Excerpt

Excerpt

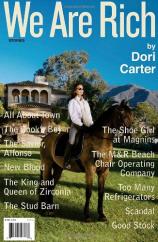

We Are Rich

Dwight D. Eisenhower once said, “We were poor but the glory of it was we never knew it.” Maybe in Abilene, Kansas, he couldn’t figure it out, but in Rancho Esperanza, California, if your family didn’t have money, no one ever let you forget it. I was nine years old when we moved there, and even though the Vietnam War raged nightly on our Magnavox, and a marching-fucking-drugged-out-rampaging youth was upending America (and all but annihilating the Wasp Establishment in the process), Rancho Esperanza remained a town where Old Money and social prominence went hand in glove. Among the rich, and even those of us who weren’t, it was simply understood: pedigree was everything. Not only your pedigree, but your horses’ and your dogs’ as well. My mother, whose parents were humble Danish dairy farmers, took the opposite approach and firmly subscribed to the Scandinavian code of jantelovan --- don’t show off. Though I suspect this was less a family ethos than a realization that we couldn’t anyway, so why bother trying.

Until my father’s death, we lived thirty miles and another worldaway from Rancho Esperanza, in a small, picturesque town founded in the nineteenth century by Danes --- many of whose descendents were devoted to keeping alive the Danish spirit and the colorful heritage of their native land. Not only were the streets named for famous Danes, and the stores and restaurants built in the style of a prosperous Danish hamlet, but gracing our corner park was also a reproduction of the Little Mermaid looking a little perplexed --- the ocean being on the other side of the mountains. It was a village of Danish bakeries and friendly shoppes selling cuckoo clocks, decorative nutcrackers, Royal Copenhagen, Christmas ornaments, and an astonishing assortment of knickknacks that could only be destined for garage sales. Somehow, this was enough to bring in tourists, who ambled down the streets snapping photos of cupolas, windmills, and flower boxes as if they were on a walking tour of Europe. The only visual glitch in this otherwise fastidious tableau were the Mexican workers in bracero straw hats, who came to town from neighboring ranches to sell eggs from the backs of their rusted-out trucks.

Among her fellow Danes, my mother was known for her good looks, her Christmas pickled herring, her meatballs in beer, and her pandekager. Another attractive young widow might have gotten a job in the local smorgasbord, donned a dirndl and lacy white apron, and set her sights on a new husband, but my mother was determined to never again be dependent on a man. Parlaying her limited culinary repertoire, she secured a position as cook to the most prominent family in Rancho Esperanza --- Lincoln and Chicky Crowell. With congenital fortitude she sold or gave away most of our belongings, and we moved over the mountain and into the two-bedroom “gardener’s cottage” on the Crowells’ fifty-two acre estate --- which had been left to Chicky by her parents, furniture and all.

As if to spite the cuddly moniker bestowed in childhood for her downy, flaxen hair, Chicky Crowell grew into a tough old bird whose imperiousness was completely natural, and whose effrontery was imbued with such High Wasp aplomb that she was able to carry it off with a complete and utter lack of pretense. As a child I found her intimidating. I was both anxious for her approval and eager to avoid being in her presence. She ruled her little fief by divine right, and being a lowly squire, I was expected to execute her decrees with alacrity.

“Would-you-please,” she would say, pronouncing each and every word in that punctilious and commanding way she had of addressing inferiors, “load the picnic baskets into the trunk of the car and do be careful you don’t allow-them-to-tip.”

“Would-you-take the suitcases down from the bedroom and place them in-the-front-hall.”

“I need this mailed at the post office as-soon-as-possible.”

I don’t think it ever occurred to Chicky Crowell to care what other people thought, least of all me. But who could blame her? Chicky’s grandfather, Alfred Charles Stokes, had been a good, solid, Anglo-Saxon, Princeton-educated, Midwestern Republican banker who ran for governor of Ohio and --- after he came to Bakersfield, California --- ran a ten-thousand-acre cattle ranch on which oil was discovered. A. C. Stokes then moved his family from the dusty interior to the largest, most desirable ocean-view parcel in Rancho Esperanza. In our little town, Chicky Stokes Crowell was aristocracy as much as any Huntington, Stanford, or Crocker. Chicky’s native sense of entitlement gave her an unquestioning faith in her own actions and opinions. The class distinction she so effortlessly conveyed offended my instinctive sense of justice, never more so than when she referred to me as “the cook’s boy.” In all the years we lived there, I was never sure if she thought it worth her while to remember my name was Peter.

