Excerpt

Excerpt

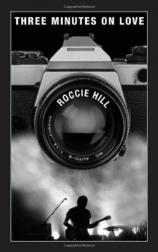

Three Minutes on Love

We lived in the desert when I was a kid, in a climate without water where the plants looked like weapons and the sun-scarred colors of the soil and rocks were like none other on earth. Our neighborhoods had been drawn in graph-paper boxes across the parched Pinto Basin, with even, hot asphalt streets of air-conditioned stores and houses. Inside our town’s shopping mall the developer had built a plaster waterfall and painted it turquoise, and all day long hundreds of gallons of water were pumped over it. This waterfall was where we went as children if we got lost; it was where we met our friends in high school. ‘Meet you at the waterfall,’ my mother would say to me, but it was not until I left the desert that I understood the irony. This was our community: fueled by someone else’s water and someone else’s electric power. Even then we were kids of excess, although we never knew it. I grew up on a street of identical houses with deep-green lawns and dark, moist forest soil. My father had planted borders of bright pansies and geraniums, red and purple and pink. He set the automatic sprinklers to water three times a day to keep them alive, laboring over those frail flowers. Most families on our block had kidney-shaped swimming pools the dark turquoise color of sweet Hawaiian cocktails, and I remember that my father wanted a garden of ferns surrounding ours. Year after year he would plant new ones, drench them, and watch them die. Our town was a shield against the sun for spillover GI families from the California coast, with an air-conditioned house for each one, where only hot rocks and rattlers should have been. Each year new people came, building new schools and cutting more lush green neighborhoods across the empty, dry horizon. People with real estate dreams dug huge trenches into hundreds of miles of land too dry to farm, and into these trenches they sank great pipes to bring the water from faraway snowy rivers to our homes. And this is how I grew up, playing in the heat among those stacks of enormous, sun-warmed concrete pipes that were waiting to be sunk into the cracked desert ground to bring more water to us. I used to dance to radio songs across rows of them, holding a transistor to my ear in the heat and skipping across those huge concrete hulls to "Cinnamon Cinder", a song I always called "Cinnamon Sinner" and whose words I still have memorized. And I remember the first day the water came through those huge pipes. After years of planning and digging, early one fall morning as I sat in my seventh grade classroom, our teacher suddenly stopped talking. I could hear it, or feel it, not a sound but a heavy vibration in my inner ear as though the earth was about to crack open. The water gates lifted high and brought the Sierra-fed rivers into the pipes to our desert, to irrigate the future. My dad was a teacher. He taught math to soldiers' kids out there in the heat where the Air Force kept their secrets. He hated that he wasn't part of it; he had never designed a plane or a landing strip or thought up a formula for a bomb, and although he never got invited to their parties or included in their theories, he stayed to teach their kids algebra. In the hot evenings after school he would sit by our swimming pool drinking whisky and telling me and my mother about the principles of logic and the politics of defense. Sometimes he would drink half the bottle on his own, other times he would leave it and walk along the sloped concrete edge of the pool, and his shadow would be bouncing like a marionette's across the blue glow of the water. Often, my mother put him to bed, and I could hear him moaning down the hall to their room about the importance of logic. He was the first man I knew who told me his job would save the world, and because he was my father, I loved him and believed him for many years. I had no brothers or sisters, so my mother took me everywhere with her. We would go in the car to the movies or out for long drives in the heat, and she would talk about the neighborhoods, when they were built, what ghosts had come since, and what men had slept with others’ wives. She knew everything. She was like a witch taken out of her own lands, and when she told me she could mind-read, I believed her. She read constantly: novels by American expatriates, political books about workers’ rights and the destruction of McCarthy, and obscure religious books about Rosicrucians or voodoo or the lost secrets of the Vatican. She was obsessed with moral harm and secret truths. She had grown up in the Hollywood Hills before the roads were paved, and as she drove through the desert she would tell me her cluster of morality tales about the movie people during Prohibition and how the Hollywood she knew could protect you if you could stay away from alcohol, although in her beauty years she herself had preferred to drink. Her favorite tale was how she, the bootlegger's pretty daughter, had become a movie socialite while playing drunken chess with Harold Lloyd at his crazy parties. She told me that our job was to seek out our one, true