Matthew is also the author of The Dante Club and The Poe Shadow.

Today book publishing is tagged as "old media." It sticks to tradition. The industry, like most, has had its financial setbacks, including the dominant bookstore chains, and may be contracting. It has struggled to find a way to profitably interface with digital and download technologies.

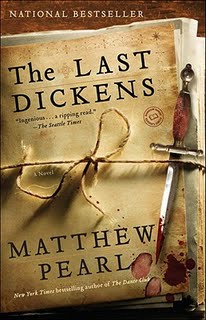

Today book publishing is tagged as "old media." It sticks to tradition. The industry, like most, has had its financial setbacks, including the dominant bookstore chains, and may be contracting. It has struggled to find a way to profitably interface with digital and download technologies.I was excited that in my latest novel, The Last Dickens, I was able to return to a time when book publishing was not just cutting edge. It was an adventure. In my story, the hero is a young publisher named James Osgood. When he finds out that Dickens has died without turning in the second half of his last novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, Osgood sets off on a dangerous quest to discover the missing pages. Osgood was an actual person, and we've even had him "interview" me for a special feature in the paperback of The Last Dickens.

In the nineteenth century, the industry was still young. Trade journals and magazines were just beginning and were allowing industry insiders learn about each other. It had not been very long that the bookstores and publishers had split into separate entities. The professionalization of authors was also recent, so that by the mid century distinct interests had emerged: publishers, booksellers and authors.

Books were as powerful as ever. Along with the growth in newspapers, they constituted the primary form of spreading information and entertainment.

In the 1830s, a fictional manuscript circulated before its publication detailing how a Catholic convent kidnapped and held Protestant girls against their wills. A riot occurred at a convent outside of Boston, where fires were set and lives threatened.

Meanwhile, copyright law at the time did not protect any foreign authors. That meant American publishers could print and reprint foreign authors like Charles Dickens without paying them a dime.

This created a volatile situation. Sort of a literary black hole, where priceless properties were up for grabs. Since you could not purchase reliable rights to publish a foreign author, the value was not in who could secure rights (as it is today), but in who could get a hold of a book and publish it *first*.

It was all about timing, and the black market could yield a fortune.

There are moments when doing research when finding a small detail fires your imagination and opens an unexpected window into the past. This time, it was the discovery that the publishing firms would hire covert agents who waited at the ports and harbors of the major American cities waiting for valuable manuscripts to come in. Particularly Dickens. There was at least one specific report of a manuscript successfully pilfered.

I couldn't stop imagining who these literary bounty hunters might be. What were their backgrounds? What techniques did they employ? Were there rivalries?

I wanted to find more. But like much of history, nothing more than a few lines-worth of material had been documented. This isn't surprising, as these were sketchy tactics being used by self-consciously sketchy publishers.

That's where historical fiction can expand on a world that locks out nonfiction. For The Last Dickens, I created a world and avocation for these Bookaneers (as they're known in my book). They were daring literary pirates willing to use almost any tactic to obtain their treasures. These Bookaneers get tangled in the same adventure that Osgood finds himself, battling secret forces to find the ending of Dickens's final novel. I hope I'll have the chance to use the characters of the Bookaneers in future books, too.

Who would have thought publishing history could be so fun?

---Matthew Pearl