me, I believe), "this is your godmother, Celeste." When she looked at me and smiled, she looked exactly like her mother and it took my breath away. Here is what was strange: she had her father's lips, full and wide from top to bottom, but quite short side to side, yes, Persianlike, you know, but when she smiled and brought out dimples, I could see old Sylvie laugh. What a combination. Dear God, I thought. Out loud I said, "That settles it. Petra. Goddaughterof- mine." Gustave rolled his eyes, but I think he was amused. I kissed Petra on both cheeks and while I was leaning in she took my hands with hers and held them very tight. She kissed me back with her eyes closed. I smelled milk and eucalyptus on her. She's not a woman yet, I thought, no, she's just like a sick child.

I told Petra I'd have lunch for her quite soon, that she should bathe and change her clothes. She didn't speak, but she turned pink. Sylvie's smile and that dark hair. I never did get used to it. Gustave took her to the tower room, which I thought would be pleasant for her since you can see the chamomile and from the other window on clear days the bathhouses in Spa. I wanted her to understand how nice it is here, and to make sure Sylvie knew it, too.

She spent a very long time upstairs, I thought, and she used a lot of water. When she came down, her hair was even blacker. She'd tied it in a rag and changed into some trousers. I myself don't wear them, but women these days will, and she looked a little better than she first had in that dress. Brown trousers with a periwinkle blouse, and the pea-soup cardigan again. I thought she looked Polish. Or Italian. Petra.

For lunch we had salade frisée and eggs and some nice slices of roast beef I'd got in town from Chez Yvette. I asked Petra if she had ever eaten this before and Petra said that yes, her mother made it here and there, but the lettuce she was used to was not so nice as this. That bath must have done her good because she wasn't shy at lunch. She finished off the salad and asked for more meat twice. She clutched the fork in her right hand and barely used the knife, which I forgave her at the time, because they left when she was three.

Petra's French was not too bad. She didn't have an accent when she spoke, and although later I kept hoping that the girl would make mistakes, she didn't. But she thought hard about what words to choose, and sometimes she'd wait with her mouth open in an "o" until the right thing came to her. Son séjour améliorera peut-?tre son français, her mother'd written, hoping we could get the language streaming through her daughter's blood again. Elle n'a personne avec qui parler. Well, Petra had two people now to speak it with, and I impressed the fact upon her. We'll talk a lot together, you and me, I told her. I have a lot of novels. Petra nodded carefully across her empty plate. She was quiet for a moment. I wondered if she was imagining the two of us together on the terrace, as I was, companionable, sipping our cassis.

As it turned out, she spent very little time with me, even early on. Instead, she worked it up to say that she was very enthusiastic about walking by herself. She would like to see the grounds alone. Like a mental convalescent, I thought then (she did sometimes seem gloomy). "J'marche vite," she said. And I thought of telling her that I, too, in my time, could keep up a fine pace, but she smiled like Sylvie does, and to be truthful I felt warmly towards her, yes I did. I thought, She is a good child.

Gustave, who is not a hearty eater, was already drinking coffee. He said to Petra that if she was going to be looking at the topiary could she please not touch the animals, as he liked to be meticulous with the shaping and the binding of the boughs. I did feel he was harsh with her. He should put up a sign, I sometimes say --- "Do Not Feed the Animals!" --- and see what people think.

After lunch, Petra followed me right into the kitchen and I almost fell over with the shock of it when I turned and saw her with our three plates and silverware stacked up in her arms. The cardigan had slipped right off her back again. "Can I help you?" she asked me. I thought of telling her that it's not done to stroll into strange kitchens dropping dishes into other people's sinks --- that's rude even in Morocco. But I didn't, no, I slapped those words right back down my throat, and said, Not today, dear. You sit down and start behaving like a guest. She was not stupid, no. I think she understood. She handed me the plates and then her mouth closed and she shuffled back without another word.

Gustave left the table, as he does, and while I was rinsing off the plates I heard him say to Petra that he was going to frame a something-polyxena, and how it's also called Cassandra, would she like to see it? She said thank you very much for now, perhaps some other time. When I came out again, Gustave had gone upstairs and she was standing by the window. She said she'd like to take a walk. Enjoy yourself, I said. She did not know how to please, it struck me then, but surely she did want to.

You know I'm always up at five to make the bread. For those first three days I made cramique, with raisins and lump sugar, which I save for special times, and I'd set the table fresh with cloths we got in Egypt. Damascene, they call it. And arrange the fruit jars in the center of the table: gooseberry, blackberry, and, my favorite, a clever marmalade I do with winter oranges from Spain. Then I'd pull the heavy curtains up so I could feel the light change. I love this place the best at dawn, when the sky gets keen with that strange blue that comes between the sunset and the night. I had an aunt who used to say that blue meant it was l'heure des loups, when wolves can see but people can't. Though my eyes are pretty sharp, I tell you.

I'd put coffee on the stove and sit down by the window in the dining room to wait. I myself like mon petit café at ten o'clock, with a novel on the patio, but coffee in the morning is a habit Gustave picked up in his travels, before he married me. And Petra liked her coffee, too, I found out on the first day. At first she got up early. And she did dress for breakfast, not like Americans we see in films who wear their bed clothes to the table. But she drank more coffee than Gustave ever does, three cups one after the other, like grenadine in August. From then on, I made sure there was enough for Gustave, too, when he came down at eight.

After breakfast Petra would go off by herself. She didn't think to ask me if I'd like to sit with her, or if I had a book that she could read. I suppose she didn't show much interest in us. But it seemed all right at first. She's just a child, I'd think, and she was raised abroad.

