Excerpt

Excerpt

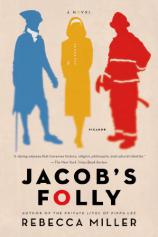

Jacob's Folly

1

I, the being in question, having spent nearly three hundred years lost as a pomegranate pip in a lake of aspic, amnesiac, bodiless, and comatose, a nugget of spirit but nothing else, found myself quickening, gaining form, weight, and, finally, consciousness. I did not remember dying, so my first thoughts were confused, and a little desperate.

As the blinding layer of black cloud I was enshrouded in dissipated, I saw the moon: opalescent, crater-pocked, impassive; frighteningly close. Indifferent stars carved up the firmament with their dazzling, ancient patterns. There was an echoing sound, like huge air bubbles escaping flatulently from an enormous wide-mouthed bottle underwater in a Turkish bath with a domed roof, but there was also a tearing—a continuous ripping, as if a universe-sized sheet of canvas were being torn asunder. I now know this was the fabric of time. I felt intensely alone and cried out, but my shriek sounded submerged. Instinctively, I beat the wings I didn’t know I had, and rose. I could fly! Was I dreaming? The black air was surprisingly viscous. My wings outstretched, I let myself descend, circling slowly through the thick stuff, passing through roiling, wispy clouds that felt cool on my skin. I was definitely awake. Could I be an angel? Euphoria and disbelief gathered in me. I reveled at having been chosen, against all odds, to be part of the heavenly host. I yearned to admire myself—or better, to be admired. I knew I must be very beautiful. I flapped my wings, spreading them wide, banking, making a slow round, wending my way down through the night. Below me, a web of lights, like a spume of stars, spilled out into a great darkness. As I neared, I saw the blackness churning, cresting: the sea. I was looking down on the earth! But what were all those lights?

Descending more rapidly as old rosy-fingers passed her bright hand over the ocean, washing it with light, I could now make out a crust of houses, built up on the twinkling island below like a skin malady. The massive grid of roofs rose to meet me vertiginously.

Swirling through the atmosphere, I had no idea where I was, but I knew I’d been gone a long time. Smooth-hipped, humpish carriages gleamed at the doors of the toylike dwellings; streetlamps spilled pools of steady light on ruled streets as smooth as stretched toffee: it was the future, I knew it. The last tool of illumination I had seen was a porcelain candelabrum beside my bed in Paris, in 1773. It was encrusted with light green leaves, tiny pink roses, and cherubim.

Still in the meat of my youth, I lay shivering with fever, my chest tight, sweat trickling down my sides. Now and then Solange would look in on me, the silk of her dress whispering as she moved about the room, replacing my water jug or plumping my pillow. Her gardenia perfume was too pungent for my strangled breath and I turned away as she leaned over me, yet I never took my eyes from the candelabrum. I found it a little garish—but what did I know? I was an ex-peddler, born in a tenement. I was lucky to even be next to this six-branched, delicately fluted masterpiece with twelve naked winged babies crawling over its glazed surface. Cascades of hardened beeswax spilled from each candle and all along the porcelain base, mingling with the cupids and tangling with the roses—the result of a week-long bacchanal, my meager staff too exhausted from entertaining the guests to scrape wax off candlesticks in the morning.

I watched, fascinated, my eyes dry, breath short, as each drip was formed: at the base of the flame, a little pool of molten wax glistened, plump as a tear on the rim of a woman’s eye; when the pool grew too great, it breached the worn edge of the candle, trickling freely along the shaft and finding its crooked path down the petrified waterfall. Moving farther and farther away from the source of heat, the cooling wax became hesitant, cloudy, until it froze entirely, fusing itself to the spillage.

I stared at the wax dripping down the candles for hours and hours, until, at dawn, I died. Sunday, the seventh of February, 1773. I was thirty-one. After that, nothing. And now I was an angel! I imagined myself as a fully formed Christian seraph, a Viking with blond hair, a beautiful chiseled torso, hairless feet, and eyes the color of whiskey. When I was alive, I was dark haired, short, slight, with light eyes, strong teeth, and a thick, long sex that I scented and coiled inside my britches daily with great care and pride, an aspect of my physicality which I hoped had been duplicated by the Almighty; but whenever I tried to look down at myself I could not move my neck, and my arms felt very weak. I assumed this stiffness was due to the long period of being dead.

Something amazing had happened to my sight: it was as if the top of my head had been removed and replaced with an enormous eye. I could see jagged purple clouds drifting above me, the streets stretching away at either side, and the houses below. This is how angels see, I marveled.

I noticed a gigantic figure stride out of one of the shiny carriages. Trying to focus on him and ignore the rest of the nearly 360-degree view, I descended cautiously, not yet in full command of my wings, afraid that the man might see me, yet half hoping he would. The thought of bringing this Titan to his knees with astonishment and awe was attractive to me. I imagined myself as an angel in a painting, my chiton frozen mid-billow as I reached my delicate hands out expressively, the object of my communication falling to the ground with awe and wonder, his eyes rolling up in his head.

Yet, as I hovered above him, I had an alarming double vision: I saw the man, and I knew him.

Jacob's Folly

- Genres: Fiction, Historical Fiction

- paperback: 384 pages

- Publisher: Picador

- ISBN-10: 1250043603

- ISBN-13: 9781250043603