Excerpt

Excerpt

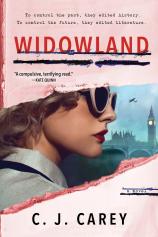

Widowland

Chapter One

Monday, April 12, 1953

A biting east wind lifted the flags on the government buildings in a listless parody of celebration. All the way from Trafalgar Square and down Whitehall, they rippled and stirred, turning the dingy ministerial blocks into a river of arterial red. The splash of scarlet sat savagely on London’s watercolor cityscape: on the dirt-darkened Victorian facades and dappled stone of Horse Guards, the russet Tudor buildings and ruddy-bricked reaches of Holborn, and around the Temple’s closeted, medieval squares. It was a sharp, commanding shout of color that smothered the city’s ancient grays and browns and obliterated its subtleties of ochre and rose.

The big day was approaching, and there seemed no end to the festivities. All along the Thames, decorations were being hung. Bunting was entwined between the plane trees, and ribbons twisted through the Victorian wrought iron railings of the Embankment. The House of Commons itself was decked out like a dowager queen in a flutter of pennants and flags.

Every shop window had posted its picture of the King and Queen, tastefully framed, and every taxi that passed up Whitehall had a patriotic streamer dancing on its prow.

Flags were nothing new in the Protectorate. When the Anglo-Saxon Alliance was first formed, its emblem—a black A on a red background—was emblazoned on every building. No sooner were they run up the poles, however, than the flags were vandalized, ripped to ribbons and left in puddles in the street. Disrespecting or damaging the flag was swiftly made an act of treason, punishable by death, and the order came down that people found guilty of tampering should be hanged from the same flagpole that they had attacked—a deterrent that was as grisly as it was ineffective. After the first shock, Londoners took as much notice of the bodies suspended above them as their forebears had taken of the heads that used to be stuck on spikes on London Bridge.

But that was then.

A lot can change in thirteen years.

It had been threatening a downpour all day. The chill in the air and the absence of anything cheerful to look at meant people shrouded their faces with scarves and huddled in their coats, keeping their eyes down, skirting the craters in the potholed roads. March winds and April showers bring forth May flowers. Wasn’t that how the saying went? Judging by the regular deluges that had drenched the past few weeks, April was certainly shaping up to be a traditional English spring. At least (as some older people thought) there was something traditional about it.

High above Whitehall, in a block that had once been the War Office, Rose Ransom stared down at the tops of the buses and the heads of the pedestrians below. She was a solemn-looking woman of twenty-nine. Her eyes were dreamy and her face, poised above the typewriter, was pensive, as though she were seeking inspiration for the page she was composing, though nothing could be further from the truth. Rose was fortunate enough to possess the kind of physiognomy that gave nothing away. It was an untroubled demeanor, not so much beautiful as enigmatic, a perfect oval framed by neat dark blond hair and grave eyes of indeterminate blue, like a lake that reflects back precisely the color of the sky. From her mother, she had inherited a smooth, unlined complexion that meant she could pass for a decade younger, and from her father an air of unreadable composure that belied whatever turmoil stirred within.

“Come and see this, Rosie! It’s amazing!”

Rose turned. Across the office, a commotion was going on, and Helena Bishop, a lively blond, was predictably at the center of it. Any event was enough to distract most office workers, but that day’s novelty was exceptional. A pair of technicians had wheeled in a squat box of wooden veneer encasing a bulbous fisheye of screen with two dials set beneath. Once a technician had plugged in the set and switched it on, the glass spattered with static before brightening to a monochrome glow. A murmur of excitement went up as every worker abandoned their desk and crowded around, nudging and jostling to get a better view of the tiny screen.

Like most people in the English territories, they had never seen a television close up before and were eager to get a good look.

At first it was nothing more than a snowstorm, but after warming up, a picture emerged, sliding upwards in horizontal lines until someone twiddled the tuning button and it shuddered to a stop.

“Would you look at that!”

The entire office was transfixed. The murky image resolved into a man in evening dress, reading aloud with patrician jollity.

