Excerpt

Excerpt

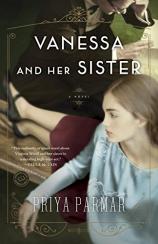

Vanessa and Her Sister

1905–1906

“Your letter was such a blessing. Did I write you a very silly letter?”

(Vanessa Stephen to Margery Snowden, 13 August 1905)

The Party

. l .

Thursday 23 February 1905—46 Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, London (early)

I opened the great sash window onto the morning pink of the square and made a decision.

Yes. Today.

Last Thursday evening, I sat in the corner like a sprouted potato, but this Thursday, I will speak up. I will speak out. Long ago Virginia decreed, in the way that Virginia decrees, that I was the painter and she the writer. “You do not like words, Nessa,” she said. “They are not your creative nest.” Or maybe it was orb? Or oeuf? My sister always describes me in rounded domestic hatching words. And invariably, I believe her. So, not a writer, I have run away from words like a child escaping a darkening wood, leaving my sharp burning sister in sole possession of the enchanted forest. But Virginia should not always be listened to.

A list. Parties always begin with a list. Grocer. Butcher. Cheesemonger. I wish Thoby had some idea of how many are coming tonight. I suggested to Sophie that she make only sandwiches. She said it was barbaric and flatly refused.

Neither Thoby, nor Adrian, nor Virginia would ever think of anything so banal as sandwiches or napkins or tea spoons. Mother or Stella was always there to do that for them. Now I do it. I will speak to Sloper. I am sure we should order more whisky for Thoby and wine for Adrian. And for the guests? Does Mr Bell drink whisky or wine? I can imagine him drinking either. I have no idea what Saxon drinks, but we have cocoa for Lytton, and I am sure that Desmond will drink anything we put in front of him and declare it to be his favourite. Virginia of course will drink nothing.

Later (8.30am)

The morning’s heavy quiet was split in two.

“Nessa!”

Virginia was shrieking downstairs.

“Nessa!”

I ignored it. Thoby was insisting that she eat her breakfast, and Virginia, enjoying his attention, was refusing. Virginia, as a rule, does not eat her breakfast. But last week Dr Savage told us that eating is crucial if we are to avert another disaster. He was dismayed when Thoby told him that Virginia’s room was at the top of the house. He suggested we either relocate her to the ground floor or nail her windows shut.

Scraping chairs. Slamming doors. The escape. Quick cat’s-paw footsteps on the stairs, and Virginia barrelled into my sitting room without knocking and hurled herself into the low blue armchair.

“Ginia. I have asked you to knock in the mornings. Just in the mornings. Any other time, you may behave like the little savage you are and barge in,” I said without looking up.

“Nessa!” she said loudly. “I am being oppressed! Thoby forced oatmeal down my gullet. Libre Virginia!”

The morning was off to a roaring start.

Later (after luncheon)

The interval before the second act. Adrian is down from Cambridge until Monday, and I will not let him out of the house until he unpacks his boxes from Hyde Park Gate. We moved six months ago, and they are still in the hallway. We walk around them like they are furniture. The servants shake their heads at us in disapproval. I can hear Thoby thumping around looking for his field glasses, and Virginia is out visiting Violet Dickinson in Manchester Square. Violet, older, calmer, and robustly good-natured, soothes her. And so we have peace.

A wobbly three-legged day. A current of expectation has rounded through the house since this morning. It races and puffs up the stairs, sifting through the bedrooms in a blur of undefined something, knocking us out of stride. Thursdays have become important, like a bump that defines a nose, or a fence that marks a field. Thoby’s Thursday “at homes” for his friends from Cambridge lend shape to the week. This will be Thoby’s second at home—no idea why he chose Thursdays. He said Mondays were bulky and Wednesdays were flat. I do not mind. George and Gerald always try to frog-march Virginia and me to a gruesome dinner or dance on Thursdays to meet the eligible young men of Belgravia and Kensington. It embarrasses our half-brothers to have such conspicuously unmarried sisters. George is less concerned about Virginia—at twenty-three she can get away with it—but at twenty-six, I am a desperate worry. Strangely, I am not worried. I hate wearing white gloves, and I always find the young men undercooked and sweaty. We were meant to go with George to a dance in Mayfair this evening, but I just sent round a note with my apologies.