We'd have a lunch at noon, and then a nap for Petra and Gustave while I sorted out the dishes and planned the next day's meals. Chicons and veal on the first day, then quiche Lorraine, with mushrooms from the woods, which we still had for dinner on the third because I made enough to last. Reibekuchen with salami for our dinner on the second (because there was no need, I thought, for Petra to imagine we were fancy all the time), and on the third for lunch a filet de sole with asparagus besides, and for dessert a crème brûlée.

Just the day before, the nuns had called from Liège to say that everything was set for the poor girl and they would put her on the train at seven in the morning. We could expect her here by lunchtime if she caught the omnibus, and earlier if the train was an express. But we ate the sole and les asperges, the three of us, alone. Gustave very wisely said, "She'll get here when she gets here," and there was nothing to be done. Petra said that now, yes, she would like to see those butterflies if Gustave was going to be free. He raised his eyebrows very high, as though he couldn't see her well, and shut his mouth quite tightly, as though thinking. Then he held his elbow out so she would have something to hold, and they went up the stairs with Petra asking if he'd strolled the mountains with a net and caught them all himself. "No," he said, with quite a throaty voice, I thought. "My beauties come to me." She laughed. I stayed right there at the table with my crème brûlée. I do like a dessert.

Later I went out to the patio and sat down with my novel. A story by Françoise Sagan, it was, in which a young Parisian girl fools her student-suitor with his worldly sailor uncle. It's silly, but I even wondered, not seriously, you know, if Petra had a boy at home and now was upstairs eyeing Gustave and the butterflies as this girl in my book was doing with the uncle while the wife stitched napkins in the garden. It was a lovely afternoon with lemon-colored sunlight --- cool enough to wear a wrap, and the geraniums in their pots were brilliant, shivering now and then, just giving up new flowers. I wondered where Thérèse was.

As it turned out, it was Petra who came across her on her walk, which she took after Gustave had shown her all his frames. She went inside without my seeing her and called me from the dining room, through the open window. Once the three of us were in the house and I was settling my mind around the look of the new girl, Petra told me how it was. She'd gone into the woods, she said, and she was heading for the abbey when she saw a stranger on the path, struggling with a suitcase. "I asked where she was going, and, imagine, she was coming here!" Petra looked --- although I didn't like to think it --- like a dog that's found an old shoe in the grass, very happy, and her color was quite high. Strands of her thick hair were loose and springing like fresh parsley. That French was really flowing in her veins again, and hotly too, to look at her.

"N'est-ce pas merveilleux? At first I thought she must be wrong." I don't know what is marvelous in meeting with a plump girl who is sweating through the woods and finding out that she is going where you've come from when you know that she's expected, but I will give Petra credit for at least being surprised that we would knowingly invite a girl like that to stay in our fine home, despite how it all ended. I'll just tell you now that Thérèse was not at all as I'd imagined.

What did I expect, you ask? Someone thinner, first of all. Worn by care, and shy, not well fed, but pure. Before she came I could already see myself scooping squares of butter from the loaf and slipping them into her soup while she looked the other way. Someone pale, whom I could fatten up. I'd thought she might be gaunt. The sisters wrote, back when I arranged the thing, that by the time she came to us she would have had the child and a good home be found for it already. They were particularly pleased about our place, the head sister had written, because "it will soothe Thérèse to recover in the country." The letter had made much about the fact that just beyond our woods there is an abbey. "She will be close to God," they said. Oh, it's silly, perhaps. We ourselves don't go to church, because Gustave won't allow it. But I expected someone just a little saintly, someone who'd been wronged. Someone I could look over and think, as Gustave does when he contemplates his potsherds and the dullest of the moths, Her kind will inherit the earth.

But there was not a saintly thing about her. Just as Petra did not look like her mother, Thérèse was nothing like I'd thought. She was like an abbot, not a saint, the kind of abbot in a Brueghel painting you can almost hear. A loud one, yelling about pigs, and belching in between. There was something oily, too, an unctuous glow about her nose and lips, a thickness to her. Her hair was dark and just as greasy, rather thin, and falling on her face so she was always peering through a fringe. Her eyes were very narrow, and blue like morning glories, which I do admit surprised me. She had heavy forearms and thick hands, with two rings on her big fingers, plastic, the kind with a false jewel glued on you find in bubbles at the newsstand.

Welcome to Spa, Thérèse, I said, anyhow. Her dress was the color of blood oranges, very raw and sunny. It was far too small for her. She was quite a fat girl, really, soft and loosened in the middle, and it was clear she didn't know at all how to make herself look smaller. Her waist was done up very tightly with a yellow plastic belt that was meant to match her dress. I thought, She looks like an actress in the vaudeville. But I remembered she had had a baby, and maybe that's why she was fat, and perhaps that dress would fit her in another month or so. That's right, I told myself she was too poor to buy herself loose clothes. I even felt that when she knew me better I could reach out to her forehead with my hand and rearrange her hair, tuck it back behind her ears so I could see her better.

But then she spoke --- with what a voice, I tell you, low and even like a man's. "Madame," she said. Nothing shy about her blue ones, sharp, they were, like mine. Petra was in the kitchen making tea, which she had never done before. Well, I sat down with Thérèse at the table and asked about her trip. We expected you at noon, I said. Honestly I didn't mean to chide her, but she did take it that way.

"Forgive me, I had things to do," she said. She began to pluck the brambles from the sleeves of her bright dress. I watched her press them to the table in a line, and I thought that even with her crumpled socks Petra looked more saintly. This girl wore high heels --- dancer shoes that matched the belt, with ankle straps that bit into her feet. I thought, No wonder she was sweating in the woods.

