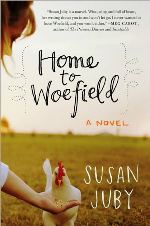

Susan Juby is the author of Home to Woefield, a charming novel of a young woman determined to remake her family's farm. In this essay, Susan shares her memories of the inspiring, yet intimidating English teacher whose impact set her on a path to writing. Check back tomorrow for Part II. Click here to enter to win a copy of Home to Woefield. Visit www.SusanJuby.com for more.

My friends and I were not exactly the academic elite. We hung out in the smoking area; our boyfriends drove large trucks and loud cars and hadn’t appeared in any graduating class photos. We had permed, feathered hair and a strong preference for black eyeliner and clothing with extra zippers. When we weren’t sleeping during class, we were talking. As one of the leading troublemakers in my set, I’d started my career as a problem student when I got suspended for the first time in Grade 8. That time it was for smoking. After that I got into trouble for an ever-escalating scale of offences.

In spite of all that, Mr. Law seemed to have time for me. He was one of the only teachers who did. I’m not suggesting he was like that principal who cleaned up the halls of his school using tough love and a large stick. If that were the case, I’d have been one of the first out the door. Nor was Mr. Law one of those To Sir with Love types. A serious man with a rarely seen ironic smile, he was considered a hard case by most of the students.

Maybe the reason he had a bit more tolerance for me than did the other teachers was that we shared an enthusiasm for reading. I read everything on the assigned reading list in the first month of school and, unlike most of my classmates, I actually loved the books chosen. And I liked talking about them in class, even though my comments were less than penetrating.

“Can anyone tell me the theme of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four?” he’d ask.

Deafening silence into which I raised my hand.

“Yes, Susan?”

“It’s like the whole world becomes like school. It’s a drag. Like you can’t get any privacy. Total fascism, man.”

“Hmmm, yes. I see your point.”

The difference between Mr. Law and the rest of the teachers is that he actually called on me when I raised my hand. No one else would have dared.

Our agreement on the general excellence of books didn’t mean I was producing top-notch work or anything. I wasn’t scoring straight “A”s in English, belying my otherwise abysmal performance in school. No sir.

Any hopes Mr. Law had that my interest in the class readings would translate into academic success were dashed as I produced mostly mediocre papers. But Mr. Law didn’t give up or treat me like the “C” student I so obviously was. And even though I wasn’t about to show it, that meant a lot to me because, as my high school years progressed and I continued what my favorite musical artist at that time, Ozzy Osbourne, would have called my journey “off the rails on a crazy train”, any confidence I’d gained from being a good student in elementary school disappeared.

Grade 11 was the turning point. Would I make it to Grade 12 and graduate? Or would I, like many of my friends, simply fade out of school? In my crowd, there was never any big announcement about quitting. My friends just simply… stopped… going. Dropping out was a process that started in Grade 8 and, for many of us, finished in Grade 11.

There was one group in our school who were absolutely certain to graduate. They were the kids who took a program called Directed Studies, which was developed and run by Mr. Law. Directed Studies was designed to allow the gifted students to explore their many and varied talents; it allowed the smartest kids in the school to mingle with other similarly gifted young people (as though they didn’t already huddle together like the last survivors of some anti-intellectual rebellion.) Anyway, in Directed Studies, or DS, as it was known, students got to choose a field of study and develop their own curricula. They went on retreats to discuss the trials and tribulations of being brilliant: “It’s gotten to the stage where particle physics (neuroscience, nanotechnology etc.) simply isn’t enough of a challenge for me anymore” or “I am so smart it’s actually sort of painful.” At the end of every year they gave a public presentation to show the school and larger community what they’d learned.

The Directed Studies program wasn’t something I spent any time thinking about. It was like the chess club, reserved for academic achievers, the intellectual “haves and have mores”, as Mr. Bush might put it.

So when Mr. Law came up to me after class one day and asked if I was interested in taking DS my jaw nearly hit the floor. Me! In Directed Studies! With all the chess club people! Surely he meant Detention, Special. No, he assured me, he actually meant Directed Studies.

My first instinct was to say no. After all, particle physics was not my bag. My math studies had stalled somewhere around Grade 9. (To this day I require one of those tip calculators when I go to a restaurant: Let this be a warning to all those young people who don’t feel math is important.)

“What would I do?” I asked him.

“Well, what are you interested in?” I’m sure part of him must have been worried I was going to propose a course in dating minor drug dealers. But I didn’t. I was too astonished by his question.