In her debut novel, 22 BRITANNIA ROAD, Amanda Hodgkinson delivers a tale of a family desperate to put itself back together after WWII forces them apart. Below, Amanda speaks about her own father; a father who preferred to do rather than to read, but who still instilled in Amanda the desire to take risks and become a writer.

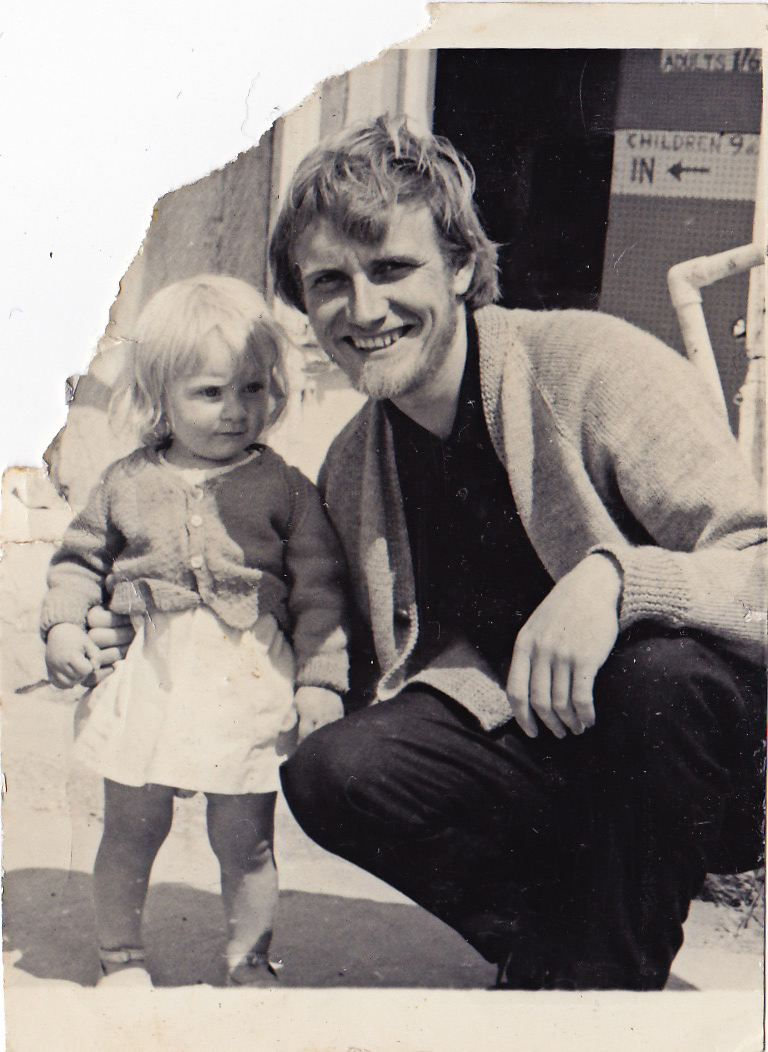

Photo: young Amanda and her father.

My father has never been a great reader. He has always liked doing things, not reading about other people doing things. Growing up, I remember him as a talented builder, a carpenter, potter, and an artist. He was big-hearted, a hopeful dreamer, an impatient schemer. A man full of wild, ambitious plans. A man who probably believed he could turn back tides if he ever put his mind to it.

As I child I loved to watch him work. When he re-roofed our house, it was quite natural for me to shoot up the ladder behind him and sit, aged eight, astride the roof apex, handing him tiles, the world very far below and no rope or safety harness to hold me. Actually, this memory alarms me slightly now. I can’t even imagine my own daughters climbing on high rooftops at that age. . .

My father wanted a daughter who was brave, a Calamity Jane of a girl. I was determined to be that girl. A girl who thought nothing of leaping onto the back of the wild-eyed, unbroken gypsy pony he bought for me, clinging on for dear life, galloping it along the seawall and riding it bareback into the sea, my father yelling encouragements from the shore.

I think my father would have loved to have been a 19th century pioneer, a man who had to build his own log cabin in the wilderness and protect his family from wild bears and marauders. As it was, he began his working life as a high school art teacher in the early 1970s, a hippie who had to wear a shirt and tie to work. A man with four children to support and a gentle, shy wife who often spoke of having even more kids.

When we had all left home and he had grown older, my father became a little deaf. He still does not admit this and is defiantly young at heart. Today he is a wiry, muscular old man, still restless and unlikely to be found sitting around. When he suffered a mild heart attack a few years ago, the one thing he worried about, lying in his hospital bed complaining in melodramatic tones to my mother, was that he had never been white water rafting. . .

Writing this, I called my dad to talk to him about my writing career. To ask if he had ever imagined I would become a novelist.

When I phone my parents, I always speak to my mother. My father, still without a hearing aid, doesn’t like the phone. And yet, he stands beside my mother, talking incessantly. A call to them means a long time listening patiently to his excited, slightly raised voice in the background and then to my mother repeating what he just said to her, to say to me. This time I asked Mum to put him on the phone.

“You changed when you were a teenager,” he said. “You spent all your time reading.”

I heard a note of regret in his voice. As if books, and not just adolescence, had taken his doting daughter away from him and replaced her with a suddenly studious young woman.

There is a silence. I repeat the question, a little louder, wondering whether I ought to just ask my mother.

“You always had such a rich imagination,” he replies. “You were such a dreamer.”

There is another small silence. Then he says, “I am so bloody proud of you,” and

I hear a faint wobble of emotion in his voice.

He hands the phone back to my mother and I hear him telling her, to tell me, he is reading my novel (only a few pages in) and thinks it’s great. Then he is gone, off to do something else.

“Something important, no doubt,” my mother says, and laughs.

Happy Father’s day, Dad. And thank you. Not for introducing me to books and literature, but for showing me how to dream and take risks. Two things every writer needs to be able to do.