Conversationally, I asked, "What things?" So she could see I'd be her friend, I scooted closer to her, leaning forward in my chair. I smiled, I did. "Things." She put her elbows on the table and started pulling at her cuffs. She crossed her legs and swung one heeled foot back and forth at me. What she said next to me with that low voice I still can't quite believe. "Private things, if you have to know." The look she gave me would have got a rise out of a man. I know I sat up tall. With those narrow eyes still on me, she scooped the brambles up into a pile, then brushed them all at once to scatter on the floor. Then she propped her chin up with her fist and gave me a thick smile. I knew then that she had tricked the sisters, and tricked me. She hadn't come here to recover, and she hadn't come to be near God. I didn't like to think what private things she meant, but I had some good ideas.

Petra came in with a tall pot of verveine and three good coffee cups, looking quite excited. I was too unsettled at the time to tell her that's not how it's done --- there's a cupboard full of lovely china meant for tea in the next room. Thérèse dropped five cubes of sugar in her cup and stirred her tea quite noisily, I thought. Petra sat across from me and beamed. Petra was behaving as though this girl were a queen --- doing all she could to please her, at least that's how it looked to me, right at the beginning. It wasn't really a warm day, but I felt peculiar, let me say.

Thérèse said in her deep voice, "The pony's nice, though. Who would take the time to make a pony out of bushes?" They had passed the topiary, of course, on their way up to the house. I was about to answer her, thinking, at least she's found something considerate to say, but I could see that she was saying it to Petra. Petra nodded smoothly --- as though she'd lived with us for years --- and said proudly, "That's Gustave who did it." She gave me that smile of hers and poured me out some tea. I was going to say something about the china. But I couldn't. You understand me, don't you? It would have been silly then to talk about the cups.

Here's what it was like in our house after the bawdy girl arrived: loud, dangerous, and strange. Gustave liked her! While I was telling myself all the time to feel good things about Petra, who couldn't help where she'd been raised or looking so much like her father, Gustave, when he paid attention, behaved as though Thérèse was a something-polyxena. It must have come from that digging in the earth he does, which I've always thought unhealthful. "For buried treasures, ma jolie Celestine," he's often said to me, "you must put your hands in muck." Well, that may be fine for broken pots, that muck. But it's another thing for girls.

Her lipstick! I would say to him. She came down to meals with her mouth the kind of red that looks like accidents there is no pleasure in recalling, red like a balloon. Her paint would mark my things: the forks she used, my crystal glasses, the napkins that we bought in Egypt. And no matter what we're meant to think of napkins, that they're for making stains on you'd rather not see on your clothes, I know whoever thinks so hasn't washed white Damascene by hand. Once I asked her, not to make a fuss but I was curious, Do the sisters allow you girls to put on makeup out at the Maison? My voice was very cool, as though it weren't important. "Am I at the sisters' now, madame?" She looked right back at me and took such a bite of mashed potatoes I heard her teeth scrape on the spoon.

All Gustave could say, weakly, absentminded, as though I were asking about curtains, was "She's pretty, Celestine." He'd look up from the clay bits he had set out on his desk and put his cold hand on mine. "We've had nothing bright in this house for so long!" I thought then that I do have three different shades of pink I do put on my lips if I am going into town. But when Thérèse put her shiny mouth on everything, it hit me that maybe Gustave's never noticed. Not for a long time. She's rude, I'd say. "No, no," he'd say, as though he'd spent any time with her to judge. "She's spirited, that's all. C'est la joie de vivre." Joy, is it? I would think.

At dinner that first night the girl asked me straight out how much I'd bought my blouse for --- the ruffled silk one I had made in Liège, you've seen it, light blue with long sleeves and those sweet golden clasps. Then she said, Why spend more than two, three hundred francs on something you were just going to take off. The way she looked at Petra then, it made me wonder what she thought one did exactly after taking off a blouse. And Petra! Petra's sunken little cheeks looked so flushed to me just then, I nearly asked if my goddaughter, too, was taking up the face paint.

Next Thérèse turned to Gustave and asked how much he thought our old house could be worth. "Expensive keeping this house up," she ventured, talking with her mouth full. "You could make a great hotel here, really quelque chose, and bring some German tourists." Germans! Thankfully, Gustave didn't hear her right. He just looked at her over his glass of vin de table and let out a little "hmm." He looked at her so much you'd think he'd never seen a girl.

At breakfast she dropped jam across the tablecloth because she'd talk and shake her knife before the berries could get safely from the pot onto her toast. When she saw the coffee cups, she said, "Oh, moi j'bois du chocolat." I brought her cocoa in a cup and, looking through her oily hair, she said, "Celeste, you don't have any bowls?" It made me shiver, that, to hear her use my name .

To top it off, she sang. I'd hear her from downstairs sometimes, bellowing up there. Not nice songs, either. Not "Les Cloches de la Vallée" or something like "La Vie en Rose," that I could sing along to, but ditties she must have learned from sailors, or the father of that child the sisters said she'd had and given up. And there'd be Petra laughing up there, too. My goddaughter, chortling, learning the refrains. That was the very worst of it, I think, that she had Petra eating from her hand.

