Excerpt

Excerpt

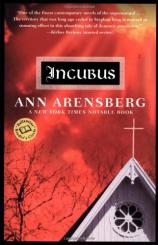

Incubus

CHAPTER ONE

When I sat down to make a record of the Dry Falls happenings, I made many false starts in my attempt to find some logical sequence.

I am a pastor's wife and I can quote from the Book of Revelation, in which my task, or any writer's task, is spelled out plainly: "Write the things which thou hast seen, and the things which are, and the things which shall be hereafter." St. John was the chosen instrument of God. He transcribed his visions in the order in which God sent them. When it came to ordering events, I had no guidance. Many things were happening around us all at once; some I learned about too late for inclusion in this chronicle. I must choose a beginning blindly and with trepidation, as soldiers draw lots to "volunteer" for a suicide mission. I will mix up past and present as it suits my purposes. The future is still uncertain, so I can only guess at it. I was determined to publish my account, have it printed and distributed through the bookshops in my county. By so doing I will be following the mandate to St. John: "Seal not the sayings of the prophecy of this book; for the time is at hand."

I was not qualified to be the narrator of these incidents, although my stake in making them public was very high. I was an amateur whose experience was limited to one topic. I wrote about foodÑgrowing and cooking it--500 words a week, two typewritten pages. My readers in the state of Maine were undemanding. If a measurement was incorrect, they blamed the printers. My readers, after all, were familiar with my subject. They were cooks like me. I thought of them as my colleagues. Many of them sent me their families' favorite recipes. I reprinted the best in a yearly column called "Readers' Choices." I have met my readers at newspaper-sponsored contests. I have spoken at women's clubs from Kennebunk to Machias. Often they were more knowledgeable than I was, and more ambitious. They took courses in cake decoration. They were casual about croquembouches. If they had no need of advice, why did they read me? They cooked three meals a day. They ran out of fresh ideas. They looked to me to make their kitchen chores more interesting. Since I wrote for a newspaper, my words had the ring of authority.

Suppose I were to lecture to these groups of nice women on my present subject? I can picture a setting like so many where I have spoken, a community center, recently the scene of a flower show, trestle tables placed against the walls bearing withering exhibits, entries in various categories, on various themes, such as "Fruits of the Vine," "Table for Two," "Bringing a Meadow Indoors," and "One Perfect Rose." When they were settled on folding chairs with their cups of coffee, I would walk to the front of the room and begin to speak. I would tell them about our town and its time of emergency, about women like themselves whose bodies were used in sleep. I can see them averting their eyes, darting glances at friends, burrowing in their handbags. Two or three who were seated at the back might make a tiptoed exit. Unless I reverted quickly to culinary matters, I would lose my audience along with my credibility. On any issue other than menus and food preparation, my respected regional byline counted for nothing.

For as long as I wrote it, my little column was a link to humanity. It addressed basic needsÑsurvival, nutrition, celebration. It was concerned with the continuance of life from season to season: planting, harvesting, putting food by for the winter. The document I am presently compiling takes up nonhuman matters, events that make hunger and survival seem benign and attractive. I must catalogue human reactions to nonhuman circumstances: fear, depravity, shame, hysteria, self-deception. I am obliged to spare no one, not my loved ones, my acquaintances, my countrymen. I have tracked down participants who were desperate to forget their experience. I have asked the most intimate questions from an impersonal standpoint. Unjustly, since I was as much a sufferer as anyone, the work I am doing will set me apart from my fellows. I am sitting at the desk where I tapped out my column each week, a plank set on two metal cabinets with plenty of drawer space.

The desk is the same, but the room it is placed in is different. In the rectory it sat in one of our three guest rooms (although sometimes I carried my typewriter to the kitchen table). Here it occupies a crowded corner of our only bedroom. The rectory was a fine old house, crowned by a belvedere, with Carpenter's Gothic trim and long French windows, a house that captured and stored the available light. There were many ideal locations for perennial borders: along the proper front walk paved with brick in a herringbone pattern; running the length of the fence by the sidewalk; on either side of the steps by the screened-in back porch. I never dug up the lawn as long as I lived there. I believe that borders should relate to existing structures.

Our new home is a two-story apartment in a white clapboard building on Main Street recently vacated by a chiropractor. Before Dr. Klinger, the building housed a firm of tax accountants; before that, it was a branch of the Huguenot Society of America. We tore down partitions that divided each floor into office cubicles or examining rooms, leaving us with a large open space on the ground floor (living-dining room and efficiency kitchen) and a bedroom, bath, and storage room upstairs. The place is snug, to put a good construction on it, but adequate to our needs.