soulmate, and once she confessed to me that my father was not her true love. Her soulmate, she said, had been a poet from Hollywood High, a boy who hitchhiked to Arizona, where he walked with a burro for several years until he disappeared forever down a canyon. This was so outlandish that even as a ten-year old child I did not believe it, although I was eaten by guilt for being disloyal. My mother had left the coast with my father because he promised a decent, sober life, and that is what she had for as long as I knew her. She spent a lot of her time waiting in the heat and the bright light, watching the landscape for a movement that no one but she would see. She taught me to gamble while we picnicked on the dry and dormant ground, to play draw poker and blackjack, and when I got clever at those she taught me to play mumbly-peg. It was a game she had learned from clients of her bootlegger father on the beach at Zuma: a dangerous game with a knife that you played to test your skill and your courage. It was not a game for children, but she always expected more of me. The object of this game was to bounce the knife blade from your body to the ground, where your hand lay flat, fingers splayed. The space between your fingers was the target, and my mother used to say this was more a game of geometry than bravery. She had a special knife with a narrow, long blade which cut easily into the brittle, desert, and she was good with knives and never once let me hurt myself. After mumbly-peg we moved on to games like bridge and chess, which she said also took more intelligence than guts. Once she took me out on a drive, early in the morning when you could smell the heat coming hard across the valley. The sunlight turned the creosote branches dark in the early day and the white light behind cut crisp and simple black lines across the land. My mother said, "Look at that. The first pen and ink drawing. Everything you see now will be less." We parked by an old train track and waited and watched. She said, "The desert is never boring. It changes every day. I came here in 1948 with your father, and I would have died from boredom in a city by now. If you can't drink you can't live in the city." We squatted by prickly bushes next to the rusty track, and she pointed out some wildflower growing in the hard, dry dirt. She said, "Rosie, look at that. You'll never see a color so red. How do you get color like that out here? But a change in the weather can kill it. Anything can kill it." And she was right. Even the water we piped to our neighborhoods could kill it. Those desert flowers soon disappeared, replaced by the petunias and pansies. Without my mother I never would have seen the last of the real desert. We sat on a plastic tarpaulin that we had found in our garage, now so hot that it burned the backs of our legs and my mother made us move to sit on the scorched desert floor, because she said the heat of the earth was good and the heat of plastic could make you sick. She pulled warm lettuce and cheese sandwiches from a paper bag, and we ate in the dirt, watching the far, flat horizon. “Do you know,” she said, “there are creatures sleeping under us? Tiny worms you can’t see, and when the rains begin they come to life across this whole valley, thousands and thousands of them crawling for daylight.” I put my hand on the hard, hot ground, not even afraid but hoping I would see one of them. She watched me for a few moments and then touched my shoulder. “Rosie,” she said, “I want to tell you something. Do you see my ears? Do you see I have no ear lobes? My ears are connected, just like yours.” I was eight years old and could not yet distinguish between truth and entertainment. “Well,” she said, “this is because we are descended from an ancient race of aliens who came to this planet thousands of years ago.” “How did they get here?” I asked. “They came in spaceships that they buried in India. This is how you tell our people, by our ear lobes. Whenever you see someone whose ears are connected like ours, you will know they are one of us.” My father didn't understand her stories, and so he was never part of them. But there was still some picture in her mind of a family, and she was afraid of not being good at it. Years later on the way home from a Saturday car trip she said, "Please tell your father you had a good time with me today." I would have anyway. The others were the enemy. Cecilia was her name, a saint's name, the goddess of music. That was the first day I understood that she needed me, the first time I knew I would need to take care of her. I guess I was about eleven. When I was fifteen my mother put the first anti-war poster in our front window. The poster said "Another Mother for Peace", and my father hated it. "You'll have to take that down," he said. "I teach their kids. You can't think like that here. I'll get fired." "I'm tired of eating my dinner while our boys get killed on television," she said. Eventually she took the poster down, but began secretly to organize meetings against the war in the Lutheran Church hall. People from up north would come to help her; young guys with lots of hair would