The last time I'd seen Petra she was no bigger than a bread loaf and she was swaddled up in white. It was me who held her while the priest splashed water on that powdered baby head. I'll witness this new child come waking to the world, I said to Hermann and Sylvie. I'll care for her if anything should happen. I shudder now to think it. Long life to Hermann and to Sylvie, I say each time I pour out a cassis, if I catch myself in time: ? la bonne votre, I say. L'chaim! Is that not what the Jews say? Though I did try to be nice to her, I did. I offered to go with her to the topiary several times. She'd only glimpsed the pony after all, at least that's what I thought, and it does take some time to see how fine, how delicate, those beasts are. I myself like on hot days to take shade under the camel. We could walk among the beasts, I said. But each time I asked Petra, she said, "Not yet, not yet," measuring her answer like salt into a spoon. "I want to wait until I can't bear not to go." Whatever that could mean. I was hurt, that's the truth. But I kept trying with her.

I never let her do the dishes, and I insisted that she leave the tablecloth for me. I like to brush the crumbs together first, then shake the cloth outside --- for birds, you see --- and Petra wouldn't have, I know, thought of such a thing. But I did everything I could. I made sure that she had coffee, food enough to eat. I filled the cold box with roast beef for her and two kinds of Edam. I did more than my part, and it's a shame that Petra couldn't see it.

I barely saw them after breakfast. They would disappear upstairs, and I'd hear nothing from them until noon. Sometimes I'd see them walking through the kitchen, coming from outside, when I didn't know they'd gone. No, I'd spend whole mornings in the house, thinking they were in the library, finding things to read, or napping, only to discover they'd been playing in the woods. How did they get out? Unsettling, it was. Sometimes it made me wonder if I knew where I myself had been.

Well, I was feeling strange already, but it's the topiary did it, that first Friday morning. That's when I knew for certain the whole thing was a mistake. I had come in from the patio and picked up Gustave's demitasse and saucer from the table. The day was green, we had a dim and chalky sky, and it was defi- nitely damp. I was standing at the sink, as I often do, looking out the window just above the taps. From the kitchen window I can see a nice expanse of chamomile, which, when it's pale outside, all looks very soft. When the wind blows it's got quite a smell, like a steeping cup of tea. Just beyond it I can see as far as Gustave's bushes.

The sweetest one is certainly the pony. Gustave read up on breeds before he did it, and this little bush is now a perfect Shetland, feasting on the grass. From the kitchen I could see it, and the egret, too, although it's smaller, and that big old bucking horse. Gustave is proud of that one, which took seven years to build. And, like the Shetland, it's a special breed. A Lipizzaner, if you want to know, with flaring hoofs and hairy ankles, up on its rear legs.

Well, at first I thought I'd seen a bird. We do get gulls out here, though we're far out from the sea. A flash of white, it was. But then it passed again and I thought it was a flag. But could that be? I put down the cup I had been washing --- a fluted one, gold-rimmed, which I used for Petra's coffee --- and took some steps outside and got out my wolf eyes.

The white thing was no kind of bird or flag at all, but Thérèse's very blouse afloat above her head. She was running back and forth between the Shetland and the horse, skipping now and then --- just like a horse would, I dare say. Of course she didn't have the blouse on anymore, and she was bouncing, you know what I mean. I could hear her yelling, too, or laughing.

There's no cover among flowers. But a standing person is much more quickly seen than one who matches the horizon. When I got a little farther down the hill, I crouched down. I did then as soldiers do. I got out of my shoes and tucked my feet under my skirt. I rolled my sleeves back and got down on my elbows. It was a hot day, remember, despite how gray it was, and I felt very damp. I could feel some nettles on my legs --- that itch! --- but a person will put up with pain if there's something dreadful happening. Tell me, I thought, this time out loud --- as though the flowers could have helped me --- that she's out there alone.

In vain, it was. Next I saw Petra shooting out from underneath the horse, laughing just as loud. Her parsley hair was loose, and she waved her purple scarf around to match Thérèse's flag. Petra got down on all fours and pranced over to the pony and then she huddled underneath it. She had kept her blouse on, that was good, but it hurt to see her chuckling with that girl while I was by myself. I thought, They are playing hide-and-seek.

Thérèse was not a handsome girl, not really, and she had just had, supposedly, a child. So she had little business taking off her skirt, but that's exactly what she did. She was standing right in front of Petra and she let the brown thing drop and she stepped out of it, still hollering. Something like, "Oh! Cruel cavaliers!" or "Come here, cavaliers!" In her yellow panties! Even from where I was lying I could see how her reddened thighs, their plump insides, were wobbly just like my preserves are when they've come out clear and right.

Then she started leaping. On the down, she'd crouch and dig her fists into the grass and pull some up in clumps. On the up, she'd raise her hands into the air and let the grass clumps go, so the blades would scatter wildly. Up. Down. Up. Down. With my good eyesight I could see that loose grass sticking on her, although from where I was and with the greenish light the blades looked black, like tiny eels, pasted to her limbs. Petra turned her head away and then I saw her arms come up around the pony, from below, like the strap that holds a saddle to a horse. She was pretending to be scared, but she must still have been laughing.

Thérèse sang another song. I couldn't make all of it out, but I did hear Petra's name, "Petra, ma belle. Petra, ma jolie." My hair started to prickle then, from heat, and I felt water pooling in my eyes. I wanted them to stop, but --- it's terrible to say, and here's what it can come to when you bring the wrong girls home --- Thérèse made me feel shy. Laughter can really harm a person, don't you think? On my own land I was too frightened to go down there myself and order them to stop. I got up on my knees again. I took one look back near the kitchen and the last thing that I saw before I pulled myself onto the tiles and locked the door behind me was Thérèse, in a pair of yellow panties, raising up a leg in a very loose and ribald way as if to mount the pony's back. Petra had been ruined.

