In a happy period of my mid-life I happened to live more than two years in the USA, to be precise, in Connecticut. That was in the late '80s. I was a Fulbright fellow, but actually, I was a prince in the clothes of a beggar. At the time I was thirty-nine, the author of three novels and twelve other books. All of them written and published in Hungarian. I tried everything to make my name well-known in the USA. I published a story in The New York Times. They misspelled my name (Milos Vamos). I fought even harder. I wanted to find a big publisher for my novels. I had three agents, one after the other, including one of the nicest men in New York City, Robert Lantz. Unfortunately, he was also one of the busiest men in the City, and he devoted most of his time to his more famous clients like Peter Shaffer and Miloš Forman. I happened to be one of the most impatient men --- and I dumped all my U.S. agents by and by.

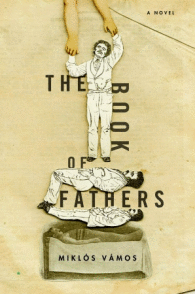

In a happy period of my mid-life I happened to live more than two years in the USA, to be precise, in Connecticut. That was in the late '80s. I was a Fulbright fellow, but actually, I was a prince in the clothes of a beggar. At the time I was thirty-nine, the author of three novels and twelve other books. All of them written and published in Hungarian. I tried everything to make my name well-known in the USA. I published a story in The New York Times. They misspelled my name (Milos Vamos). I fought even harder. I wanted to find a big publisher for my novels. I had three agents, one after the other, including one of the nicest men in New York City, Robert Lantz. Unfortunately, he was also one of the busiest men in the City, and he devoted most of his time to his more famous clients like Peter Shaffer and Miloš Forman. I happened to be one of the most impatient men --- and I dumped all my U.S. agents by and by.One of my novels was almost accepted by Scribner. Then, they dumped me. I had to realize that the U.S. world of publishing would not wait for me, and my works. I came home to my native Hungary. Wrote some more novels and other books, including The Book of Fathers, which is probably the best I have ever done. It came out in Hungary in 2000, and I considered it as my farewell to the twentieth century.

And what happened? A German publisher (Random House btb) brought it out. It became a bestseller. Afterward, Susanna Lea, one of the nicest women in Paris and New York City, decided to represent me throughout the world. Ever since then, every year I receive three to four contacts from different publishers of different countries. Now the time has come, and one of my books appears in the USA from Other Press. Every novel has its fate, and in each story of publishing there are also happy endings. Now all I need is some good luck from the readers. Do I deserve it? That has no importance in matters of luck.

I need some love from those readers for whom "Europe" sounds like the name of the weird banknotes used on the other side of the ocean, and who cannot tell the name of the Hungarian capital (Bucharest? Budapest? Budabest?).

When Europeans --- especially East Europeans, more especially Hungarians --- give each other a friendly kiss, they always kiss both cheeks. Americans only one. When a Hungarian (let's say, a male) comes to the United States, he kisses somebody's, anybody's, left cheek, then he moves to the right cheek. The American woman doesn't know what the hell is going on. She draws back. Then she understands that this was a second kiss, and she wants to return it. But it's already too late. Sometimes the heads bump against each other, and the whole scene becomes somewhat embarrassing. Americans tend to misunderstand this second kiss, believing it is something more than just a friendly gesture. They are surprised or puzzled.

Hungarians are willing to adopt the American traditions. When in Philadelphia, do as the Phillies do. Sooner or later they adjust to the single kiss. But, again, it's too late. Almost every American friend has already accepted the habit of the double kiss. He or she waits patiently for the second kiss, but it isn't offered. Sometimes the American moves toward the Hungarian's other cheek, but now it's the Hungarian's turn to be late. By the time he goes for the second kiss, the American has already retreated. More accidents are possible --- bumped noses, tangled hair, etc. The embarrassment is still there.

Everyone knows that in any exchange of kisses there is always the potential for misunderstanding. So when Hungarians and Americans kiss --- a greeting that stretches across oceans and cultures and language and time --- it comes as no surprise that such kisses can be an awkward reach across a junk pile of differences.

I would be so satisfied if my book could give an occasion to celebrate those clumsy yet warm meetings between Americans and Hungarians. The history of these two nations and its peoples is totally different. Still, both are crammed with the vagaries of political leadership, the irreversible pomposities of awful translations and, of course, the usual absurdities of life itself. But, there are also the common experiences of literature, of everyday laughter and tears made real by language and story and the fire of imagination. If occasionally we bump noses in the exchange of greetings and understanding, let us still enjoy our closeness and let us blame any embarrassment on history. Language, after all, has its limitations. Kisses, on the other hand, well ... kisses are kisses, they need no translation.

---Miklós Vámos