drive in from San Francisco to speak to her groups. My mother, who by then was wearing bead necklaces and strange Egyptian symbols for earrings, would give them dinner and find them places to stay. Because we lived in an Air Force town, the important anti-war people from the cities kept an eye on her, and when they needed someone to feed deserters on their way to Canada, it was my mother they asked. She helped them secretly for years, giving the kids food and clean clothes, sometimes a few dollars, and they began calling her Saint Cecilia. As long as the Vietnam War was fought, she had that secret nickname. The first boy I slept with was one my mother disdained. He was Thomas J. Thomas, the son of a colonel at the base. Tom Thomas had virtually no hair, was a member of the Junior ROTC, the Eagle Scouts, and the Varsity football team. He was a simple kid from a family with simple desires, and he could not conjugate a verb to save his life, something which my mother never let me forget. But he brought me freedom through raging hormones he could scarcely control during daylight hours, and I can remember so clearly lying with him on warm, clean rocks in the purple desert afternoons. It ended in 1967. Tom Thomas and I were walking across a patch of lawn at our school, which was known as the “Senior Grass” and on which only kids of our year could sit. The humor of it had escaped me until that day, when we found a group of younger kids sitting in a circle and holding hands on our grass. They might have been of a different time, clothed in leather fringe and scarves, with so much hair among them. They were kids I'd seen one by one in the school corridors, isolated and strange, and all of a sudden they were sitting together before us, holding hands and doing secret things I knew nothing about. Tom Thomas told me they were dangerous; my mother thought they were beautiful and exciting. Tom dropped my hand and walked to the edge of their circle, standing squarely on the grass. "You ain't all seniors now, are you?" he asked. He wore his football jacket and walked with the loping, swelled presence of a boy happily destined for shopping malls. He should have commanded respect among them, but he didn’t. One of the boys said, "No man, but we're making a movie about what it's like to be seniors." Indeed, another boy had a camera, and turned it on me and Tom. "Come on, Rosie," the camera boy said, "smile for me, baby." "I think that's enough," said Tom in a hollow voice that reminded me of his father. "How do you know my name?" I asked. "Hey, everybody knows your name - you're Saint Cecilia's daughter," he said. Tom Thomas scowled and stepped forward toward the circle. "Go on now," he said to them, and reached for the camera boy's equipment, "or I'll have to get someone." But they laughed and began to sing the Donovan song "Catch the Wind", that sweet ghost tune, in the warm red backglow of the late desert sky. One girl waved a smoky stalk of incense through the still air, and the smell of sandalwood rose around us. I whispered to her, “You really need to go now. Please go.” But they just kept singing. Tom moved forward and lifted one of the boys to his feet. “That’s enough,” he said. He shoved him hard, away from the lawn onto the paved walkway. He grabbed them, one after another, shifting their bodies like sandbags from that important line on the grass, and their music fell to the empty air while they struggled against him. Tom was bigger and braver, and although he was alone, he had been trained to win. I edged back toward the clean, grey wall of the math building, suddenly unsure which side I was on. It took Tom only a few minutes to shuffle them away, leaving the lawn empty in the quickly falling violet desert dusk. By the time he had finished his job, I understood that I needed to leave the Pinto Basin and the people who had begun as my family. *** In the fall of 1968 I went to San Francisco to art school. I left the desert and the painted rocks and the heat, and went to the cool bay to learn how to take photographs. This was a year after the summer of love, and by the time I arrived it had all changed. Venereal disease and heroin were the issues, and any promises of peace and a new society were just disintegrating. The streets in the Haight-Ashbury were filthy; half the shops were closed and used only for sleeping and dealing. My first pictures were shaky ones of street rags on Haight Street, taken on an old Olympus Trip my father had given me. All I knew how to do was point and shoot, but I loved it, and I always had the Trip with me. I'd take half a dozen rolls and only come up with one good shot, but I tried everything. At that age every single thing I saw could have been art, and figuring out what made the one perfect shot obsessed me. Those first months I would go down to the Haight at dawn on the weekends, before the morning sounds began, while the damp and mist clung to the crumbling, Victorian neighborhood. The druggies would be asleep by five am, and I would have the quiet streets to myself, shooting roll after roll of a secret garden of garbage discarded from the wild night before. Rather than