I knew I couldn't tell Gustave. He might have fainted, or had a heart attack, and I would have had to ask that big girl for help. And while, God forgive me, it would have done poetic justice if she caused her own host's death through all that foolishness of hers, of course I couldn't tell him. And perhaps they hadn't done the bushes any damage. But I was damaged, I can tell you that. The nettles were the least of it.

That night Gustave was in good spirits with a call that had come through for him from Egypt. It must have rung while I was shoeless in the field. I'm usually the one to fetch the phone, and I enjoy it, especially when it's a foreign scholar. North Africans, they are, professors. They're always so polite it makes my toes curl and my ears feel very damp. It made me even angrier with that big girl, that she'd made me miss my call.

A year ago it was a man calling from Khartoum, asking if Gustave would be their guest and give a talk, as they'd found something new out there. Of course we couldn't go, and Gustave later said they hadn't any money, something about the Sudanese professors all being kicked out of their schools and how the man I'd talked to was a fraud. But still, that professor'd been so nice to me I felt I should remind him that I was someone's wife. In any case this call from Alexandria had Gustave very pleased, and he opened up a bottle of Sancerre, which I do like very much. Of course Petra drank it like she drinks her coffee, as if it were water, but Thérèse drank hers very slowly. She sat circling the mouth of her wide wineglass with a finger, which as you know will coax a humming sound. I thought, That's the way to make a crystal glass explode, but I couldn't bring myself to say so.

I can't shake the feeling, either, that that night after the scene among the bushes there was something new with us, sitting at the table. The two of them looked different. Petra didn't talk. She hadn't worn her cardigan. She'd put on a black blouse without sleeves that had a pointed collar and buttoned at the neck. Perhaps it was my headache, but it seemed to me her arms glowed, as though she'd rubbed them down with vinegar or lard. She was drinking like a fountain.

I made a point of asking her what she'd done all day, to see what she would say. She looked up very coyly and couldn't keep my gaze. Her eyelashes were so very wild and long, they looked like those tarantulas Gustave has a picture of. Gets those lashes from her father, I thought, or maybe that Liège girl had lent her some mascara. Petra couldn't keep her eyes on me, and she only nodded at Gustave, who was explaining how the two of us might take a trip in winter. "To Alexandria," he said, "where the world's best books once were." Petra said, "A trip is nice," and Thérèse gave out a smothered little laugh, as though she had in mind some journeys of her own.

But all in all, she was quiet, too. Now and then she made a show of listening to Gustave's every word, blinking her blue eyes at him like the wings on a still butterfly that's sucking at a flower. I chewed a bit of anchovy from the salad for a long and salty time, and then I took another. Though thinking about Alexandria did make me feel better. Not so dirty, and not so --- oh, I hate to say it --- old.

I asked Thérèse if she would do the dishes, please, and told them all that I was going to bed. She must have been accustomed at the sisters' to doing work around the place, because she said she didn't mind. She got up from the table and she strode into the kitchen before I had folded up my napkin. Perhaps she was relieved. Perhaps it was too much to ask her to behave like a person who belonged. I peeked into the kitchen then before going up the stairs, and it was true, Thérèse knew how to care for our domestic things: she was very careful with the plates, put spoons with spoons and knives with knives, she did not break a glass. My head hurt and once I got to bed I wished Gustave would hurry up and lie beside me. One likes a man's warmth, now and then.

I know they say if you are on the trail of evil, evil you will find. And when you've brought it home yourself, in some ways it's your fault. But the worst was yet to come. I've said already how I like to get up early, how the house is mine then, in the hour of the wolves. Well, I woke up extra early for the whole of that next week. I couldn't sleep past four.

The first morning I thought I should stay in bed a little longer and try to pull some warmth out of Gustave, who when he's sleeping deeply doesn't mind it if I curl myself around him. But my eyes were open wide, and you know it's wearing to be conscious by a man who's sleeping like the dead. So I made myself get up.

The sky was black, not blueing at the edges, and once up I felt good. I took to walking through the whole of our big house, corridor by corridor, up each and every hallway, as though I were on patrol. Our bedroom is au premier, which Petra found amusing. For her it was on "the second," and downstairs was "the first." Why the ground, which is most of all itself, ought to have no number she could never understand. Anyway, I'd walk first up to the second floor, where we've closed up the rooms. I'd take a candle with me and try not to think too hard about all the gathering dust. It was drafty, too, and even in my housecoat I was chilled. But the cold will do you good, I always say, cold will keep you sharp.

It made me feel just like a girl, wandering in that house with nothing on my feet, awake while everybody slept. I'd walk all the way past the central staircase and to the far one that goes up into the tower, and then down again, in stone. They were in the tower --- that's where I had put them, one room across the landing from the other, Petra's looking out to Spa over the pines, and Thérèse's, come to think of it, with a nice view of the chamomile and of my husband's zoo. I'd put gardenias in their rooms the day each of them came, and I'd given them replacement flowers to take up on the Thursday just before that hideous, hideous show. I liked to tell myself that I could smell the petals in the stairwell --- a cool smell, that, so white.

The first few times I made my rounds, the girls' doors were both closed. Shut very tight against me, that's what it felt like. I'd move to each in turn, and listen. I hoped that they were sleeping well, honestly I did. I wished each of them good dreams. The best ones come at dawn, they say, and that's what I think, too. One morning I tried to think of Petra as a baby, how she'd looked when I held her up to that old Brussels priest so he'd toss some water at her. When we walked out onto the Sablon she didn't make a sound, not even when we passed the antiques vendors, and you know how startling, how pushy, they can be.

