Excerpt

Excerpt

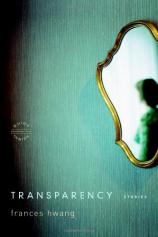

Transparency: Stories

THE OLD GENTLEMAN

As a young girl, Agnes was often embarrassed by her father. Her family lived on the compound of a girls' high school in Taipei where her father worked as principal. On Monday mornings, after the flag had been raised and the national anthem sung, he liked to give speeches to the students assembled in the main courtyard. To get their attention, he stood with silent, aggrieved humility, his arms dangling at his sides, his limp suit already wrinkled from the humid weather, the front pockets stuffed with his reading glasses, a spiral notebook, a pack of cigarettes, and a well-used handkerchief. When he opened his mouth, he did not immediately speak, desiring that slight pause, that moment of breath in which everyone's attention was fixed on him alone. He quoted regularly from Mengzi, but his favorite writer was Cao Xueqin. " 'Girls are made of water and boys are made of mud,' " he declared. Or " 'The pure essence of humanity is concentrated in the female of the species. Males are its mere dregs and off-scourings.' " He clasped his hands behind his back, his eyes widening as he spoke. "Each of you is capable, but you must cultivate within yourself a sense of honesty and shame." He reminded the girls to rinse their mouths out with tea when they said a dirty word. He discussed matters of personal hygiene and reprimanded them for spitting on the streets. Agnes's father had a thick Jiangbei accent, and students often laughed when they heard him speak for the first time.

When Agnes was eleven, her mother was hospitalized after jumping off a two-story building and breaking her hand. The following Monday, her father opened his mouth in front of the student assembly, but no words came out, only a moaning sound. He covered his eyes with a fl uttering hand. Immediately a collection was started among students and faculty, a generous sum of money raised to pay for her mother's hospital bill. A story was posted on the school's newspaper wall in the courtyard in which a student praised Agnes's father for his selfless devotion to "a walking ghost." Older girls came up to Agnes and pressed her hand. "Your poor mother!" they exclaimed in sad tones. They marveled at her father's goodness, assuring her that a kinder man could not be found.

Agnes intentionally flunked her entrance exams the next year so that she would not have to attend her father's school. She ended up going to a lesser school that was a half-hour commute by bus. Sometimes she rode her old bicycle in order to save bus fare.

Her family occupied a three-room house without running water in the school's outer courtyard. Because her mother was sick, a maid came every week to tidy up their rooms and wash their clothes. The school's kitchen was only twenty yards away, and Agnes washed her face in the same cement basin where the vegetables were rinsed. Her father paid the cook a small sum to prepare their meals, which were always delivered to them covered with an overturned plate. At night they used candles during scheduled blackouts, and, with the exception of her mother, who slept on a narrow bed surrounded by mosquito netting, everyone — her father, her brother, and Agnes — slept on tatami floors.

Sometimes when Agnes mentions her early life in Taiwan to her daughters, they look at her in astonishment, as if she had lived by herself on a deserted island. "That was the nineteen fifties, right?" one of them asks. The other says, "You were so poor!"

"It wasn't so bad," Agnes replies. "Everyone lived the same way, so you didn't notice."

What she remembers most from that time was following a boy in her choir whom she had a crush on. When she passed by him on her bicycle and the wind lifted her skirt, she was in no hurry to pull it down again. Some days, she picked up the cigarette butt that he tossed on the street and slipped the bittersweet end between her lips. She kept a diary, and it was a relief to write down her feelings, but she burned the pages a few years later when not even the handwriting seemed to be her own. She did not want a record to exist. No one in the world would know she had suffered. Agnes thinks now of that girl bicycling around the city, obsessed and burdened by love. It isn't surprising that she never once suspected her father of having a secret life of his own.

Her parents moved to the United States after her father's retirement, and for nine years they lived in their own house in Bloomington, Indiana, a few miles from her brother's farm. After her mother's death, Agnes thought her father would be lonely by himself in the suburbs and suggested that he move to Washington, DC, to be closer to her and her daughters. She was a part-time real-estate agent (she made most of her money selling life insurance), and she knew of a government-subsidized apartment building in Chinatown for senior citizens. At Evergreen House, he could socialize with people his age, and when he stepped out of his apartment, he had to walk only a couple of blocks to buy his groceries and a Chinese newspaper.

Her father eagerly agreed to this plan. Six months after her mother died, he moved into Evergreen House and quickly made friends with the other residents, playing mahjong twice a week, and even going to church, though he had never been religious before. For lunch, he usually waited in line at the nearby Washington Urban League Senior Center, where he could get a full hot meal for only a dollar.

At seventy-eight, her father looked much the same as he did in Taiwan when Agnes was growing up. For as long as she could remember, her father had been completely bald except for a sparse patch of hair that clung to the back of his head. By the time he was sixty, this shadowy tuft had disappeared, leaving nothing but shiny brown skin like fine, smooth leather. Her father had always been proud of his baldness. "We're more vigorous," he liked to say, "because of our hormones." He reassured Agnes that he would live to a hundred at least.

Every day, her father dressed impeccably in a suit and tie, the same attire that he wore as a principal, even though there was no longer any need for him to dress formally. "Such a gentleman!" Agnes's friends remarked when they saw him. He gazed at them with tranquillity, though Agnes suspected he knew they were saying flattering things about him. His eyes were good-humored, clear, and benign, the irises circled with a pale ring of blue.

If anything, Agnes thought, her father's looks had improved with age. His hollow cheeks had filled out, and he had taken to wearing a fedora with a red feather stuck in the brim, which gave him a charming and dapper air. Maybe, too, it was because he now wore a set of false teeth, which corrected his overbite.

Every other weekend, he took the Metro from his place in Chinatown to Dunn Loring, where Agnes waited for him in her car. He would smile at Agnes as if he hadn't seen her for a year, or as if their meeting were purely a matter of chance and not something they had arranged by telephone. If her teenage daughters were in the car, he would greet them in English. "Hello! How are you?" he said, beaming.

Her daughters laughed. "Fine! And how are you?" they replied.

"Fine!" he exclaimed.

"Good!" they responded.

"Good!" he repeated.

Agnes supposed the three of them found it amusing, their lack of words, their inability to express anything more subtle or pressing to each other. Her daughters were always delighted to see him. They took him out shopping and invited him to the movies. They were good-natured, happy girls, if spoiled and a little careless. Every summer, they visited their father in Florida, and when they came back, their suitcases were stuffed with gifts — new clothes and pretty things for their hair, stuffed animals and cheap bits of jewelry, which they wore for a week and then grew tired of. Their short attention spans sometimes made Agnes feel sorry for her ex-husband, and she enjoyed this feeling of pity in herself very much.

Excerpted from Transparency © Copyright 2012 by Frances Hwang. Reprinted with permission by Back Bay. All rights reserved.

Transparency: Stories

- paperback: 240 pages

- Publisher: Back Bay Books

- ISBN-10: 0316166936

- ISBN-13: 9780316166935