take pictures of the children I saw crouching in doorways, the easy shots, I stood on the gutter corners where I found rags, old Indian cotton, discarded and damp and greased over by sewer sludge and cars passing by. Shooting people was the easy way to record those days; everyone was doing it, but I wanted to get a picture of the people from their rags in the street. I was only eighteen then, and I believed that the harder I made the job the truer the art would be. I shot thousands of pictures of the dirt of the Haight, my garbage garden, and hardly any pictures of human beings. In Golden Gate Park I met people who would sit in circles pretending to be ancient Indians, except they would smoke dope and talk of Lenin and the CIA and the war. For hours we sat in the wide Sharon Meadow with music around us and the mist moving in from the cold bay at Ocean Beach. We talked of music as though we had invented it and all of us were certain we would one day be heroes of something. Sometimes a girl would do an odd floating dance around us; sometimes the Krishnas came chanting to us; always the smell of sandalwood clung to our clothes. When the days finished we called ourselves a family though we might never see one another again. Most of us had left our own families, but we kept seeing their ghosts in everyone we met. One Saturday I sat next to a Hungarian refugee named Peter who was older than the rest, although his unabashed excitement at being in America made him seem like a teenager. He had short black hair that receded far off his broad forehead, and a prominent straight nose, sunburned from those early autumn days in the park. He told me he had just escaped from immigration jail in New York and was now the editor of a new music magazine called The Bay Scene. "Because a scene is cool," he said in a heavy accent I could scarcely understand, "and Bay people are cool." He grinned broadly and talked about Trotsky and the agrarian revolution, and he said, "You know, Rose, I think it is easy to make money in this city. There is moral money and immoral money, but in general, being poor is no fun.” He was the only person I knew then who cared about money, and because of this I thought he was unconventional and honest. I told him I knew a boy at college who had gathered up all the mediocre assignments from the pottery workshops and sold them to Woolworth's. With that money he bought marijuana to sell, and with the money from that he had gone to live in Tahiti. "There you are," he said, “the new capitalism.” He leaned back on the grass, stretching his long legs out before him. I could see even then that he was extraordinarily tall, and not quite at ease because of it. He wore a very old navy sports jacket that was missing its buttons, and as he lay beside me, he grabbed nervously at the old button threads and then suddenly stopped himself doing it. He had round black eyes, always a little frightened and quite beautiful. "There are lives for us," he said, "if only we had the money. I am only in this for the money and the women." I laughed when he said that; he spoke too loudly and somehow the words came out as a fantasy, like a piece of America he was trying on. Everything about him was dark, his hair and eyes and obscure cynical economics, until he talked about America. "Would you like to work for me?" he asked. "I need a photographer. I am useless at taking pictures." "What would I have to do?" I had never been offered a real job before, although I had sat in the park for weeks pretending that I was a published photographer. "Come with me to concerts and take pictures of the bands. So easy. And free concerts for you." "Does it pay?" I asked, and he laughed out loud. "Sweetie-pops! This is America. You must never do anything for free. I will pay you five bucks a picture printed." "I'm at school most days," I said. "My people only work at night. This is a night business." "I suppose I could borrow a good camera from school." "Look, do you want this job or not? I am trying to do you a favor. You need to be more aggressive. You will never be successful unless you are pushy." The next time I met Peter, we had coffee at Tosca’s in North Beach where we sat in a smoky room on an old, fraying couch and put our cups beside us on a low table. Part of the room was given over to a piano, and customers would now and then play tunes, mainly jazz music that belonged to the past. Each group of people seemed to know the others and guys moved from couch to couch, straddling the arms and smoking and talking. Peter nodded at most of them, and when we sat down he said, "These are the losers of the city." "Why?" I asked. "Poets. They don't do anything. Most of them might as well pay rent here. There's no money to be made in here. The revolution will come from those of us who control this capitalist economy, not from these loser poets," and he pronounced that word "poots". Across the room, a guy was sitting alone at a table in the corner. A chessboard was set up in front of him, all the pieces in starting position, and he sat waiting, watching it and the door, and straining his neck at the people coming in from the