Like I said, I'd make the rounds, and then go on as usual, as though I hadn't slept a little less than a person really should. I'd make the bread and coffee, set the jams out in a row, and put out four fresh napkins. I'd read in the dining room until Gustave had come for coffee and to tell me what he was tackling that day. Once Thérèse arrived, Petra stopped coming down so early. No, the girls came down so late I left them to it. It was as if we had no guests at all, just a presence, and even --- when Thérèse took to washing up the breakfast dishes, too --- as though we had a maid. But I tried to be forgiving. I thought, Well, all right.

With all of my patrolling, I'd get tired in the afternoons. And the truth is you can't keep watch with your eyes closed. I'd go out with my book onto the patio and in spite of all my fears I always fell asleep and when I woke up it was six. I'd wake up very cold and need to get a cardigan upstairs, then race into the kitchen to start cooking for the evening.

It's because I fell asleep that those girls got so free. If they'd told me they had dreams of going into town, I would have taken them, I would. I would have pointed out the extra bicycles we keep in the garage beside Gustave's MG. And I would have remembered how the sisters had advised me not to let Thérèse wander alone. That she needed supervision. But I think now that several times they looked as though they'd been doing things in secret --- something hot about their hair, and the way they'd come down from the tower, sometimes holding hands.

When I discovered I was missing money, I can't say I was surprised. It must have been Thérèse. Because although Petra had a slight look of the cabaret about her, she was not born in the gutter. And if Petra knew of it, or if she had a hand, well, she would not have done it all alone. Sylvie may have gotten married to Hermann, but that does not mean she was dishonest. It was after dinner that I found my wallet short. After I'd made them all a quiche, with which I'd served a plate of carrot soup and sweet creamed radish greens. I'd had my purse out in the kitchen, because I thought I'd make a list of things to buy and slip it in the outer pocket so I'd know right where to find it. I didn't plan to count my money out right there, but something made me do it. And I have to tell you, though it pains me, that one thousand francs were gone. Gustave was in his study, and I couldn't go to him. He'd have told me to be more careful with my things, that precaution and precision are welded at the hip. As though my jams aren't labeled nicely with a date on every pot. As though I deserved it.

Well, it was one thing going to the tower rooms while the girls were fast asleep, but quite another to go up when I thought I'd find them wide awake. I waited. I'd go to them in the dawn. Maybe Thérèse would be dreaming thickly and so dead to our world that I could look through the girl's luggage and find my thousand francs.

It didn't turn out that way, in the end. I never got that far. The last day was a Monday, I remember, because as I was walking down the hallway in the dark I made a note to bring the mower out to straighten up the lawn. When the townsfolk come on Tuesdays, I've often got some tartelettes or bigger pies that I make the day before and leave out for the children, and I also thought that I could choose the apricots and pit a bucketful by noon.

I was just coming to the landing on the tower steps when I heard it the first time, and I blew the candle out. I set it down just near the door, and I noticed very sharply how the air was warm above the wick and the smoke around my ankles made the rest of me feel cold. It was a kind of shuffling, what I heard, the kind of noises thieves must make at night. It wasn't even four yet, so I thought, what could she be doing? I thought for sure it must be Thérèse, since she'd already stolen from my purse. It stood to reason she'd be up this time of night, doing things of which I could be afraid. But it wasn't. Or it wasn't only her.

Petra's door was open. I could tell because there was a moon. The light was shining through her window, and it would have glowed right through my dressing gown and shown me if I hadn't slipped myself very nimbly flat against the wall. At first I thought maybe Petra had a fever. She was making little sounds like children do when they're asleep and in the clutches of a cold. I thought I'd go to her and ask if she was well. I think I would have liked that: when you haven't any children of your own you think sometimes how nice it would be to help them when they're sick. I could bring a cool cloth for her forehead, sing a little song. But it was the moon that stopped me, how it glinted off a gold thing on the dresser before I looked closely at the bed. I'd got quite near now, had my fingers on the lintel. Like I said, I see quite well at night.

The gold thing was Thérèse's vinyl purse, unzipped at the mouth. And next to it --- I saw, because I squinted both my eyes --- was a pile of Petra's things, her Illustrated Guide to Belgium, Liechtenstein and Luxembourg, and a vial of L'Air du Temps. In the corner --- which gave me quite a start --- was Petra's purple case. Right beside it was Thérèse's yellow one, pointing straight out from the wall, like a pair of Gustave's shoes. On the chair there were some clothes, and it was another shock to see that old brown skirt tangled up with Petra's pea-soup cardigan, thrown one over the other. What's the use of making up two rooms if your guests are going to go behind your back and share a single one? I didn't like to think about the two of them so close, their things mixed up like that.

Of course it wasn't just the things that were pressed up together. Petra wasn't by herself. There was a lump beneath the blankets with her. Thérèse was a lot bigger than Petra, so I knew that lump was her. I heard that shuffling again, hands tight on the sheets, a sort of nighttime cooing, which sometimes Gustave makes. I must have made a sound, because they suddenly went still. All my breath went sailing out of me and into that warm room. I was like Lot's wife, I was, rooted to the ground.

I wondered how long they'd been together in one bed --- if on the other days when both the doors were closed I was missing something all along. You can't know what goes on behind a door, not really, even if your sight could pierce the wood. My eyes were smarting in the dark, and it wasn't from the smoke. I looked over at the desk again to where that purse was gleaming, and I thought, That's where my thousand francs are. I wanted to walk right in and past the bed and take my money back, but my feet were stuck like leeches to the skin of the cold floor.

