Interview: October 28, 2015

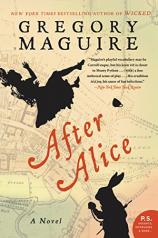

Gregory Maguire is no stranger to rewriting classic children’s fairy tales for adults. His first try was an overwhelming success; WICKED --- a vividly realized revisionist take on L. Frank Baum’s THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ --- was adapted into one of the most popular Broadway shows of all time. Now he returns with AFTER ALICE, a magical new twist on ALICE'S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND, which was recently published to coincide with the 150th anniversary of Lewis Carroll’s beloved classic. In this interview with The Book Report Network’s Bronwyn Miller, Maguire discusses what interests him about rewriting children’s stories and how he chooses his subject matter. He also talks about the importance of books in children’s lives --- a subject he is deeply passionate about --- and how he’s careful to avoid a fistfight with Harper Lee.

The Book Report Network: You are one busy author --- writing in many different genres and for many different age groups --- but you’re best known for your revisionist takes on classic fairy tales, such as WICKED and MIRROR MIRROR, to name but two. What first drew you to writing your own take on fairy tales?

Gregory Maguire: The older I get, the more I see that writing is really just an extension of playing. The kind when we were all too young to go outside on a rainy Saturday afternoon, and TV was either boring or verboten (or both). And we were too young to read, and it was before the internet had arisen to ensnarl us all. I’m talking little kids on the floor, with trucks and little plastic guys and fallen spoons and the pattern in the carpet…. Everything had a use, everything was up for grabs, everything was OURS. I think I felt about story the same way that I felt about toys at the bottom of the toy box, or stones in the backyard, or bird feathers on the sidewalk. Found objects. Opportunity for inventing. Writing still feels to me like making order out of the disorderly world, and as fairy tales were among the earliest stories I got, those are the ones I am the most used to playing with.

TBRN: Are the books to which you decide to give a new spin the ones that had the greatest impact on you as a child? What books have you shared with your children?

GM: There are many books that actually had MORE impact on me as a kid, but they are still under copyright…including HARRIET THE SPY, A WRINKLE IN TIME, the Narnia books, etc. But also, as they are more modern, they feel more “finished,” and I don’t have the same sense of their availability for fiddling around with. I mean aesthetically, not legally.

My own kids are children of the aforementioned Internet Interregnum (I do hope it is temporary and a return to a word-based culture is in our future). Therefore, the books we were able to share with them are the younger ones --- picture books like Maurice Sendak’s and the Tintin books. I did read them THE LION, THE WITCH, AND THE WARDROBE, but by about chapter four of THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS, I had lost them all for several decades. Bad parenting on my part.

TBRN: You’ve also written a number of realistic/contemporary novels for teens (MISSING SISTERS, THE GOOD LIAR, OASIS). How does the process of writing one of these books differ from writing one of the Wicked novels?

GM: Two of the three novels you mention are also “historic” these days --- though the definition of historic changes by the person speaking. (MISSING SISTERS takes place in the 1960s, during my childhood years, and THE GOOD LIAR largely takes place during World War II, which was before I was born). Come to think of it, OASIS takes place in the early 1990s, before the Internet Inquisition, so that’s probably a historical novel to current kids. I mention that designation because I think contemporary (as opposed to realistic) is a slippery concept, and increasingly I feel myself outdated even if I am still alive. Realistic, though --- that is an approach of the mind. I think one has to write realism so real that it seems fantastic, and fantastic so fantastic that it seems real. So the difference really boils down to which shoes you put on as you shuffle to the typewriter: your mud-caked work boots or the fancy Aladdin-slippers with the curly points and little jingle bells. The slippers are better for approaching to write realism, the boots for fantasy.

TBRN: In the early days of writing AFTER ALICE, how did you decide to focus on the stories of Ada and Lydia, rather than one of the inhabitants of Wonderland? What drew you to Lewis Carroll’s classic tale in the first place?

GM: I wanted not to go very near Alice, who seems to me an almost perfect fictional character in that she is transparent, nuanced and fluid. To tell the “secrets of Alice” --- what hubris! She had a blocked sinus? She was a closet revolutionary? She was color-blind? No --- I wanted to leave Alice as very nearly alone as I could manage, while honoring her as one of the great heroines of world literature all the while. But Lewis Carroll said almost nothing about the older sister --- not even her name --- and only made one reference to Ada. So I felt I was within my rights to embroider upon those two inventions of Carroll without fear of being called by the Libel Department of some major law firm representing Lewis Carroll’s heirs and assigns.

As to Wonderland (and Looking-Glass land, which are different names for the same place, I always thought), I found those locations more frightening than charming, more Kafka than Kipling. More Purgatorio than Shangri-La. I found it frightening as a child --- a baby who turns into a pig and runs away into a forest, and no one seems to care! --- and so I thought at the ripe-old age of nearing Medicare, it was time to face my demons and take a visit for myself.