Although I spent a great deal of time in the Crowells’ house --- known as the old Stokes estate --- I never ventured out of the kitchen when the Crowells were in residence. I sat at the white enamel table doing homework or helping my mother grate cheddar cheese for the Welsh rarebit, a favorite of the Crowells’ remarkably unremarkable palate. But when they were on vacation or gone for the day, the kitchen door was swung open and I gained entrée into a world of wealth I’d never imagined. Looking back, I feel sad for that young boy who was so fascinated by the most mundane, even utilitarian possessions --- especially Lincoln’s things: his double-edged razor, the lidded pot of Old Spice shaving soap with its residue of dried, flaking suds. The bone-handled shaving brush made of silver-tipped badger fur hanging on its own silver stand. Wooden shoe trees that kept his saddle shoes from ever developing a personality of their own. The glass ashtray on Lincoln’s dresser commemorating the Rancho Esperanza Country Club Seniors’ Tennis Tournament, with Chicky’s father’s name engraved on the sterling silver rim. It held coins, white golf tees, and a yellowed ivory pocketknife I must have opened a hundred times just to run my thumb across the blade. I was trying to figure out what it was to be a man, I suppose, and was looking for clues anywhere I could find them. It certainly wasn’t in their bedroom, where the twin beds were covered with pink-and-white flowered spreads and heavy linen sheets that Rosa, the maid, pressed in the mangle that took up half the laundry room. The only place I found any real evidence of Lincoln’s manhood was right back in the kitchen. Here the freezer was stocked with wild ducks he had shot --- mallards, teals, sprigs, gadwalls, and “spoonies” --- preserved in gallon milk cartons with masking tape labels, and filled to the brim with frozen water to prevent freezer burn.

The Crowells took the sporting life seriously, incorporating it emphatically into their home décor. Both sides of the wide hallway leading into the mahogany-paneled dining room were lined with English prints celebrating the hunt. The intelligent, alert, purebred eyes of those silently braying packs tracked me as I moved through the empty house, tingling with the thrill of trespassing. I read and reread the curious description under each engraving: Pheasant shooting --- La Chasse aux faisans. “Get Away Forrard.” Breaking Covey. Anxious Moments. Antique hunting dog portrait plates were arranged on the wall above the dining room sideboard. In other rooms, all available wall space was taken up with richly framed paintings of hounds, spaniels, setters, and terriers. If all this canine imagery wasn’t sufficient to convey the household’s devotion to their four-legged friends, on every fireplace mantel and bookshelf sat pairs of Victorian Staffordshire spaniels --- posing ceramic versions of Best in Show.

The mood of the place was enlivened by the Crowells’ “collections” --- proof they felt no need to impress. I’m speaking of Chicky’s snow globes commemorating her various travels, domestic and abroad, and Lincoln’s ducks --- wind-up waddling duckies, rubber duckies, hand-carved wooden decoys, a duck pitcher with parted yellow beak spout, and all sorts of other duckrelated kitsch that could have come right from the little tourist trap of my hometown.

Roaming through that vast house and looking at their things only made me more curious. I used to wish I were invisible so I could follow the Crowells through each and every room and see what actually took place in their cushioned lives. I wanted to know what they talked about when they sat on the terrace with a cocktail in the cool of the evening, watching the deer shyly pick their way out of the redwood grove to drink at the pond.

I wasn’t the only one who was curious. Even people who have money are intrigued by people who have more money. This revelation took place at the local YMCA, where my mother thought I should go to be around men who might serve as role models. On my first visit, I found myself in the Jacuzzi sandwiched between two bosomy old guys in ballooning bathing suits who were boasting to each other about how much money their sons made. I piped up and mentioned I lived at the old Stokes estate because I thought it conferred a special status on me. “I hear they have a full-time staff of six,” one of them said. The other asked me if it was true that they dressed for dinner every night. I had no idea what “dressing for dinner” meant. Only years later did I realize he probably didn’t either, and that it was the old guy’s assumption of how Old Money lived that had prompted the question.

Some of what I knew about the Crowells’ personal taste I had gotten from my mother, who confided some of Chicky’s dictates. Although they were inconsequential matronly matters, inexperience led me to believe they were the Rules of the Rich: Never have yellow flowers in your garden. Always dry pillowcases in the sun. It’s vulgar for women to wear jewelry during the day, except pearls. Serve brown toast for breakfast and white rolls for dinner. Ladies use nail buffing cream, not colored nail polish. Candles, bedding, and napkins should only be white or ecru. Never break bread with the help. Never.

Because my mother was well-spoken and white, Mrs. Crowell treated her with a lot more discretion than she used with the head gardener or his wife. Manuel and Rosa lived in the Santa Lucia Valley, a few miles from the little Danish outpost where my mother and I had lived, and every weekday morning they drove over the mountain in Manny’s old Ford truck, arriving at the estate at seven-thirty. More than once Chicky told my mother she would no longer allow Mexican couples to live on the property because their Catholicism kept them from exercising birth control and good-common-sense. “They have too many babies and they turn the gardener’s cottage into a little Tijuana. You’ve got to be firm with them, like children,” she’d say, “or they’ll just-keep-multiplying.” In a town that had seen its share of eccentrics, Chicky was known for her impolitic declarations and, like everyone who dealt with her, Lincoln took the path of least resistance.

Excerpted from We Are Rich © Copyright 2012 by Dori Carter. Reprinted with permission by Other Press. All rights reserved.

We Are Rich

- hardcover: 208 pages

- Publisher: Other Press

- ISBN-10: 159051307X

- ISBN-13: 9781590513071