I did try to rally. So what if they know that I'm right here, I thought? They ought to be ashamed. The covers moved then, and that's what set my legs free, but I couldn't go inside. I reached out and shut the door, and then I ran downstairs so fast that I was panting in the kitchen. I went directly to the chambre froide, where we keep all the apricots and berries, and sat down against the door.

What would you have done? You understand I couldn't have the girls here any longer. Not like this, not mashed together in one room making plans against me. I'll tell you what I did. I didn't bake the bread that morning. I pulled out the ends from Sunday and had a cup of tea, which calmed me, made me think of England. They'd make the coffee on their own, I thought. I'd forget about the money if both of them would go.

In the end, Petra did it for me. She came down in that old dress of hers, long arms bare, her hair all wild and loose, and found me in the kitchen. "No coffee?" she asked me. And when I pointed to the Maragogype in the glass jar on the counter, she set to making it herself. I'd been crying, but I'm sure it didn't show. If it had, Petra would at least have kissed me on the cheek, or told me to sit down.

"Listen, marraine," she said, very friendly, as though nothing wrong had happened. In fact more talkative than she had ever been. "We'd like to go to Liège, to spend a few days there, is that all right with you?" She turned the gas on with the lighter, then walked into the dining room. "I thought, you know, that since this is my first summer en Europe, on irait m?me ? Knokke. That's where the beach is, isn't it? Have you ever gone?" Well, I guess that "we" was Petra and Thérèse, though if she'd told me from the start, I could have gotten used to the idea and we would have gone together. I've been to Knokke once or twice. Blue sea, Italian ice in tiny cones, and a pretty little wind. I could have planned it for her if she'd told me. But it was clear she meant Thérèse. I told her she could do exactly as she liked. I didn't tell her that Thérèse was not allowed to go off by herself, or that I'd promised Sylvie I'd take good care of her daughter, make sure she was safe. I walked right past her to the bread box and got myself some jam. Gooseberry.

They must have agreed to act as though I hadn't seen them in the night, as if I didn't know that they had turned into a force. I couldn't bring it up to Petra. Not to Sylvie's little girl. She watched me chewing, and I had to put the bread down. I didn't like her eyes on me. I told her I was going to change my clothes. On the way, I got my courage up. If I couldn't tell my goddaughter exactly what I thought of her, I'd say something to the other girl. That's right, I thought. I'll talk to this Thérèse.

Petra's door was open, and Thérèse was in the room, which I guess she had come to think of as her own, and she was looking in the mirror. Mouth tight and open like a fish, she was putting on her lipstick. Still holding her mouth like that, which made her voice peculiar, she said, "Celeste," and my name sounded strange. With a tip of her big brow, she told me to come in.

I sat down on the bed. I saw her bags were packed, and I felt the wind go out of me again. It's crazy, isn't it? I'd gone up to tell the girl to go, that I'd be calling to the sisters to expect her, but when I saw she'd beaten me to everything, it almost made me sad. I hadn't thought that things would go so fast. You're leaving? I asked her. Today? I looked at my own hands along the crocheted bedspread for a moment, and though I didn't mean it, I was tatting at the blanket like a child. Thérèse put on her belt. She breathed in very hard to make her waist as small as it could be before fastening the buckle. Trussed up like a sausage, she let all the air out that she could, and then said, very softly, which was not her usual tone, "Ah, non. Merde!" I looked to see what she was doing. She was not speaking to me. She was frowning, looking down. My mouth went very dry. It's not pleasant to say, but the fact is that there was a stain on the girl's bodice. A leak, I mean. You know. She reached down to the bureau for a handkerchief, which she pressed against her breast and then tucked tight and rather easily into her brassiere. When she looked into the glass again, more herself, or nearly, Thérèse smiled at me. You'll wonder what I did. I crossed my legs and leaned towards her. Serious. I had something to say. But my throat wouldn't open. When she spoke she sounded sorry. "C'est pas grave," she said. "It doesn't matter." I wasn't sure what didn't matter. She looked down at her chest. I nodded, I suppose. Then she put a hairpin in her mouth and started combing her brown hair. For a girl who cared so much about her looks, I thought, she isn't very lucky. Rather a lot of that thin hair came out into the teeth. She went on, "Petra wants to see the coast." Her hands moved very slowly. "A rest would do me good." She put the comb down, and she blinked. "All of that nice wind."

I was looking at her eyes. Very blue, they were. I looked into the mirror at myself to see if my own were that blue, too. I even wondered if her baby's eyes would turn out that same color. Then of course it came to me that Thérèse would likely never know, because she'd given it away. It didn't bother me just then that she was looking at me, or that we do get winds right here, and as I said, now and then some gulls. But it did make my jaws hurt, that they were leaving me before I could order them to go.

Then she made me jump. "It's not so bad, Celeste," she said, and winked at me. That wink felt like a slap, you know, the way you feel when you've held out a piece of cake to someone, and they keep talking and don't take it, though your hand is plain as day. The plump girl winked at me just like an actress would, as though we had a secret. And that wink helped me pull myself together. I do not balk at hardship. I smoothed the blanket down.

I said, You'll be out before lunch, then, and she looked a bit surprised, and I tell you I was pleased. I didn't feel like unwrapping any meat for them or cracking any eggs. I made myself get up from the bed and I went to see Gustave, who was in the study. He was clacking at the typewriter, and he didn't hear me when I pushed open the door .

The girls are leaving us, I said. And though sometimes I sneak up very close, and quietly sit down on the free arm of his big chair, I couldn't make myself go in. "That's strange," he said. "So sudden." And he kept clacking at the keys. "Both of them?" Clack-clack. Both of them, I said.