“Anticipation is mounting in London as the first crowds begin to line the coronation route. Early birds are pitching their tents to ensure they get the best view of the royal couple as they make their way from the Abbey.”

All across the nation, the same scene was being played out. The coronation of Edward VIII and Queen Wallis was scheduled for May 2, and the government had announced that every citizen in the land would have access to a television to watch it. To that end, thousands of sets had been installed: in workplaces, factories, and public houses. In schools, offices, and shops. For the first time in thirteen years, every adult and child had been given a day off to see the royal couple crowned. There was more than a fortnight until the big day, but excitement was already at a fever pitch.

“Come on, Rosie!”

Rose grinned across at Helena with appropriate enthusiasm and shook her head. In a split-second calculation, she judged it safer to linger at her desk rather than join her colleagues across the room. She bent over the typewriter and pretended to write.

Television was nothing exciting to Rose. Unlike the others, she had seen plenty of TV sets close up, due to her friendship with the assistant culture minister, Martin Kreuz. Friendship with Martin meant not only television shows but entry to special access exhibitions and theatrical premieres. Art exhibitions at the top galleries. VIP parties and meals out. Martin Kreuz may have been Rose’s superior and twenty years her senior, but he was a cultured man and endlessly generous in sharing the benefits of his position with her. There were numerous advantages to knowing him.

And the disadvantages? She tried not to think about them.

Her gaze drifted restlessly back through the barred and smeared windows to the street outside. The Chamber of Culture itself was a monstrosity, scabrous with soot and girdled with an iron fence laced with barbed wire, but a few meters along from the ministry, the Palladian columns of the Banqueting House retained something of their original dignity. This was the place where, as every schoolchild knew, three hundred years previously, Charles I had been beheaded. The famous occasion when the English killed their king was on every school curriculum, and the place was constantly beset by throngs of kids milling around as their teachers held forth, chatting among themselves and pricking up their ears for details of the beheading.

Some of the nation’s more recent rulers, King George VI, his queen, Elizabeth, their two daughters, and a rabble of minor royals had been accorded far less ceremony in their demise. But as far as Rose was aware, no child learned their fate in school.

Most people had no idea what had become of them. Or cared.

It was Protector Rosenberg who featured in the history lessons now. The Leader’s oldest friend, who had been with him in the beer halls and marched alongside him in the earliest days of the movement. The man dubbed the Leader’s Delegate for Spiritual and Ideological Training, who had guided and shaped the development of the Party, its philosophy and its ideals. The thinker who embodied the Party’s connection to the past and the future. Rosenberg was a visionary, and when the Leader made him Protector, he had resolved that his dream of a perfect society would find its ultimate expression in England.

Now, more than a decade later, Rosenberg’s vision was complete. A whole generation who had never known anything but the Alliance was growing up. German came as easily as English to their lips. As Martin was so used to explaining, the Alliance was the perfect fruition of the history of the Anglo-Saxon peoples. In a way, he liked to say, it was the “end of history.” The ultimate “special relationship.” Two peoples who had once been a single race had come together again in a seamless join.

As neatly as if King Charles’s head was restored to his body.

Not that anyone cared about history. The only thing that mattered was that order was restored, and whatever people thought of that order, it meant that life ran smoothly. Food appeared on the table, and the buses and trams arrived on time. The blossom on the horse chestnuts in Green Park turned up as punctually as ever and birds still sang each spring.

“I see the march of technology leaves you unmoved.”

The sardonic voice emerged from Oliver Ellis, who occupied the desk next to Rose. He had a dark, unruly shock of hair, a brooding demeanor to match, and a wit that was acid enough to eat through shrapnel. Generally, Rose appreciated Oliver’s barbs; they were mostly aimed at hapless colleagues or at diktats of more than usual idiocy from the culture minister’s office. But sometimes, she guessed, she must be the target of his humor too.

That was how men like Oliver worked.

He stood up, adjusted his horn-rimmed spectacles, and frowned. “Aren’t you coming to look at our marvel?”