TBRN: There’s a wonderful line in Chapter 14 about how stories have their own intentions that may differ from those of the reader. What was your intention when you started writing AFTER ALICE? Did it change by the time you finished?

GM: I will admit that I tried very hard (in the spirit of Lewis Carroll) to let Wonderland unfold as it would, and not to try to overlay it with too many associations that would tip my hand. In other words (my, I’m full of comparisons today), I wanted to do a Jackson Pollock of a plot, to let it wander and to suggest to readers what it might, instead of to “carry” my own dedicated meanings. I only partly succeeded. Once Siam Winter comes into the story --- I finally find a way to integrate the all-white world of Wonderland! --- the story takes on a deeper set of possible meanings about the dangers of the imagination, as well as its blandishments and benefits.

TBRN: How much research did you do for this novel? And how many times did you revisit Lewis Carroll’s text?

GM: About two years ago, I flipped through the 24 chapters of the two Alice books and made a list of characters who appeared in each one. I didn’t actually read the books again. I knew that Carroll was saying a great deal about the mutability of childhood and the mutability of dream-experience, and so it didn’t matter if my references to characters weren’t colored exactly within the lines that Carroll had originally drawn. Odd, then, that once I was done and went back, I found I had hit the mark pretty well without even trying. It felt as if I had been doing ventriloquism without trying. Even as to the characters --- I never looked back and checked off which characters I had used and which I had not bothered with, but in fact nearly all the important ones came up and presented themselves to me as I wrote. Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee are the exception; I’d have liked to see more of them. They must have been away on business.

TBRN: Do you feel a certain responsibility when writing for well-known characters of literature such as Alice, or the characters in MIRROR MIRROR or MATCHLESS, inspired by Hans Christian Andersen’s THE LITTLE MATCH GIRL?

GM: Indeed I do. My hope is never to besmirch the original, but only to add to it, to redesign its setting so it shows up in a new light. Perhaps my Dorothy is a bit prim and self-admiring, at the end of WICKED (and even more so in OUT OF OZ), but she is also good-natured and forward-thinking as Baum (and Judy Garland) shows us. I think of it as taking a venerable old jewel and, without re-cutting it, trying to fashion a new setting or housing in which it can show again, perhaps for a new eye, to better advantage.

TBRN: Your bestselling novel WICKED was adapted into one of the most successful Broadway musicals in history. How involved were you in the process of taking it from the page to the stage? Were you surprised at its enormous success? Which of your other novels do you think might make a good musical?

GM: I have written extensively about this elsewhere, but I will say I made it a point of honor to liberate the story of WICKED from page to stage and then --- once I had been assured that the hearts and minds of the Broadway creative team were sound --- to stand aside and out of their way and let them do their work unimpeded. (As I had done mine, on WICKED, the ghost of L. Frank Baum never showing up once to castigate me.) Yes, I was hugely surprised at the success of “Wicked” the musical. I saw it about five times in the first 10 days it played because I was afraid it would close after 12 days, and I wanted to be able to remember it as well as possible. This month it will have been running on Broadway for 12 years. I rather underestimated it, and perhaps my own work as well. I’ll take that up with my therapist behind closed doors.

TBRN: Have you ever been tempted to do a reimaging of a more adult classic, say TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD, or would that be a rights-issue nightmare? It could be fascinating to hear the story from Boo’s perspective.

GM: I’ve always worked on stories in the public domain. And, frankly, I think I can understand the European and the British 19th-century mindset better than I can that of the American South. I mean no disrespect in that comment --- the U.S. is many different countries cobbled together, and I’ve spent more time in London and Paris and Greece and Italy than I have in Atlanta or Georgia or Louisiana. (Of writers, though, I am a huge fan of Truman Capote and Harper Lee and Eudora Welty and Faulkner. And as a kid I loved Margaret Mitchell.) Meanwhile, to close this question, Harper Lee has just released her own reimagining of TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD, sort of, and I wouldn’t want to get in a fistfight with Harper Lee.

TBRN: You are the founder and co-director of the National Children’s Book and Literary Alliance. Can you tell us about this organization and what it does?

GM: I think you mean “founder and co-director of Children’s Literature New England, Inc.” I have since resigned as co-director, though I’m still involved. The organization has existed for 27 years to promote awareness of the significance of literature in the lives of children. It does this by helping to highlight for all professionals who work with children and books --- the writers and illustrators and editors, the teachers and librarians --- how books for the young can be genuine works of art, obeying the rules (and breaking the rules, as art does) of aesthetics. Children’s books can reflect changes in social understanding, can promote continuity, can also prophesy. Like all art that is worthy of the name. (Children’s books can also be regrettable, forgettable, palpably pulpable, and sheer and utter rubbish --- as books for adults can, too. The fact of its audience doesn’t make a children’s book art --- it’s the excellence of the talents of its creator, and its creator’s devotion to both truth and to art. Same as for adults. I rest my case, y’r Honor.)

TBRN: What are you working on next?

GM: A fabulous cup of home-brewed coffee, no sugar, two creams.