street. "Look at that one," he said. "He plays chess in here every day. And when he's not playing chess he's waiting for chess. You know, some people are the get-aheads, and some people are the fodder. You can always tell right away. I don't know where that guy gets his money from. What about you?" "I get my money from my father, but he says he's running out." He smiled at me. "I didn't mean that. Are you a get-ahead?" "Of course," I said, but I knew that wasn’t true. All I ever wanted was to take good pictures and have a family, and I knew that a real get-ahead had to want more. Peter sat next to me, with his arm across the back of the couch and his fingers on my shoulder. He said, "The music business will save us." He wore a tweed jacket and a red, silk scarf and threw his head back when he spoke. He drank his coffee all at once in a gulp like the French at a sidewalk café, and said, "We will make the art of the revolution through rock and roll. I am only in this for the art.” As he leaned back, I could smell Old Spice across his clothing. “Before we start our discussion, I want to be clear about something,” he said. He coughed nervously, and folded his hands in his lap across his thick waist. His nails were bitten beyond the quick, and he lifted his fist to his mouth suddenly. “This is a business relationship, Rose. We can never have more than that, no matter how much we may be attracted to each other.” He was so timid, his eyes black and scared like a young boy trying hard to be an old-fashioned gentleman. I smiled gently. "All right, I understand." He stood up quickly. "I'll just go get us more coffee." When he returned his hands were shaking slightly. He was holding two tiny cups of expresso on saucers, and the delicate rhythm of his nerves caused the cups to shudder like wind chimes. "Would you like me to take those?" I asked. "Please don’t be offended,” he said, watching the cups and not me. “I don’t really know many people here. Why do I alienate new friends so quickly?" "Peter, please sit down. It’s okay. I’m not offended." He nodded and stepped forward, and he looked down at me, leaning to place the cups on the tabletop. He smiled broadly and helplessly, and as he did the cups tumbled from their saucers, cracking across the table, the coffee splashing over me and the couch. Conversations around the room stopped; a quick silence focused on Peter, who stood motionless, his face flushing and sweating in the smoky, hot room. "Don’t worry," I said, and took a napkin to clean it up. He didn’t speak, but stood shaking before me like a Market Street crazy, the broad, helpless grin still quivering on his lips. He watched me clean the table and pile the empty crockery at one end, and finally, he said, "I think we had better leave." "Peter, nobody cares if you drop a few dishes. This is North Beach. The losers of the city, remember?" "I guess I'm a loser, too." "Sit with me." I reached for his hand. "Dropping cups doesn't make you a loser." "In my family it does. In Budapest." "Well this is North Beach. It doesn’t matter here. Sit down and tell me about these pictures you want me to take." He hired me for that first paying gig and, being honest, it is still the best picture I have ever taken. We went to a cheap neon bar in the Haight to cover Robert Clay, an old piano player who had come to the city with a new, young band. He was one of the real blues people, and he was in San Francisco to showcase his new band and to get a recording contract. He had been on the road for so long, smoking and drinking and shooting heroin, and trying to make some money for that gold limousine. I thought he was ancient, but I guess he was about fifty years old. The bar was called the Skyway Lounge, and the words were painted in pink and black swirling lettering on the big plate glass window. Inside, the room smelled of spilled beer; the smoke was tobacco and pot mixed together. It was a small bar, not a music club, but a paying gig anyway, and I stood like a gawky kid beside the door, juggling my camera bag out of my way to grab my purse, until Peter pushed through and gave our names to the bouncer who checked his list and let us in immediately. For a kid from the desert, this was a ticket to ride; I had become a member of the holy music union. They seated us at a table in the front and brought us a bottle of scotch. Peter believed in the new journalism so he didn't take notes - he said he experienced the story and re-created it afterwards. He sat at the little wobbly table and started drinking out of a thick, short glass that had been put in front of him; when someone brought him some pot, he started smoking as well. He looked around the room, bobbing his head to the jukebox music, smiling like a child and waiting for the show. "I'm going to look for a spot to shoot from," I said. He nodded at me and leaned over to speak into my ear. "Make sure you’re in place. When Robert gets playing you will have to be ready. He is the best living blues piano player. Of course, most of the others are dead. Go on, go do your work." The band was playing, so I went wandering the room for angles and dramatic shadows, but there