“I’ve seen a television already,” she replied coolly, adjusting the paper in her typewriter.

“Of course you have. I forgot. Friends in high places.”

He followed her gaze out the window, where it was raining harder and pedestrians were raising their umbrellas against the sky, as though seeking protection from something fiercer than an English spring.

“God forbid it rains on the big day.”

“There ought to be a law against it,” said Rose.

“Probably is.” Oliver unhooked his jacket from his chair and pulled it on. “Alliance regulation number 8,651. Prohibition of Precipitation on coronation.”

She smiled. “SS Stipulations on Sunshine Standards.”

“Rain Restrictions Regarding Royalty,” he countered.

She couldn’t stop herself laughing. Oliver was good with words. But they all were.

That was why they were here.

Oliver had been an undergraduate at Cambridge before the war, and when the fighting began, he was given a desk job in the old dispensation that meant he missed any action and survived to serve the new regime. Men of Oliver’s type were unusual. Many males between seventeen and thirty-five who hadn’t died resisting the Alliance had been sent to work abroad, causing a notable gender imbalance in England.

The country now had two women for every man.

Perhaps this was why, as the Leader put it, “Women are the most important citizens in this land.” And lest anyone forget, his comment was carved into the pediment of a vast bronze statue erected on the northern end of Westminster Bridge.

It was an impressive installation. Where once the chariot of Boudicca had stood, now the Valkyrie figure of the Leader’s niece Geli was planted, heavy thighs draped in a classical toga, head encircled with a laurel crown, staring broodily out at the muddy waters of the Thames. Just as France had its Madeleine—a representation of perfect womanhood—England had her Geli. Geli was young, intelligent, talented, and beautiful. She symbolized everything that was fine about femininity. She was the apogee of womanhood. In essence, she embodied the spirit of England.

Just a shame the woman had never set eyes on the place.

“You don’t want to miss this, Rose!”

Helena’s excitement was contagious. All around her, more Culture Ministry staff were emerging from their offices and cubicles—her friends in the Film Division, girls from the Astrology Office, young men from Advertising in their braces and red ties, Press Department staffers, a gaggle of people from Broadcasting, even some stragglers from Theater and Art, who were relegated to a couple of back offices on one of the building’s lower floors.

Rose was about to give in and join them when from across the office, she became aware of a Leni bustling toward her desk with an air of self-importance. She was a dumpy, matronly figure, steel hair gripped into a bun and an upper lip disfigured by a badly mended cleft palate. She wore no makeup—she wouldn’t dare—but her cheeks were flushed with a bright disc of pink, and her eyes glinted in the fleshy folds of her face. Encased in thick wool stockings and a pewter-gray suit in the kind of crusty, hard-wearing tweed favored by her type, she might have been a crab, scuttling toward her prey, carrying a clipboard pincer-style. Generally Lenis believed themselves to be the essential cogs of any factory or workplace, and no matter how low level their actual function, they regarded themselves as the glue that kept the economy running. They were probably right. There was plenty of drudge work in the current administration, and it required an army of women to carry it out.

This woman, Sheila, had a desk right outside the minister’s office and believed she knew everything that was going on in the ministry. She smiled blandly as she sighted Rose, certain that the message she was conveying would bring a shiver down anyone’s spine.

Rose steeled herself, summoned an expression of polite inquiry, and refused to turn a hair.

“Ah, Miss Ransom. An important memo for you.” Sheila detached a piece of paper from the clipboard and floated it onto Rose’s desk. “The minister wants to see you. He’s away at the moment, but he’s back on Friday. You’ll report to him first thing.”

She leaned closer, bringing a waft of unwashed clothes and cheap perfume.

“Little word of advice. Be punctual. In fact, I recommend you arrive ten minutes early. The minister despises bad time keepers. He takes a very dim view. And no one likes to see him angry.”

Chapter Two

“Aren’t you excited? I am. I’ve never seen a king crowned. It’s like a fairy tale.”