I waited in the tower staircase at the bottom, while the girls packed their last things. I made myself very small. I heard Petra going down one flight, but she did not come to me. She slipped across to Gustave's room to say good-bye, and I'll give her this much, she sounded awfully polite. Her French had gotten better. Then she came bouncing down in that pale dress, that cardigan pulled tight around her bony little waist. I asked if she wanted me to call a car for her, but she kissed me on the cheek and said they'd walk their luggage down the hill. "Don't worry about us," she said. "I'll write you." She giggled. "We'll send you a card!"

Did she think I'd gone to all the trouble of inviting her out here for the summer so she could run off to the beach with a cheap girl who'd given up a child? I guess she did. I guess that is exactly what she thought. I was wrong. I'd been wrong from the start. Here is what I thought about while she stood waiting in the hall. She never gave me presents from New York. She'd never smelled like eucalyptus or like milk. She was not well behaved.

Thérèse came down with her yellow case. She was far more able with her suitcase than Petra was with hers, what with those broad arms. Thérèse stopped in front of me and I noticed that her posture was not bad. She looked right into my eyes. She'd put some hairpins in, and they looked very neat. I could look at her whole face. "écoute," she said, "tu vas quand m?me pas leur dire?" She was asking me quite underhandedly not to call the sisters to tell them she was gone. It's a special program, don't you see? One they were just trying, and if Thérèse did any wrong she'd not get help again. And girls like her don't manage without help, do they? She'd also given up on vous, and maybe if she hadn't I'd have made a different answer. "Of course I am," I said. "I will telephone the very moment you are gone. Don't think you'll get far." Thérèse considered me and the import of my words. Then she shook her head and closed her eyes. As if the wayward girl was me! I opened the front door for them myself, and then I stepped aside.

At first while they were walking I imagined calling up the sisters and telling them precisely what I thought about their large, abandoned girl. How I'd done my best for her, but when someone hasn't any manners nothing's going to suit them. And how she'd damaged me. At the same time, and I can't tell you why it is, I also felt the way a person does after they have made a lovely meal and the guests are getting up to go. That sad, sweet peeling into darkness that makes you think you'll do it all again. And how you wish that they would stay, just a little longer.

It was another green, dull day, a whitish sky like thin, gray milk, and the girls stood out quite sharply. When they reached the very end of our long driveway Petra turned around and waved at me, with that strange smile on her face, which was both Hermann's and Sylvie's. Though just then it didn't look quite like her mother's or her father's, and it wasn't Persian, either. Thérèse only turned her head over her shoulder, and maybe she smiled at me, too. The bells rang from the abbey for the morning mass. In the stillness, from the upper road, which is rather far away, I could hear a car. I didn't wave at them, exactly, but I did curl my fingers in my pocket. Well, I suppose I made a fist.

Petra waited, then she shrugged, Thérèse leaned on her arm a moment, and the two of them walked off. From far away, you know, they looked like two ordinary girls. Nothing special. Certainly not horrible, not from a distance like that, when they were growing smaller and I could hear their footsteps echo in the gravel, their cases dragging on the ground. You wouldn't have known at all as I did that Thérèse had had a child, or that it had been taken off to someone else, or that she was the kind of girl who'd drop her skirt so easy. She was having a hard time with her dancing shoes and swollen feet, but I supposed once they found the blacktop she would be just fine. I couldn't help but think: After all, they did have extra money.

When I went back inside, Gustave was sitting at the table with his demitasse and a magazine on Pharaohs. "They're gone, then," he said. And I said yes they were. Then he said the coffee didn't taste quite right, and I can't help it but I told him Petra made it, and that made me feel better. I went into the kitchen for the apricots. Tomorrow's Tuesday, I told him. There's a topiary tour. He groaned. "I wish you'd stop all that, Celeste. It's like throwing pearls to swine."

I stuck my head out and I looked at my own husband. Pearls to swine. There he was, the famous archaeologist, telling me about giving pearls to swine. I left him at the table and went in to make the pies. I must have gotten very busy with them, and that's why I never made the call. In fact it was already afternoon when I remembered. And the number for the sisters was all the way upstairs. And then, well, I put the pies in and washed up, and once it came to me that I'd forgotten, well, it seemed a little late. I did tell Gustave I had called, so he'd be relieved that I am not a person to be fooled with. I even told him, though I am not the sort of woman who will trifle with the truth, that the nuns were informing the police and would make them bring her back to Liège. He nodded at me once, then went back up the stairs.

Already I could smell the apricots get warm and soften in the oven. I went into the hall and pulled the cloths out for the tables. I could iron them and get them fresh before the pies were done. I set up the tables in the field, not too far from Gustave's beasts. Later on I'd clean the two rooms in the tower, make them fresh again.

The pies came out quite well. I arranged them in a circle on the kitchen table and covered them with cloth. Then I went out onto the patio with a glass of bitters and some ice and a novel I had longed to read. The sun came out at last. The petunias were as sturdy and as bright as I had hoped they'd be when I'd watched the urns in winter. I could smell the chamomile and very slightly, too, my baking. I opened up the book and before I started reading I thought how pleasant it was going to be when lots of children came to look at Gustave's zoo. If they would finish off the pies, and thank me, and promise to come back.

Excerpted from Theft © Copyright 2012 by N.S. Köenings. Reprinted with permission by Back Bay. All rights reserved.

Theft

- paperback: 264 pages

- Publisher: Back Bay Books

- ISBN-10: 0316001864

- ISBN-13: 9780316001861