Over the front doorbell is a discreet brass plaque bearing the name of the Center; but Henry and his employees work underground in the finished basement. The basement has a separate entrance down a half-flight of steps. Except for two high windows, it is lit artificially by rows of overhead fluorescent tubing. There is a washroom, a compact refrigerator, and a two-burner hotplate. The Center's offices and laboratory are self-contained, although we sometimes conduct interviews upstairs in the living room. I should mention that we offer our services free of charge. Many of our clients have been driven out of their homes, lost their jobs, or incurred hospital expenses because of emotional trauma. In the interests of our work we are living in straitened circumstances. Henry inherited money from his father, who made his fortune smoking and canning seafood. Conrad Lieber died when Henry was twenty-three and away at war. Henry rarely touched his legacy when he was a minister. He draws on it now to support the operations of the Center. He still pays himself an Episcopal clergyman's wages, except that a beautiful house and grounds were once part of the benefice.

The landing outside our bedroom is stacked with cartons, the overflow from the storage room. The cartons are filled with boxes of slides and tapes, newspaper clippings, and notes scribbled down at the time on anything handyÑnapkins, deposit slips, the insides of paperback book covers. Each carton is labeled and dated according to incident: the Manning Case, the Burridge Case, the Violette Brook Campgrounds Case, etc. Our bedroom is small, with one logical place for the bed, so my desk must face a wall instead of a window. If my desk faced the window (thereby blocking the major passageway), what would I see through the glass to cheer or please me? Outside there is a concrete yard with a drain in the center and a chain-link fence between us and Baldwin's hardware store. If I stared out the window too long at this sordid view, the gardener in me would take over, or whatever is left of her. A hurricane fence makes an excellent support for a vine gardenÑtomatoes, cucumbers, sweet peas, and a splash of blue morning glories.

Until I finish this chronicle, I am cut off from the natural world. I am living, for the present, in a world of words and abstractions. I am thin, where I used to be sturdy. I have lost my color. I cook by rote, in a hurry, only at suppertime. For the other two meals we open cans, jars, and boxes. We live like students in an off-campus dorm with a communal kitchen. Henry is quite content with these slapdash arrangements. Before we married he subsisted on creamed herring, sardines, and crackers. Sometimes when my back aches from sitting in one position, I invent a new dish in my head, although rarely in practice, such as a cornbread cake made with buttermilk and filled with vegetablesÑstring beans, onions, garlic, red and green peppers. When will I be free to lead a more balanced life? It is more than two years since I put on blue jeans and struggled through the briars on my way up Pumpkin Hill, tearing my sleeves, getting long, mean scratches on my arms, until I found the place where the sweetest wild blueberries were hiding. Did my love for the things of this earth bring on the trouble in the first place? Did my heedless, pink-cheeked vitality attract their notice? Did the smells from my kitchen tempt them out of their element? I am dealing in guilt and blame, which serves no purpose. Every woman in Dry Falls was an unsuspecting magnet. Adele Manning took "baths" in the light of the waxing moon. The Roque sisters, Claude and Arlette, who were in their late teens, camped overnight in Parsons Ravine during their menstrual cycle. Ruth Hiram, our librarian, grows old roses exclusively for their fragrance. Jane Morse often nursed her first child on a bench in the common.

If physical life was a powerful attractant, it was not the special property of the female population. Dry Falls is a prosperous farming community, the exception in Maine, teeming with life, surrounded by fields of feed corn and tender alfalfa, by pastures where mammals with distended udders are grazing, where circles of cow dung swarm with carrion insects. In the summer the farm hands work bare-chested, raising a sweat, bringing earth and manure indoors on the soles of their boots. We have chicken farms in the area, hens raised for eggs. Michel Roque breeds sheep and goats, and makes tangy cheeses from their milk. Evan McNeil's Highland Kennels is famous in New England for its Border collies, uncanny, intelligent herding dogs with a cast in one eye. Around here the life cycle operates at a sped-up pace. Something is always breeding in our vicinityÑsprouting, dropping, hatching, whelping, fermenting. The township of Dry Falls fairly reeks of generativity, more than enough to call forth the legions of the disembodied.

If bodiless entities are attracted by an abundance of life, there are those in our community who are drawn to the immaterial. Among our year-round inhabitants are a number who have retired or escaped from cities, and whose interests are far removed from agriculture. Some of these peaceable refugees started a discussion group, meeting at one another's houses as often as they could manage it. They kept the group and its purpose to themselves. If they had broadcast the fact that their topic was psychical research, who knows what kind of chowderheads and dabblers might have begged for admittance? No one in the group was a professional parapsychologist; but they were well informed on the subject, serious and skeptical. Walter Emmet had scholarly credentials in another field, eighteenth-century American furniture and decorative arts. Mary Grey Hodges was a registered nurse, formerly in practice in Bangor, who founded our Visiting Nurses Association. David Busch had been a staff photographer for Decade magazine, who went off on his own to specialize in nature and landscapes. Lorraine Conner Drago was a local real-estate agent, a mundane career for a person with clairvoyant abilities. At age fifty-one, my husband, Henry, was their youngest member.