“Not my kind of fairy tale,” said Rose, wiping a porthole in the window’s condensation and peering out.

The bus was packed and stuffy with tired commuters making their way home. Rose and Helena always shared the journey, and they liked to take seats on the upper deck so they could look down on the passersby. It was a kind of free entertainment, watching the trudging crowds surging up Whitehall in their shabby clothes and worn shoes. They poured like a polluted river up the Strand, the lowly Magdas in their cheap coats and hats, the office working Lenis, with their heels and pencil skirts and buttoned jackets, and the Klaras pushing enormous strollers, usually with a couple of children hanging off the handles. Sometimes a trudging Frieda, encased in compulsory black, scurrying home before her curfew. Widows suited black, because they were, effectively, a form of shadow themselves, the sooty remnants of a married life snuffed out.

The detailed regulations on clothing worked through a system of coupons, with the number of points varying according to caste. Because textile and leather production was geared toward the needs of the mainland, all shoes were made of plastic and rubber, their soles from cork or wood, and most clothes were fashioned from the same rough materials. Yet even with these constraints, it was not hard to distinguish a higher-order woman from her sisters.

The differences between men were more subtle, marked less by appearance than by demeanor. Foreigners carried themselves with a natural confidence and swagger, whereas natives remained buttoned up, modeling their famous stiff upper lip.

On the corner of Adam Street, a group of elderly men rolled out of the pub and deferred obsequiously to a pair of officers monopolizing the sidewalk two abreast.

In a flash, an image came to Rose. Her father, in one of his rages, when the Alliance was first announced.

“It’s a failure of leadership. We were led by fools and charlatans. No wonder we caved in so quickly with leaders like ours.”

Her mother, white-faced and flustered, explaining that Dad was ill and didn’t know what he was saying.

The chief advantage of the bus journey was that it offered the chance for Rose and Helena to talk out of earshot of their office colleagues. You could never talk completely freely, because surveillance was notoriously easy to carry out on public transport, and watchers were hard to spot, so it was as well to shoot a look over the shoulder before speaking. But the Leni behind them—plain with plaits and thick spectacles—was buried in a paperback called A Soldier’s Love, and the two Magdas on the other side, their hair tucked under turbans, were engaged in fervent bitchery about a friend.

Helena rolled her eyes.

“I forgot. You’re the expert on fairy tales. How’s it going?”

“Fine. Fairy stories are easy really. Better than the Brontës.”

“I don’t know what you’re complaining about. I’d kill for your job.”

“Says the girl who goes to every movie premiere in the land.”

“I know it sounds fun, but you can’t relax. I’m there to check inaccuracies. Anything that’s slipped through the net. If political errors remain, it’s on my watch. Imagine how stressful that feels. I’m not just sitting back eating chocolate.”

“Chocolate. I remember that.”

Helena grinned. It was as though she could not help the good humor shining out of her. Everything from the milky blond tendrils spilling from her hat to the smile always hovering at the edges of her mouth was irrepressible. Short of being German, Helena had been gifted with all the blessings the gods could bestow, chief among them a sense of the ridiculous—a vital attribute in government service.

“Don’t tell me Assistant Minister Kreuz doesn’t bring you back chocolate from all those foreign trips he makes. I bet he has huge boxes tied with satin ribbon hidden in that briefcase of his.”

“Don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Oh, come on. Give me credit for having eyes in my head.”

“And?”

“He adores you. I’ve seen him around you. You’d have to be blind to miss it. And I know full well you’re mad about him too.” She gave Rose a gentle nudge with her elbow. “I can keep a secret, you know, Rosie. We are best friends, remember?”

The bus shuddered to a sudden halt. Peering out, Rose saw a series of army vans blockading Waterloo Bridge. White tape had been hoisted across the carriageway, and a policeman was directing traffic with officious semaphore, as though conducting an especially bracing marching band.

“There’s been an incident,” murmured Helena.

“Where?”

Helena checked swiftly over her shoulder.