wasn't enough light to take a picture. I didn't know that this would always be the case, that light was the secret to taking someone's picture and that light was a demon I would chase my whole life. I was trying so hard to be professional, but I hadn't brought the right film for concert photography, and had loaded my only camera with film that wouldn't soak what little light there was. In the end I sat defeated on the grimy floor in front of the stage and held my camera and listened to the set while photographers from better papers slid into place beside me and cracked their shutters. Lots of people had come for this old guy; the news had spread across the city that a real musician was going to play our town. He played gently without jumping or kicking the piano stool back, without moving much at all. He scarcely opened his eyes and his tunes were easy and soft; those simple, deep under-notes that ground into the room, all over the room, those heavy, clear notes that hung there just so easy. He wore a shiny suit like from another decade, an old one soiled from weeks on the road; a handkerchief soaked with his sweat was stuffed in his pocket. Everything about him was out of fashion, but he and his band loved what they were doing, and our San Francisco style at once became irrelevant. After, because he wanted a record contract and he knew the riff, he came to sit with Peter and me at our table in the front of the room where everyone could see he was being interviewed. He drank bourbon and smiled and his voice was so old you could hardly hear him through the smoke. He brought his guitar player with him, a young kid from Canada he had picked up in some bar in the east. The two of them laughed and smoked together and talked about women. The old guy said, "Dave, you gotta admit, I gave you what I promised. You ever seen so many women just dying for you?" The guitarist only said, "No, no man," and smiled. "He's a pretty boy, ain't he?" Robert asked, looking at us. "They'll love his pretty picture on our jacket. I was a pretty boy once." He was looking straight at me, and his voice was heavy and drunk. He put his arm across the table and grabbed my hand, taking my fingers from the glass I was holding. "I could do you. Get in that box. Bring you up, baby," he said. "I could do any woman in this room." He coughed after he spoke, and couldn't stop and the sound of thick phlegm rose from his throat. I was too frightened to speak. I was seventeen then, only a few months out of the desert, and I had never even been in a bar before. Now I was sitting with three drunken men I hardly knew, hoping that the old guy would let go of my hand without a struggle. The guitarist looked over at me. I was clutching my camera with my other hand, my fingers trembling around the casing. He saw this, and in a moment of uncomplicated mercy, he put his hand on Robert’s shoulder and said, "But not this one, Robert. She's got to take our picture and make us famous." He leaned back from the table and as he did Robert turned quickly and drunkenly to watch him, letting my hand go free. He wiped the sweat from his face with his fingers and pulled at his nose. He grinned quickly at the young man showing all of his teeth. "Are you telling me this pussy is for you?" And that's when I took the first picture I ever sold, of the two of them in that dying bar in the Haight, and I took it because I was afraid. David, with dark shaggy hair and big green eyes, high and sharp cheekbones, glanced across at this old piano player, looked sideways at him, with this strange, calm smile in the middle of that filthy place, a smile that could have been about God. Just then the old guy was looking at David like he hated him, sitting at that grubby little table staring at him with raw jealousy. I picked up my camera and hid my face behind the lens, holding it still for a moment while the light passed between them, and then I took a picture of those two, musicians who lived in buses and motels together but never once trusted each other. Peter published it the next week in ‘The Bay Scene'. The band had left then for another date, but a few days after, old Robert hanged himself in the San Joaquin Valley, in a motel in Bakersfield. I had the last picture of him ever taken, and it caught all the nationals, television, and the trade magazines. That issue of the ‘Bay Scene' even sold out and became a collectors’ issue. Soon after that, the photo editors at a couple of national magazines called and asked me to do some work, and I never went back to art school. That's how I started out, and that's how I met David. And I loved that picture, the first thing I was ever paid for, because it caught the hardest truth of that business before we realized it ourselves. I’ve taken tens of thousands of photographs over these decades, but I never took a better one than that. You might say I peaked young.

Excerpted from Three Minutes on Love © Copyright 2012 by Roccie Hill. Reprinted with permission by The Permanent Press. All rights reserved.

Three Minutes on Love

- hardcover: 288 pages

- Publisher: The Permanent Press

- ISBN-10: 1579621694

- ISBN-13: 9781579621698