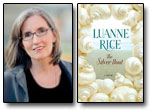

A New York Times bestseller whose work has been internationally acclaimed, Luanne Rice is the author of 29 novels --- the latest of which, THE SILVER BOAT, is now available in bookstores. Below she remembers the woman who helped launch her writing career by giving her what she never had herself --- a sense of freedom.

On summer mornings when I was young, my mother held writing workshops for my sisters and me at our summer cottage. We sat the oak table, windows open wide, and she said, “Write about what you hear.” Sounds drifted in: oak leaves rustling, waves hitting the shore, the joyous shrieks of our friends playing on the beach.

On summer mornings when I was young, my mother held writing workshops for my sisters and me at our summer cottage. We sat the oak table, windows open wide, and she said, “Write about what you hear.” Sounds drifted in: oak leaves rustling, waves hitting the shore, the joyous shrieks of our friends playing on the beach.

My mother, Lucille Arrigan Rice, had returned to school to get her Masters in Education, and we were her guinea pigs. Although I begged to be set free, I found myself writing about the sounds, letting them guide me into stories.

Those days taught me to sit still, to write every day, to observe nature and life. Our family was full of secrets and complicated, tragic love. Through writing fiction, my characters have helped me understand.

My mother finished grad school and became an English teacher. In college, she had written plays, had one produced and performed in Boston.

She married my father right after he returned from World War II. She was beautiful, he was handsome; they came from similar working-class backgrounds, had met at the beach, and had a romantic love story. It took nine years for them to have their first child, me. Passion, and the belief things would get better, must have kept her with him, because life was not easy.

My father kept us in suspended animation, always guessing. Would he come home that night? I developed detective skills; by the time I was seven, I knew he drank and had affairs, and that she was in a state of perpetual heartbreak.

My grandmother lived with us, a sort of second mother. My mother would read us Dickens, Shakespeare, Dylan Thomas, American plays of the 1930s; she encouraged us to memorize poems, and write our own; each Saturday she took us downtown to the library and art museum.

When it came to art and literature, she was wonderful. Emotionally, she was numb, and left my sisters and me to mother each other. Our grandmother, Mim, took care of the basics, like cooking our meals, mending our clothes, and rocking us on her lap when we had chicken pox.

My sisters and I shared a bedroom. After we were in bed, my mother wrote at the dining table. The sound of her typewriter was my lullaby. Yet she never published again, and when she died, her desk contained many unfinished short stories.

I often feel my mother’s influence. Many of my characters are artists, and that comes from her --- our museum visits and the fact that she painted, on a tall easel set up in the kitchen. She taught me to care deeply about the planet and all who inhabit it, to listen to wind in the trees, to watch clouds in the sky.

The year she retired, ready to write a novel, she developed a brain tumor. Her next nine years were a long, terrible decline, but she never complained. She used her experience as material, and wrote in notebooks. I watched her lose her ability to walk, live on her own, and hold her head up. But she wrote, in a spidery scrawl, until the very end.

When I began to be published, I would show her my manuscript, the galleys --- long sheets of newsprint back then --- jacket sketches, author photos and the finished book. She seemed happy and proud.

“Promise me you’ll never worry what I’ll think,” she told me once. “Just write.” My life is my material, and she was letting me know I had her blessing to use it.

My first novel, ANGELS ALL OVER TOWN, opens with Una, the main character and the oldest of three sisters, sitting on the toilet while, just outside the bathroom door, her father’s drunken ghost rants that no man will ever be good enough for her.

Three of my aunts disowned me for that novel. When I read at my hometown library, a former neighbor yelled from the back row that he was glad my father was dead so he didn’t have to know I’d written such garbage. Brendan Gill, The New Yorker drama critic and my mentor, told me not to worry about it; they’d take me back if I ever became well known.

His words didn’t soothe me. My mother’s did. “You didn’t worry what anyone would think, and you wrote a beautiful book,” she said. I’ll never forget the sense of freedom, comfort and love I felt in that moment.