“In the office, they were saying it was the Rosenberg Institute. It happened right in the middle of a classification procedure. As if that’s not nerve-racking enough. Remember?”

Back in the early days of the Alliance, shortly after the Time of Resistance, every female in the land over the age of fourteen had received a letter summoning her for classification. The procedures were staggered to cope with the numbers, but in the event, the processing of more than half the population was carried out with military efficiency. Sixteen-year-old Rose, along with thousands of others, had reported one Saturday to the Alfred Rosenberg Institute, the former County Hall, on the South Bank of the Thames.

It was a bright, sunny morning, and the consignment of women being processed that day was held in a strict line that snaked out of the building and all the way across Waterloo Bridge. Guards with dogs patrolled, and Rose noticed the younger men staring hungrily at one girl about her own age, whose beauty and natural confidence marked her out. She had the glossy, pedigree beauty of a racehorse, with long, slender legs, wide-set, pale-blue eyes, gleaming hair, and a light dusting of freckles. She was tossing her head, aware of the men’s glances and knowing her looks were precisely the kind that the regime loved. They called such attributes Nordic—the highest praise—and Rose had no doubt that her neighbor would be instantly assigned to the top caste.

For a moment, she had considered hanging back, in case proximity to this beautiful girl affected her own chances, before she checked herself. Systems in the Alliance never worked on whim. The Rosenberg Assessment Procedure was scientifically rigorous, and in case of doubt, the institute’s walls were plastered with charts showing precise comparative measurements of head size, nose shape, and eye color for each different racial type. Every tiny calibration would be translated into a precise position on the scale of caste, with further gradations between divisions, from Anglo-Saxon Alliance, or ASA, Female Class I (a) to ASA Female Class VI (c).

The method had been trialed in Germany and was highly reliable. There, since 1935, people had been measured, not only to distinguish between Aryans and other races but also to assess young women who wanted to marry into the SS. There was no reason at all why the practice should not be expanded to classify an entire female population.

No amount of reasoning, however, helped when the procedure itself made every woman flinch.

First, the craniometrist fitted a steel device like a giant claw around their heads and assessed their other dimensions with a series of metal rods. Then the anthropometrist, seated between a tray of glass eyes in sixty shades and an array of sightless plaster skulls that looked uncomfortably like death masks, measured the angles of their jaws and noses and brows and noted them down. The endless queues of women shuffled slowly through a hall pungent with a school gym smell of sweat, unwashed clothing, and fear.

When it was the pretty blond’s turn to have her profile measured with a contraption that looked like a pair of giant compasses, she rolled her eyes at Rose, and it was all Rose could do not to giggle. The girl seemed to brim with anarchic hilarity and mischief, as if the two of them were sharing some outrageous private joke. Amid the tense and nervous throng of women filing through the packed hall, proximity to this larky woman seemed the best way to get through the ordeal.

Charting every facial feature, then weighing and measuring each female took a good half hour, after which they all trudged into an adjoining hall to face the second level of selection: the questionnaire. This required them to provide a host of information about their family, their ancestry, past health and mental conditions. Eventually, when all the boxes had been ticked, the women were assigned the classification that accorded with their heritage, reproductive status, and racial characteristics. This label would determine every aspect of their lives, from where they should live to what clothes they would wear, what entertainment they could enjoy, and how many calories they could consume.

Although each classification had its official title, nobody bothered with a mouthful like ASA Female Class II (b) when they could use the inevitable nicknames. Members of the first—and elite—caste were popularly called Geli Girls after the woman most loved by the Leader, his niece Geli. Klaras—after the Leader’s mother—were fertile women who had produced, ideally, four or more children. Lenis were professional women, such as office workers and actresses, after Leni Riefenstahl, the regime’s chief film director. Paulas, named after the Leader’s half-sister, were in the caring professions, teachers and nurses, whereas Magdas were lowly shop and factory employees and Gretls did the grunt work as kitchen and domestic staff. A range of other designations existed—for nuns, disabled mothers, and midwives—but right at the bottom of the hierarchy came the category called Friedas. It was a diminutive of the nickname Friedhöfsfrauen—cemetery women. These were widows and spinsters over fifty who had no children and no reproductive purpose and who did not serve a man.