When Henry joined up, I remember hoping that Bishop Hollins wouldn't get wind of it. Our Bishop was the crusading sort of clergyman, not much interested in the spiritual life, let alone in spirits. He thought the mission of the Church was people helping people, like the Community Chest, the March of Dimes, or the United Way. On one of his official parish visits he scolded Henry for holding too many meditation sessions, and ordered him to start a bimonthly meeting of Parents Without Partners. Henry's psychical research group did nothing to ease the pain of divorce or stop world hunger, but it seemed to me they had some concern with human betterment. When they met at the rectory in October of 1973Ñfour sober elderly people and my youthful husbandÑMary Grey read aloud a paper on healer-treated water. Mary Grey read too fast and dropped her voice at the end of every sentence, but the message and its implications were far-reaching. If one healer could purify a tank of contaminated water, a squadron of healers might be able to revive Lake Erie.

After the reading I provided light refreshments--coffee, cider, and date bars made with oatmeal. Walter wanted to conduct an experiment in extrasensory perception. "Not a very rigorous experiment," he said. "Just a little stricter than a parlor game." He brought in a folding screen from the dining room, and placed a side table behind it. Behind the screen he opened a satchel and placed an object from his private collection on top of the table. Walter himself did not know the identity of the object. He had asked someone else to select it and wrap it in several layers of heavy brown mailing paper. Walter gave us ten minutes by the clock to receive impressions and to write down any images that came to us, however fragmentary. I played along, so as not to disrupt the atmosphere, but my mind wandered out to the kitchen where the supper dishes were soaking in the sink and the macaroni and cheese was hardening in its casserole.

Ten minutes later, Walter called us to order. "Nothing," said David. "It couldn't have any relevance. I kept getting a name with a 'k' in it--Kennett? Or Mackenzie?" Lorraine read her notes out loud: "wavy glass," "the size of a julep cup," "bubbles," "black flecks," "tilting sideways." Mary Grey's paper was blank. "I kept dozing off," she apologized. "I pass," I told Walter, "I have about as much ESP as a tree stump." Walter turned to Henry, whose notepad was covered with writing. When Henry closed his eyes he had seen a circle of light, golden light, with a red glow at the apex of the circle. In a moment the circle developed a foot, or base. "Like a bowl," said Henry, "a yellow bowl, but I think it was metal."

Walter started unwrapping the object before Henry had finished, tearing at the paper, wrenching the bands of Scotch tape. He pulled out a little footed cup, four inches in diameter, hammered out of brass, burnished to a soft golden luster. "One of my prizes," said Walter, handing it to Henry. "This communion cup belonged to the first rector of King's Chapel in Boston. He took it with him to deathbeds, when he was called out to give the last rites." There was a round of applause for Henry. David clapped him on the shoulder. "A religious object," he said. "You had an unfair advantage, padre."

Henry's accomplishment called for a round of drinks. I took orders and poured out the liquor. Henry asked for a brandy. Lorraine seemed a little less animated than the others. She had once taken part in the ESP trials at Duke University, when the great J. B. Rhine had given her a high mark for accuracy. Walter salvaged her pride. "You got through," he said. "You scored a hit. You, too, David." He explained that the communion cup was displayed on a cabinet shelf next to a beaker, a hand-blown colonial drinking vessel dating from the 1760s. The name of the person who had selected the brass cup and wrapped it was Janet McKay, who did occasional secretarial chores for Walter.

The Uncanny was with us, a seventh presence in the room. I caught the group's excitement, a collective shiver. Henry's direct hit now seemed less dramatic than Lorraine's and David's oblique ones. A priest, after all, is supposed to be in touch with the invisible. I could see that their faces looked younger; years had dropped away. With his small, sharp features, Walter looked like a boy turned white early. Henry's face was so flushed and unguarded I was almost embarrassed for him. My own face, reflected in the mirror over the fireplace, looked as pretty as I get, with my bumpy nose, pale green eyes, pale hair, pale lashes and eyebrows. I looked like a piece of straw, but a fresh piece of straw before the weather starts to spoil it. I blessed Walter (who is actually a judgmental, self-centered little stickler) for bringing some spark to our lives just as winter was upon us.

At the time I believed no harm could come from these games, since their immediate effects were restorative and beneficial. I listened as they talked about agendas for the next month of meetings. I thought I might join them, if more of the sessions were like this one. It seemed their appetite for thrills had been slaked, at least for the present. In Henry's opinion, they were putting the cart before the horse, delving into parapsychology without more grounding in physiology and psychiatry. David suggested they read a new book on the two halves of the brain. Mary Grey offered to report on dissociation and multiple personalities. I decided not to join them after all, if they were going to be so studious. At least my husband had found a hobby, an interest outside his work. For some time I had wondered if his work were more burdensome than satisfying.

Incubus

- paperback: 336 pages

- Publisher: Ballantine Books

- ISBN-10: 0345438167

- ISBN-13: 9780345438164