I can’t think what to do with the house tonight. Gaslights, which flatter everyone, or the harsh, unreliable new electric lights? Thoby, ever in favour of modernity, wants the electric ones, but they make Virginia and me look washed out and greenish as though we have been eating bad fish. My painting sits on the easel in the corner of the drawing room. Do I pack it away? Do I put away Thoby’s books and Adrian’s exam papers and Virginia’s notes and our decks of cards? Do I pretend that we four siblings do not live here? Stella would have ordered menus. Father would have received guests in his library. Mother would have sent out cards. We four will take our chances and see who turns up. Last week the last guest left at half past two in the morning. At midnight I told Sloper he could go to bed and Thoby’s friends could see themselves out. Sloper looked appalled and ignored me.

Thoby’s at homes have the soft, unpredictable feeling of a hat tossed high in the air. When we moved last autumn, not to a suitable address near the Round Pond in Kensington, nor to a pretty side street in Chelsea, but to the once elegant but now shabby Georgian squares of Bloomsbury, I did not realise what a shocking thing we were doing. Mother and Father’s friends, feeling a sense of responsibility, tried to dissuade us from this bohemian hinterland, and of course George and Gerald objected, but we decided to ignore that. Because there is a sturdy beauty here. These Bloomsbury squares are set in their ways: no longer smart, no longer chic, they remain defiantly graceful. A good bone structure is hard to deny.

And what if people are shocked that we have no curtains and hold mixed at homes and invite guests who don’t know when to leave? Only we live here, and we can do it how we like.

Just us four.

There is a lovely symmetry in four.

Mid-afternoon

I was in my sitting room working on my newest portrait of Virginia when Sloper came to tell me that the wine had been delivered as well as six crates of champagne and eight bottles of whisky. He was concerned, as we have never placed such a large order.

“And what time shall we expect Mr Thoby’s friends?” he asked gravely.

What time indeed.

“Finished!” Adrian called up from the hall. He had unpacked the boxes. “Nessa, I’m finished!”

Adrian still needs to be petted on the head and told well done as Mother always used to do, even though Mother has been gone ten years. Nothing is real for him until someone else approves.

“Wonderful,” I called down to him. Sloper winced and went downstairs. No one shouted in the house when Father was alive.

“Nessa,” Thoby said, strolling into my sitting room. “Do you mind terribly? I think you and Ginia will be the only girls again. Lytton was going to bring his sister, but—”

“Marjorie?” I interrupted.

“Dorothy, I think. I always get the Strachey girls mixed up.”

“Is Dorothy the painter or the don?” I asked, pulling the canvas off the easel and tilting it to the light. It was still not right.

“The painter, but it doesn’t matter because she isn’t coming. We could ask Violet, but she is so patrician. She might make things stuffy.”

“Violet may be aristocratic, but she is not stuffy. You just think that because she is tall and unmarried. She is an eccentric. Stella used to say that Violet wore bloomers when she bicycled.”

Thoby, nonplussed at my mention of bloomers, came to stand beside me to see the painting. “Are the shoulders a bit—”

“Wrong? Yes,” I said briskly.

“But the angle of her head is good,” he said. “It is not that we want to invite girls, you understand. But you two live here, so—” He shrugged as if his comment were self-explanatory.

“Don’t worry. It is much too late to ask Violet. Sophie is in a terrible mood and would never agree to make more sandwiches.”

Late (three in the morning)

They were invited for nine, and Thoby warned us not to expect most of them until after eleven, but a crowd of people arrived early. Lytton Strachey, his younger brother James, both down from Cambridge, Mr Clive Bell, Harry Norton, and Walter Lamb all trooped into the drawing room. They had been to the opera together and left at the first interval.

“Andrea Chenier. Giordano. Disaster,” Lytton said by way of explanation. He handed Sloper his hat and dropped into the basket chair by the window.

“You walked out?” Thoby asked as I poured Lytton his cup of cocoa. Harry Norton and Walter Lamb had drifted to the far end of the room and were looking through the bookshelves.

“Yes,” James said, claiming the other basket chair. “Lytton insisted we leave.”

“We had to leave. It was the most godawful cliché. Milkmaids. Shepherdesses. And there was a huge, puffy paper sheep on stage.” Lytton rolled his eyes. “One must have limits.”

“The sheep was the best thing in it,” Harry said, settling onto the sofa. “It was the singing that was dreadful.”