There was nothing lower than that.

Many of these classifications changed, as women became mothers, for instance, or failed to. Women were regularly screened, and an entire division of the Women’s Service was devoted to the business of reassessments. Yet in a way, the labels became self-fulfilling. Certain occupations favored a particular class of female. Poorer food, clothes, and housing reinforced women’s differences. Without meat, fresh fruit, and vegetables, Friedas and Gretls grew sickly, and their complexions dulled. Deference became second nature. No one needed to ask if a woman was a Leni or a Gretl or a Magda, because you could tell at a glance. And a Geli, whose rations and work were enough to put a spring in her step, would always walk taller and hold her head that little bit higher.

A Geli card was the golden ticket.

When the two girls left that day with ID marking them as ASA Female Class I (a), Rose’s new friend locked arms with her and gave a little spontaneous whoop.

“I’m Helena Bishop. How about we go and get our pictures taken?”

It was becoming a tradition, among young women classified as Gelis, to have their photographs taken beneath the statue of the original Geli that had been newly erected on the Embankment. Photographers had set up shop there, with instant cameras, producing Classification Day pictures on request.

“OK then.”

The two girls were friends from that day onward.

Yet Rose and Helena were the lucky ones. Some young women, having their life chances radically diminished by classification, abandoned common sense and created mayhem, weeping, screaming, and attacking the guards. Such hysterics were always hustled quickly away, to have their caste downgraded yet again on account of antisocial behavior.

The bus lurched forward again, leaving the traffic jam behind.

“So this incident, what happened?” asked Rose quietly. “Was it a girl?”

“A man, apparently. Walked in quite calmly and shot one of the guards.”

“An angry father?”

“No.”

“Who then?”

“I heard it was, you know…one of Them.” Helena jumped up and grabbed her bag, as though relieved to have reached her stop. “Better get going! See you tomorrow!”

All eyes followed her hourglass figure as she sashayed her way down the stairs.

Two stops later, the bus came to a halt, and Rose made her own way into the shadowy streets.

Although street lighting was installed in elite zones, its hours of operation were strictly limited, and it would be another few hours before the dim wattage of the lamps, haloed in the evening mist, pierced the murk. Rose didn’t mind. It wasn’t quite dusk, and besides, she preferred shadows. They obscured the everyday gloominess of the streets—the potholed pavements, cracked windowpanes, and pallid, malnourished faces—and in the crepuscular light, the dirt-darkened brick buildings and cobbled alleys had a historic feel. The fanlights above ancient, narrow doors and the glint of stained glass transported her to a different age. Sometimes she allowed herself to fantasize that she was going back in time, before the Alliance, even to Victorian times.

Instantly, she checked herself.

Nostalgie Kriminalität. Nostalgia crime. Any suggestion that the past was better than the future was strictly outlawed. Sentimentality Is the Enemy of Progress. Memory Is Treachery. The mottoes every half-diligent schoolchild knew by heart.

Citizens of the Alliance were not encouraged to think about the past, except in the way that the Protector wanted them to think of it, as a mythical story. History with a capital H, like something out of the Bible.

When Rose was first allocated housing in Bloomsbury, the name sounded curiously familiar, and it was a few moments before she registered why. Then she remembered that the name had once belonged to the Bloomsbury group, a circle of subversives who had lived here some decades before, producing degenerate art. From what she knew, their ringleaders had been arrested early in the Alliance and their homes turned over to elite citizens.

Which fortunately included herself.

A blast of stale beer and light emanated from a pub, and a couple of Magdas approached, their exchanges brittle on the evening air.

“She says she can’t find a man for love nor money. I said, why don’t you get a transfer to the mainland? There’s plenty of choice for your sort there. You wouldn’t believe the look she give me.”

They dropped their conversation instinctively as they drew level with Rose and, with obligatory deference, gave way to let her pass.

