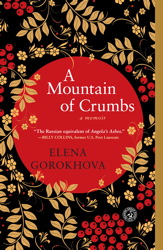

Elena Gorokhova is the author of the breathtaking memoir A MOUNTAIN OF CRUMBS, one of The Christian Science Monitor’s “10 Best Mother’s Day Books of 2010,” which is now available in paperback. Today, she shares the incredible story of her award-winning mother, who has dedicated her life to the service of others.

Photo: Elena and her mother.

I thought that A MOUNTAIN OF CRUMBS, my memoir about growing up in Soviet Russia, was my memoir. I didn’t know that it was my mother who would become the center of the story. My mother, a mirror image of my Motherland: overbearing, protective, difficult to leave. She was a survivor of the famine, Stalin’s terror and the Great Patriotic War, as WWII is known in Russia, and she controlled and protected ferociously. What had happened to her was not going to happen to us.

I thought that A MOUNTAIN OF CRUMBS, my memoir about growing up in Soviet Russia, was my memoir. I didn’t know that it was my mother who would become the center of the story. My mother, a mirror image of my Motherland: overbearing, protective, difficult to leave. She was a survivor of the famine, Stalin’s terror and the Great Patriotic War, as WWII is known in Russia, and she controlled and protected ferociously. What had happened to her was not going to happen to us. Almost 70 years ago, in the spring of 1942, a woman carried an unconscious nine-year-old boy into the make-shift hospital where my mother was a surgeon, one kilometer away from the front. It was April, and when the ice on the Volga turned porous and frail, mines frozen into the river began to explode, touched off by the slightest shift, sending flocks of birds into the air and schools of fish to the water’s surface, belly up. Locals with buckets, driven by wartime hunger, waded into the river to collect the unexpected harvest floating among the chunks of ice, setting off more mines.

It was prohibited to treat civilians in a military hospital, but my mother unbuttoned the boy’s quilted jacket and muddy pants and carefully pulled them away from his perforated flesh, revealing blind belly wounds: entrances of shells with no exists. She lifted a scalpel out of the boiling water, made an incision, and pulled apart flaps of skin, exposing multiple intestinal wounds, big and tiny holes in the coils of the boy’s belly. Then she removed each piece of shrapnel, rinsed the boy’s intestines with antiseptic, and sewed up the holes, one by one.

Every day of the war, the soldiers came in trucks from the front, and although she scooped the lice out of their wounds with a teacup and cleaned the flaps of torn tissue as diligently as she could, lice festered in layers of dirty bandages, keeping the wounded awake and screaming throughout the night. They were younger than she was, those wounded boys --- her brother’s age --- and she peered into their dusty faces, clinging to a shred of hope that, in some miraculous way, her brother, who was stationed on the Polish border when German tanks crossed into Russia on June 22, 1941, would be brought into her hospital for her to heal. She hoped her brother was not among the thousands of bodies she knew had been plowed into the warm summer earth of western Russia. She hoped for a quick victory in the Great Patriotic War.

Every day of the war, the soldiers came in trucks from the front, and although she scooped the lice out of their wounds with a teacup and cleaned the flaps of torn tissue as diligently as she could, lice festered in layers of dirty bandages, keeping the wounded awake and screaming throughout the night. They were younger than she was, those wounded boys --- her brother’s age --- and she peered into their dusty faces, clinging to a shred of hope that, in some miraculous way, her brother, who was stationed on the Polish border when German tanks crossed into Russia on June 22, 1941, would be brought into her hospital for her to heal. She hoped her brother was not among the thousands of bodies she knew had been plowed into the warm summer earth of western Russia. She hoped for a quick victory in the Great Patriotic War. Her brother never came home, and the Victory took five long, excruciating years.

May 9th is the anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany, a holiday that is visceral to every Russian. Last spring, a FedEx package from the Russian Consulate in New York addressed to my mother arrived at my house in New Jersey, where she has been living with me for 22 years. In it was a letter from the Consul to all living veterans of the Great Patriotic War, a certificate issued in my mother’s name, and a medal. It was her third medal: She received her first one for her valor during the war, and her second on the 50th anniversary of the Victory. This year, we will celebrate Victory Day on Sunday, May 8th. My mother will put on her best dress, pin her medals to her chest, and offer to help me make pirozhki for our celebration, as we did last year. We will roll the dough and chop eggs and scallions side by side in our kitchen.

Here in America, it will also be Mother’s Day.