“Saxon saw it on Friday and told me that the fourth act is wonderful,” Mr Bell said, reaching for his drink. Whisky. I must remember for next week.

“Saxon has more patience than Strachey,” Thoby pointed out.

Nine exactly and Saxon Turner himself walked in. Saxon is never late. “I, ahem, met your brother, ahem, outside,” Saxon said quietly to Thoby. Saxon prefers to speak to one person alone rather than address a room.

Thoby and I exchanged a brief look. George. The dance in Mayfair. I was sure he was annoyed that I had cancelled so late and had come to lecture me. Thoby quickly crossed to the door, hoping to intercept him, but he was not fast enough, and George stepped into the room. Hearty and obvious and unable to conceal his disapproval, George took in the scene. Six men and me in the drawing room at this time of night. We were suddenly playing by the old rules, the Kensington and Belgravia rules. I felt a slim wire of unease pull the room into a tense flat line.

“George,” Thoby said smoothly, “come and meet some friends of mine.” He slowly took George around the room, making formal introductions. Lytton did not stand but offered up his hand like a Russian duchess. George’s face flushed with insult.

“Thoby,” George said in a low, rapid voice, “shouldn’t the ladies have withdrawn?”

“Ladies?” Thoby said looking around. “There is only Nessa. Virginia’s not down yet.”

“You mean there were no other ladies invited to supper?” George said, his voice rising.

“No one was invited to supper,” Lytton added unhelpfully. “We all just piled in afterwards. I am sure more people will pop along later, but I don’t know if any ladies are coming?”

George’s eyes bulged with outrage, and James shifted uncomfortably in his seat, but Lytton giggled and leaned forward to watch as if he were at a racetrack.

“It is hardly Thoby’s fault, Mr Duckworth,” Mr Bell said, boldly stepping into the fray. “We all dropped in unexpectedly, and Miss Stephen has been kind enough to make sure we are looked after. But you are quite right. It is late. We are imposing dreadfully and ought to be going.” I was amazed at how convincing he was.

“Sloper?” Thoby called downstairs. “Would you get Mr Bell a cab?”

“I insist Mr Duckworth take the first cab,” Mr Bell said graciously.

“Yes, absolutely,” Thoby agreed. “It is late, and George, you do have the farthest to go.” He led the way downstairs, and George could do nothing but follow him.

As soon as he left, the mood rose like champagne fizz, and Mr Bell, who had never had any intention of leaving, hurried back to the sofa and the party resumed.

..

Desmond MacCarthy, lean, shambling, and amiable, arrived and collapsed his long frame onto the sofa next to Mr Bell. Thoby questioned him about his newest article. Desmond has a tendency to put off everything, an unfortunate quality in a journalist, and Thoby has been trying to help him meet his deadlines. Last week, Desmond asked Thoby to lock him in his study until he finished his travel piece on Spain. It did not work.

“It was a poor choice of room,” Desmond explained, stretching out his long legs. “There were so many interesting things to read in my study. It was an impossible place to work. Goth, we must find a more boring room.”

..

Eleven. Virginia and Adrian had promised to be down by ten, but of course they weren’t.

I found them in my sitting room, arguing. They knew I would come back to fetch them. Adrian was being pedantic and trying to persuade Virginia to change into evening clothes.

“I do not see why I should wear a corset in my own drawing room,” Virginia said crossly. “You can breathe. Why shouldn’t I?”

“Because you are a lady, Ginia,” Adrian repeated.

“And therefore not entitled to breathe? Since I do not need air, I will swim around the drawing room like a fish. Then what will you do?”

Virginia logic.

I could hear the heavy front door open and close and the sound of voices and laughter drifted up as more people arrived. Anxious to get back downstairs, I quickly re-pinned Virginia’s hair, smoothed her serge skirt, and clasped her jet cameo brooch to her blouse. It does not matter if she changes or not, Virginia is always beautiful.

Adrian stubbornly refused to go down without us and sat fidgeting in the blue armchair. Since he grew to six foot five, he feels awkward and oversized at parties. It cannot be easy to be the youngest and the tallest. Only an inch shorter, Thoby never looks or feels out of place. I pulled Adrian to his feet and tugged at his cuffs and straightened his tie. “Lovely,” I said, hoping to encourage him.

Vanessa and Her Sister

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 384 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 0804176396

- ISBN-13: 9780804176392