I have heard writers insist, when asked about the truths that inspired their work, that there are no truths, that they "made it all up." Before my own collection of stories became a book that newspaper reporters and old friends and family from back home could read, I failed to understand this response. Made it all up? You didn't imagine any of the scenes set on the city streets you walked as a teenager? You never read a newspaper article and got an idea? You never experienced any of the acts --- arguing, lovemaking --- that you write about with so much authority? Do you live your life only in front of the computer, writing and doing research on the internet? Could it all really be invention?

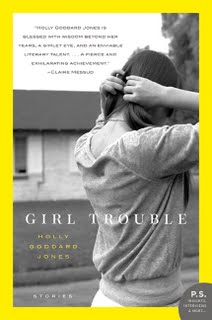

I have heard writers insist, when asked about the truths that inspired their work, that there are no truths, that they "made it all up." Before my own collection of stories became a book that newspaper reporters and old friends and family from back home could read, I failed to understand this response. Made it all up? You didn't imagine any of the scenes set on the city streets you walked as a teenager? You never read a newspaper article and got an idea? You never experienced any of the acts --- arguing, lovemaking --- that you write about with so much authority? Do you live your life only in front of the computer, writing and doing research on the internet? Could it all really be invention?Of course not. No writer can claim all of that. But I understand now the temptation to try as I field questions about how much of my book is "actually true." Call me naïve, and you'd be right. I wrote a book of stories set in a small, western Kentucky town, and though I'm from a small, western Kentucky town, it had barely occurred to me that readers might want to take the book's stories literally, or semi-literally. Residents of Russellville, Kentucky, will recognize my fictional Roma's local barbecue joint, its Tobacco Festival, its town square with a Civil War soldier stationed proudly in the center. Is it unreasonable, then, for them to wonder if the high school basketball coach who got his star player pregnant might also be real, or sort of real? (He's not.) Should my loved ones be faulted for seeing themselves in the mothers and fathers and best friends who people this familiar landscape? No --- but it would be a mistake to. The Empire State Building really exists, but there was never a King Kong to climb it.

The place in the book where I draw most evidently from the biography of a loved one is in the story "Allegory of a Cave," which is about a middle school boy who was born with juvenile cataracts --- a condition that forces him to wear thick glasses, take eye drops twice daily, and brings with it the looming threat of eventual glaucoma. My little brother, Eric, was born with this condition, and the first draft of the story (which was radically different from the one appearing in Girl Trouble) was propelled for me by a what-if question: What if the threat of glaucoma were more serious for Eric than it appears to be, and he had to spend his adolescence bracing himself for blindness? From there, the plot developed around a series of lesser what-ifs. I wondered what Eric would do about his medicine, which my father always administered and which required refrigeration, if he wanted to go to summer camp. Then, I wondered what would happen if this shared ritual --- the intimacy of a parent leaning in to give a child medicine ---ceased. Would the child miss it? Would he be relieved?

You can see that, in my reconstructing of the story's conception, I shifted from identifying the boy as "Eric" to identifying him as "the child." The writing process, for me, often starts this way with some detail or idea from real life --- though usually that process of borrowing is much subtler than the scenario I've just outlined --- and the more I work through the what-ifs, the themes, and images, the more I'm trading the world I know for the one I've invented. And though the story was rooted for me initially in the question of intimacy between fathers and sons --- about what happens when you lose ritual as a pretense for that intimacy --- the revision had much more to say about Ben's relationship with his mother: the Oedipal triangle between Ben and his parents, an allusion that locked into place for me perfectly when I realized that I'd already been playing with the tragedy's imagery of light and dark, blindness and sight. That was accidental and delightful; I stumbled into it, and the stumbling took me farther than ever before away from the story's grain of fact.

For most fiction writers, the little details from life are ways of hypnotizing ourselves into those imaginative leaps that make the writing process so exciting. Sometimes the truths can be significant, like my brother's eye disease. But often they're trifling, merely decorative. At one point in "Allegory of a Cave," for instance, Ben remembers going to his father after falling from his bike, only to be told, teasingly, to "Cry me a handful." It's a harsh moment, and it helps to illustrate the father's tendency to handle difficult situations with irreverence and spite, as a kind of defensive posturing.

My father often said to me "Cry me a handful" when I was small. He did it, though, in an entirely different spirit --- not as a response to real pain but to those situations when I'd thrown a hissy fit out of pure selfishness: when I was denied some toy or candy bar I wanted, or when I'd argued with my brother and demanded my way. In that context, it was actually a kind of brilliant, even gentle retort: one that surprised me into silence, teaching me that I'd be treated with seriousness and respect when I could articulate my frustrations with seriousness and respect. His comportment in saying "Cry me a handful" was warm, his lips pulled into a smile that forgave rather than mocked. My memories of that line are good ones. So why did I twist it into an act of cruelty in "Allegory of a Cave"? Simply because it was convenient, and most writers are unrepentant opportunists.

---Holly Goddard Jones