Rose pushed open the door to her block. The hall was floored with linoleum, and to one side stood a shabby deal dresser strewn with a haphazard collection of letters and leaflets. A notice pinned to the wall declared Females Class III to VI inclusive are forbidden entry to this premises after 6 p.m. A sour smell hung in the air, and instinctively she tried to separate out its components, detecting alongside the usual cabbage and floor polish a tang of vinegar and a top note of oily fish. That was a dangerous smell. In the absence of meat, citizens were sometimes tempted to catch their supper in the Thames—unauthorized fishing was prohibited, but hunger and the need to supplement meager rations were often enough to drive amateur anglers to try their luck under cover of darkness. Generally, they were picked off by the patrols who waited in the arches of the bridges or concealed by riverbank trees, and their corpses would be found floating alongside the other detritus of society—suicides, desperate women, drunks. But if they returned and cooked their catch, there was still the chance that a vigilant neighbor or caretaker would detect the crime by odor alone.

Snapping on the light, Rose shut the door behind her and leaned against it, looking around. Her room was simple. A bed, a chair, and a small partitioned section for a kitchen stove and cooking ring. Tattered photographs of London in the Time Before: a leafy square with smart railings, cheerful shopfronts, and a street scene featuring vans painted with advertisements for Bovril, Hovis, and Tetley Tea. A worn orange rag rug lay before the gas fire. And against the window, a rickety, wood-wormed desk looked down over the tops of the plane trees in Gordon Square.

The furniture was cheap. Like food and clothing and everything else, it was made of the least valuable materials. The best cuts of wood—the oak, ash, and cherry—were needed elsewhere on the mainland, together with the highest-quality food and building materials. Citizens of the Alliance had to make do.

Rose didn’t care. This was a room of her own, and she knew how lucky she was to have it.

Retrieving the tea bag she had left out that morning to dry, she set a kettle on the stove. Once she had made a cup of tea, she fed an Alliance mark into the gas meter, kicked off her heels, and drew her legs beneath her in the armchair.

It was only when she was gazing into the cracked bars as they flickered violet, then gently glowed, that she finally allowed her mind to focus on the question that had been haunting her like an ill-concealed shadow.

What did the culture minister want with her?

Foul-mouthed, florid, fifty, and prone to random acts of spite, Minister Hermann Eckberg had a vile temper that was partly the gift of genes and partly the legacy of a horse-riding accident in Hyde Park that had wrecked his back and for which he held the whole of England responsible.

As culture minister for the Protectorate, Eckberg reported directly to Joseph Goebbels, the controller of all culture back in Berlin. Since SS Reichsführer Himmler had been promoted to deputy Leader, following the defection of the traitor Goering to Russia in 1945, the Culture Ministry was seeded with SS men, and they were not a natural fit. Eckberg in particular loathed his job. As an unashamed Philistine, he detested art and music, let alone literature or theater, and like the Romans before him viewed England as a distant outpost of empire. The food was disgusting, the weather worse, and the political circumstances surrounding the Alliance meant that employees had to be treated with a veneer of respect that was not accorded the citizens of other subjugated nations.

All of which was enough to put Eckberg in a perennially bad mood.

Rose had a deep, panicky urge to call Martin. She imagined his handsome face, reassuring her, like a kind family doctor. His smooth tones and his husky voice with its attractive German edge. So she had been summoned for a meeting? Why worry about that? It was not as if she had been stealing paper clips, for God’s sake. What possible grounds could an innocent person have to fear?

She lifted a hand toward the telephone, then immediately dropped it. Not only had Martin forbidden her from contacting him by telephone, but he was away on a trip abroad and not back for two days.

Besides, something told her that the summons concerned Martin himself.

Widowland

- Genres: Dystopian, Fiction, Historical Fiction, Historical Thriller, Suspense, Thriller

- paperback: 432 pages

- Publisher: Sourcebooks Landmark

- ISBN-10: 1728248442

- ISBN-13: 9781728248448